I’m going to start with this disclaimer: I will likely never know the full grandeur of the Grand Canyon. During my day and a half visit, I walked much of the 13-mile South Rim Trail and a short segment of the Bright Angel Trail that’s used by hikers and mule riders to descend to the canyon floor and, for those younger and more adventurous than I, to connect with the North Kaibab Trail as part of their journey between the south and north rims. That covers day one. On day two, I drove along Desert View Drive to some of the better-known viewpoints before heading off to Williams. With that, I’d guess I saw less than 10 percent of the canyon’s 277-mile length. I came nowhere near the North Rim nor did I visit the now famous Skywalk in the area known as Grand Canyon West. And it’s not likely I’ll return. So, I repeat, I will likely never know the full grandeur of the Grand Canyon.

A first (of several) early starts on this trip’s long days

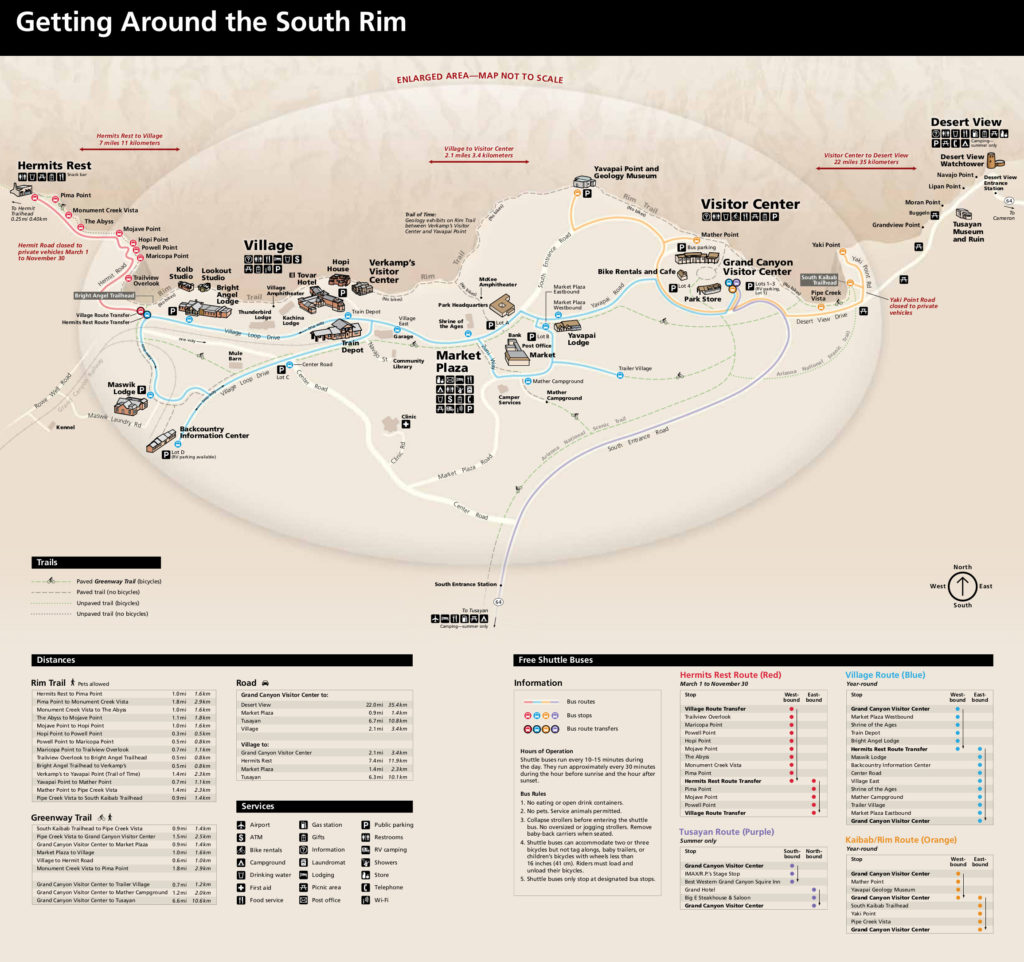

In the previous entry, I shared a few photos of my first views of the canyon itself. I took those in the area near the end of the path to the left of the Park Headquarters about halfway between Verkamp’s Visitor Center and Yavapi Point. (Enlarge the map by clicking on it.)

Thinking an early start would be beneficial both in terms of solitude and avoiding prolonged exposure to the heat of the day, I roused myself out of bed shortly after sunrise and trod the same path I had the previous night. (I didn’t get up to see the sun rise on the first morning but circumstances both practical and physical conspired to rouse me very early Saturday morning.)

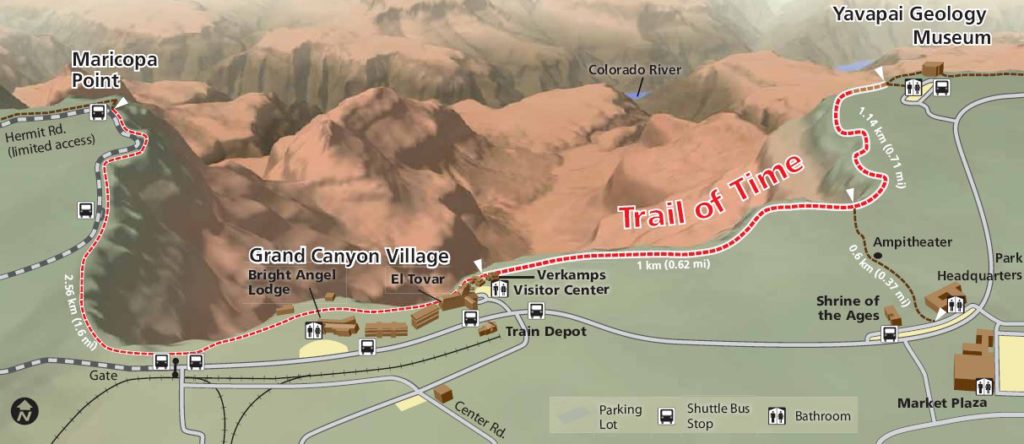

In 2010, the Park Service completed the installation of an interpretative timeline stretching about 2.8 miles from the Geology Museum at Yavapai Point to Maricopa Point along the South Rim Trail. The intent of the trail is to create a sense of the magnitude of geologic time while simultaneously exhibiting the rock types of the canyon and providing explanations of how the canyon formed.

I joined the trail at spot marked by the arrow at the end of the path between the Park Headquarters and the Shrine of the Ages on the above map. Bronze markers are embedded in the trail at 10 meter intervals with each marker representing the passage of 10-million years. This is the marker where I began:

If I turned right, I’d walk forward in time and reach the present day in about .6 mile. Turning left would both take me back in time and be a much longer walk – about 2.25 miles to the “oldest” rock formations. Opting to see how much of the nine plus miles between my starting point and the west end of the trail at Hermit’s point my rickety knees could cover, I turned left and started along the nicely paved path.

As you can imagine, Grand Canyon is a photographer’s dream – even one is as ordinary as I. While I was able to indulge in thoughts of fleeting profundity as I ambled along, the depth of those thoughts was interrupted by my frequent stops to take a picture. I noted the viewpoints only periodically so you might have to simply look at the pictures I took between the Trailview Overlook and Hermit’s Rest with stops at Maricopa Point, Powell Point, Mojave Point and Pima Point without clarification. Walk along with me and let me provide some, perhaps unfamiliar Grand Canyon facts and, along the way, also dispel some Grand Canyon myths.

So you think you know the Grand Canyon

Canyonwise, just how grand is it really?

Although the Grand Canyon is indeed grand, it is not, by almost any measure, the world’s grandest canyon. Now, simply defining a canyon as the largest or the deepest – let alone grandest – is (as is the case with so many measurements of this kind) problematic because it depends not only on how you choose the measurement standard but also on how you define the terms. Are you measuring depth? Length? Width? Volume? And each of these factors can be substantially influenced by the place and manner of the measurement.

With that said, there’s general agreement that, excepting a recently discovered canyon under Antarctica’s ice sheet discovered a year or so ago – the size of which isn’t fully known – the world’s largest canyon is the Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon in Tibet which has an average depth of 16,000 feet (compared to about 6,000 for the American Grand Canyon) and a deepest point of either 17,567 feet (according to the U.S. Park Service), 18,000 feet per Wikipedia or 19,714 feet if you believe Scribol.com. However, if you measure the depth of a canyon from the highest peaks on either side of the river at the canyon’s floor then the honor of deepest canyon belongs to the Kali Gandaki Gorge in Nepal with a depth of more than 22,000 feet.

(To toss a bone to my Australian brother-in-law, the Capertree Valley about 84 miles northwest of Sydney could earn a place near the top of the list because it’s a kilometer wider than the Grand Canyon though it’s neither as deep nor as long.)

I want my rocks back. All 950 million years of them

Although he was not a formally trained geologist, when John Wesley Powell (not the one who played first base for the Orioles from 1961 to 1974) completed the first documented trip through the canyon beginning on the Green River in 1869, (more on him and this expedition later) he noticed something amiss about the rock strata.

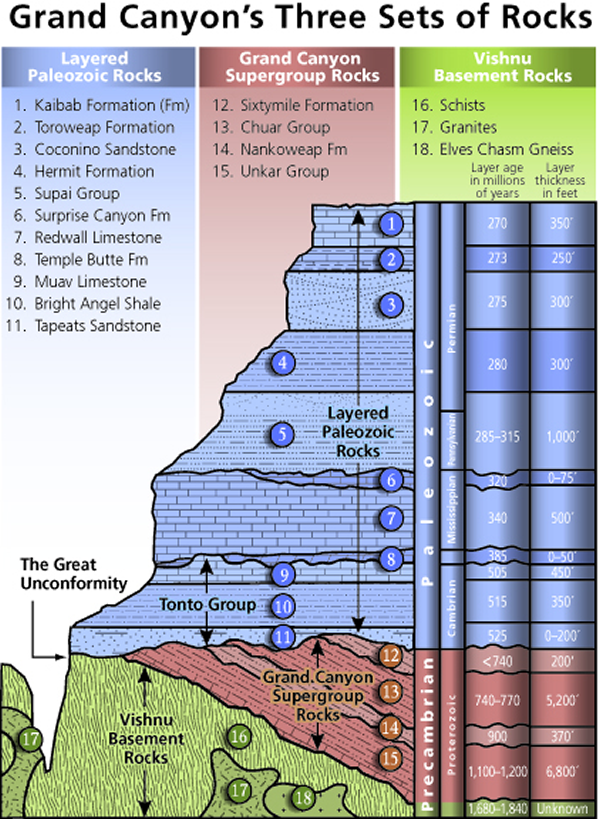

The Grand Canyon has three sets of rocks. The lowest set is the Vishnu Basement Rocks – a layer stretching back as much as 1.84 billion years. Above them is Grand Canyon Supergroup whose first deposits appear in the geologic record about 1.2 billion years ago. Then come the Paleozoic rocks beginning with the Cambrian era Tonto Group the oldest of which is 525 million years.

What Powell observed was rocks of the Tonto Group sitting directly atop the Vishnu Basement Group with no sign of Grand Canyon Supergroup rocks. This 950-million-year gap is known as the Great Unconformity. In this instance, the Tonto Group is separated from Grand Canyon Supergroup – which is not a band comprised of rock and roll megastars but rather a layer of faulted and tilted sedimentary rock – by what is known as an angular unconformity. The place where the Tonto Group abuts the metamorphic and igneous rocks of the Vishnu Basement Rocks is called a nonconformity. A nonconformity exists when the sedimentary rock lies above and was deposited on the pre-existing and eroded metamorphic or igneous rocks. It happens when the rock below the break is igneous or has lost its bedding due to metamorphism. For those who prefer a visual representation (from Wikipedia):

Powell’s Great Unconformity is of particular significance because it is part of a continent-wide unconformity that extends across Laurentia, the Paleozoic supercontinent comprising North America and Eurasia. It marks the progressive submergence of this part of the North American landmass by a shallow cratonic sea (a sea where the sea level experiences periodic and dramatic rises and falls thereby depositing layers of sediment onto an area of ancient rock called a craton) and its burial by shallow marine sediments of the early Cambrian. Continuing investigation including challenges to the orthodoxy could reveal a deeper truth but this is the best explanation we have at this time. It does mean that, until proven otherwise, we can be reasonably certain that no one stole nearly a billion years of rocks.

Note: In keeping with my 2022 reformation of the blog into shorter entries, backdated to maintain their sequence, any comments on this post might pertain to its new configuration. See the explanation in the post Conventions and Conversions.