Although I was in no danger on the east side of the park, when I share the photos I took at Logan Pass, you’ll see that the post title isn’t entirely hyperbole. Among the last things I did yesterday was book a bus tour because given the state of the park, this seemed a better option than attempting a self-guided exploration. The tour was scheduled for an 08:00 pickup and I’m an early riser so I had time to have a cup of tea, fill my water bottle and slip a small bag of nuts and a protein bar in one of my travel vest’s many pockets before our guide arrived. I saw Chris and Wendy in the lobby and we renewed our acquaintance. Just before boarding the bus, I took this photo.

Since our driver Charles arrived on time, it’s about 08:00 and the camera is pointed directly at the sun. Clearly, for yet another day, Montana would fall far short of its Big Sky nickname and cling to what I’d dubbed – Big Ash Country.

Since our driver Charles arrived on time, it’s about 08:00 and the camera is pointed directly at the sun. Clearly, for yet another day, Montana would fall far short of its Big Sky nickname and cling to what I’d dubbed – Big Ash Country.

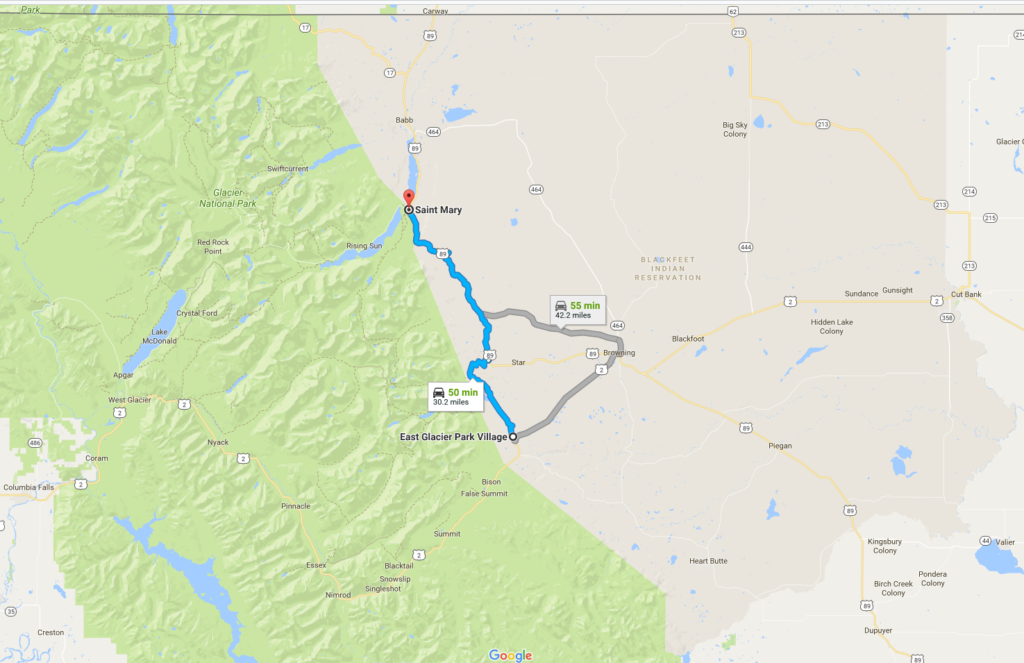

Glacier Park Lodge is a bit outside the park so to reach there we had to drive through a portion of the Blackfeet Reservation to our entrance point at St. Mary. We picked up a few other passengers at stops along the way – most memorably Stephanie V. the newly appointed Director of Tourism, Parks and Recreation for the Blackfeet Nation who had a small grant to explore ways for the reservation to attract more tourists. The St. Mary Entrance is the eastern terminus of the famous Going to the Sun Road making it an ideal starting point.

As shown by the signs in the two photos below, for those of us on this tour, the road would have been better named Going Through the Ash

Toward the Wildfire Road.

(I cropped the map above to highlight a few elements. First {and least important}, you can enlarge the map to clearly see the route I drove along Route 2 yesterday from Columbia Falls to East Glacier Park Village. Second, I wanted to highlight the route north because, despite its relative brevity, we passed an important place that some hope marks a new era for the Blackfeet people. Finally, given some of the discussion that will ensue, I think it’s important to highlight the area of the reservation which appears as the darker tan.)

The new era I mentioned began just more than a year before my trip – 4 April 2016 to be precise. It was on this day that a truck delivered 88 bison from Elk Island National Park in Alberta to the former AMC Ranch now renamed Buffalo Calf Winter Camp by Chief Earl Old Person. In an interview with the Missoulian, Chief Old Person said, “The Buffalo was our way of life. To bring the buffalo back here, we’re hoping they can help guide and lead our young people. We can look back and see and hear how the buffalo meant everything to our people.”

The Blackfeet Nation has sometimes been called the “Buffalo People” and, according to the website blackfeetcountry.com,

Buffalo were the main staple for the Blackfeet Indians. This animal provided food, clothing and shelter. The Blackfeet were nomadic people following the buffalo, luring them to the edge of a large cut-bank, driving them over the edge into a valley below of their death. Butchering was done immediately, the hides prepared by tanning.

All parts of the animal were utilized. The meat for food, the hide for lodges and clothing, bones for weapons and utensils, hoofs for glue, hair for decorations, and sinew for sewing. Internal parts were eaten as a delicacy, brains for tanning, and the head for religious purposes.

One of the saddest chapters of history for the Blackfeet Indians was the extermination of the buffalo. It was completely destroyed their lifestyle. With a climatic starvation winter in the year 1883-84, the Blackfeet lost one-third of the population.

Thus, although he passes it every day, it’s understandable why our guide Charles’s voice cracked with emotion when he pulled our bus to the side of the road as we drove past this particular herd of iniwa – the Blackfoot word for bison.

Mountains, rocks and glaciers

In an early post about this trip I engaged in a lengthy lecture about the Laramide orogeny, distinguishing between different types of mountains and the rocks of the Canadian Rockies. Now, I’ll provide a (relatively) brief look at some of the differences between what I saw in Banff NP and what I might have seen in Glacier NP.

Two mountain ranges, the Livingston and the more easterly Lewis Range trend from northwest to southeast (There’s that north to south bias again.) through Glacier. The park’s rocks, mountains, and valleys within the park were shaped over approximately 1.6 billion years of the Earth’s history by the same geologic processes (sediment deposition, uplift and thrust, faulting, and erosion) with which you should have some familiarity if you’ve followed me along both western trips. Glaciation is another force has shaped the park we visit (but won’t see well) today. This photo, taken at the St. Mary Visitor Center, gives some idea of what we’ll face as we ascend the road and travel west.

(If I’d wanted a tour of the Smokies, I could have gone to North Carolina or Tennessee and stayed considerably closer to home!)

Mountains and Rocks

Between 60 and 70 million years ago, uplift pushed up a slab of rock several miles thick that then slid east some 50 miles over much younger rock creating a nonconformity (a term you doubtless recall from this post). The Lewis Thrust Fault is major evidence of the tectonic events that created the mountains of Glacier NP. (Thrust faults place the area around them under horizontal compressive stresses causing shortening of the Earth’s crust. They typically dip at low angles, between about 10-40 degrees and most of these faults, as is the case in Glacier NP, place older rocks over younger rocks.) However, numerous other tectonic events were occurring simultaneously in and around the area; synclinal folding and other types of faulting are also evident.

Most of the rocks forming the mountains of Glacier NP are sedimentary rocks deposited more than 1.6 billion years ago by the Belt Sea that covered most of present day eastern Washington, northern Idaho, western Montana, and parts of Canada as well. The accumulation of sediments combined with heat, pressure, and time to create the park’s predominant layers of quartzite, siltite, argillite, limestone, and dolomite.

Glaciers

Let’s make a glacier (a moving ice sheet). Start with mountainous snow fields that follow repeated cycles when winter snowfall exceeds summer melting. Through the alternating freeze and thaw process, the snow becomes granular ice. Over time, ice layers build up, the ice recrystallizes, becomes denser, and eventually forms a massive sheet. Ice near the surface is often hard and brittle exerting pressure that makes the ice near the bottom of the sheet flexible. This generally happens when the ice is about 100 feet thick with a surface area of at least 25 acres. Depending on the amount of ice and the angle of the mountainside, gravity can start pulling the ice downhill. Once that movement starts, the ice sheet becomes a glacier.

Two major periods of glaciation, one ancient and one recent, also played a key factor in creating Glacier NP’s landscape. The Pleistocene Ice Age began about two million years ago and lasted nearly that long. Enormous ice sheets advanced and retreated across North America before melting more or less completely about 12,000 years ago. (It’s their action on the landscape, not the existence of the park’s remaining glaciers, that gave Glacier National Park its name.) In the periods when the ice advanced, so much of it filled the lower valleys that only the tops of the higher peaks would have been visible. When the ice retreated, it sculpted the mountains and valleys into a variety of landforms typical of alpine and valley glaciation filling the park with massive u-shaped valleys, numerous cirque lakes, horns, cols, moraines, and aretes.

The second period is largely responsible for the glaciers visible in the park today. They formed between 6,000 and 8,000 years ago and probably grew rapidly during the Little Ice Age that started in the sixteenth century and ended in the middle of the nineteenth when the glaciers began to slowly retreat.

Glacier National Park was established in 1910 and there were more than 150 glaciers within its boundaries. Today, only 39 named glaciers remain. However, a USGS survey revealed that between 1966 and 2015 the park’s named glaciers had retreated an average of 39 percent and 10 had lost more than half their ice over that half century. If the current rate of recession continues, it’s likely that by 2030 there won’t be any glaciers in Glacier National Park.