The junkyard museum

There’s a scene about 20 minutes before the end of the 1983 cult movie Eddie and the Cruisers where the main character Eddie Wilson, frustrated by a music label’s rejection of his magnum opus, drives his girlfriend Joann past a sign that reads Wade’s Salvage before turning into what appears to be a junkyard. At one point he says, “You actually believed you could build a castle out of a bunch of junk.” A few minutes later, Joann refers to it a Palace Depression.

While the site in the movie is fictional, Palace Depression was (or perhaps is once again) a real place. It was a building made of junk built by, as described by Wikipedia, “the eccentric and mustachioed George Daynor, a former Alaska gold miner who lost his fortune in the Wall Street Crash of 1929.” The city of Vineland, New Jersey razed it in 1969 five years after Gaynor died but an effort to restore it began in 2007 that, according to Roadside America, had volunteer work ongoing as of August 2010. (Update 2023: The Palace of Depression is listed as a place to visit in Vineland on Trip Advisor.)

I cite this reference because, while the Miracle of America Museum (MoAM) in Polson, Montana makes no palatial pretense, it struck me as a monument of sorts to founder Gil Mangel’s obsessive collection of miscellany – both his own and from donations. Walking through the museum, I became convinced that he’d never turned down the donation of a single object. There’s so much on display that a person could certainly spend hours or perhaps days looking at it all – although I’m not certain why anyone would want to.

Unlike my decision to eschew taking exterior pictures at the Ninepipes Museum, the outside of the Miracle of America Museum at 36094 Memory Lane demanded it.

I don’t often encounter significant difficulty describing a place I’ve visited or my reaction to it but trying to write about the MoAM I’m engaged in just such a struggle. I’ll start with a bit of its history. With the support of his wife Joanne, Gil opened the MoAM in 1981 but its been something of a one man show since Joanne died in 2012 and it’s likely that Gil will be the person who greets you and takes your admission when you visit the MoAM.

If you ask him, he’ll tell you that the inspiration for amassing this collection came when he was in the military and served overseas. He’ll tell you quite passionately that his experiences reinforced the notion that the particular sort of freedom enshrined in the American Constitution and way of life is not merely precious but has fostered a spirit of innovation and creativity that he sees as unmatched by any other nation or culture. And he appears to have set out to amass as many artifacts as he can. (Not knowing the role his political views might have had in shaping the museum, I won’t delve into the very conservative politics evident in some of his displays beyond mentioning that this conservative view is quite evident.)

With minimal efforts at restoring the objects and no curatorial context, the MoAM somewhat brazenly bills itself as the “Smithsonian of the West.” A post written by Joanne in 1998 on the museum’s website boasts of

- extensive military display which includes over 20 vehicles, a large collection of home-front posters and memorabilia from several wars.

- Two dozen motorcycles from a restored 1912 Harley to a 1965 “Trike” and three large showcases of cycle memorabilia

- a 65 ft. logging tow listed in the National Register

- a bird-point arrowhead

- Montana’s largest collection of antique winter items to cope with or have fun on the ice or in the snow

- one of Montana’s largest barbed wire displays.

The last two are my favorite items from the list.

I think the description from Lonely Planet most accurately captured my experience,

At turns baffling and fascinating, these 5 acres are cluttered with the leftovers of American history: old motorcycles, bicycles, snow machines, steam tractors, antique quilts, coins, cast-iron skillets and countless other weird artifacts in a jumbled assortment of displays and piles.

Visiting the MoAM is an experience unlike any other. To appreciate it yet more, I’ll suggest you read some of the comments on Roadside America (particularly those on page 2), look at my pictures, or enjoy this video.

And it will remain a mystery

It was perhaps between 15:00 and 16:00 when I prepared to leave the MoAM telling Gil that my plan was to stop in Columbia Falls at the Montana Vortex and House of Mystery on my way to see what Glacier NP might have in store. He asked if I’d mind leaving a batch of brochures for his museum at the vortex and I told him I would be glad to do so.

The drive north was about 60 miles and would take about an hour with much of it conforming to the east shore of Flathead Lake which visitmt.com bills as the “largest natural freshwater lake west of the Mississippi in the lower 48 states”. (I included this citation because I’m frequently amused by the lengths promoters seek to find superlatives to describe something they want to be an attraction. Consider the number of qualifiers in the description and you can see that there are larger natural freshwater lakes in the lower 48 states but they are east of the Mississippi; there are larger freshwater lakes west of the Mississippi in the lower 48 states but they aren’t natural; and there must be larger natural freshwater lakes in Alaska but that state isn’t part of the lower 48.) Nevertheless, the route along Montana 35 also called E. Shore Road, stayed close to the lake for about 20 miles, and allowed occasional glimpses of it through the trees and thickening haze.

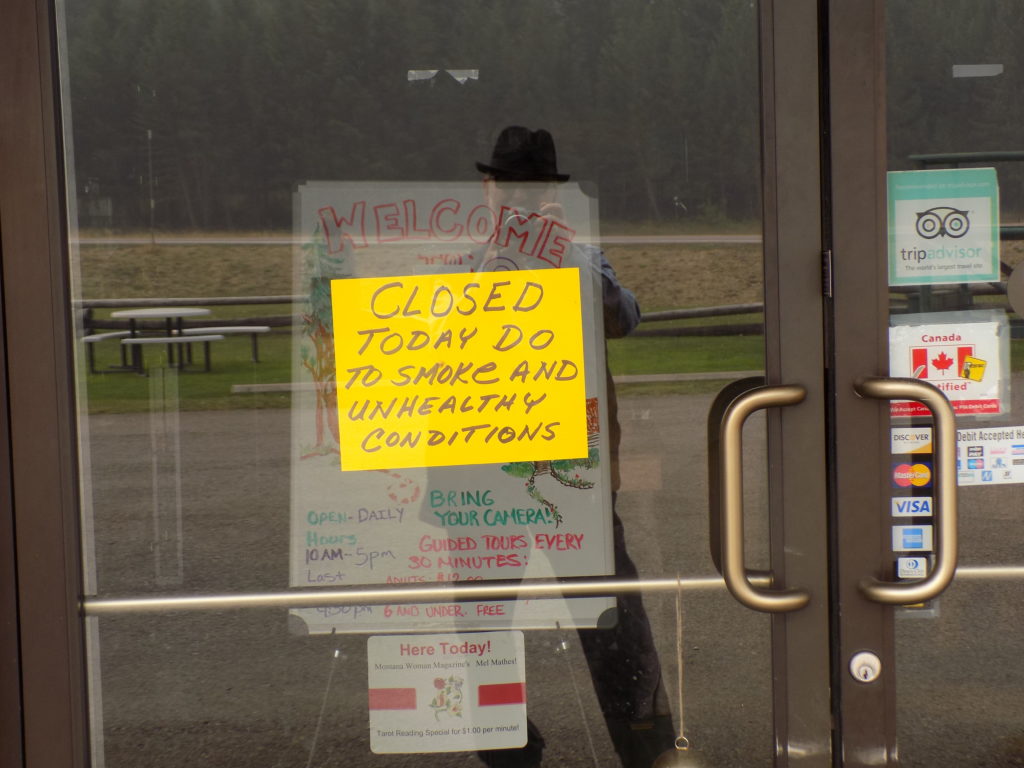

As gray as the air appears in the photo at the MoAM above, the ash grew noticeably thicker as I proceeded north toward Columbia Falls. I wasn’t terribly surprised when I reached the House of Mystery to see no cars in the parking lot because so many of the places I’d stopped had only one or two other visitors. I was, however, terribly disappointed when I walked to the door and saw this sign on the door.

I left Gil’s brochures on a barrel near the door and scrawled an explanatory note. To give you some idea of how thick the haze had become (and, believe it or not, it got worse on my drive around the southern section of Glacier NP before it got better) take a look at the photo below. The mountain behind the tower with the “Zip Lines” sign is no more than a quarter mile distant.

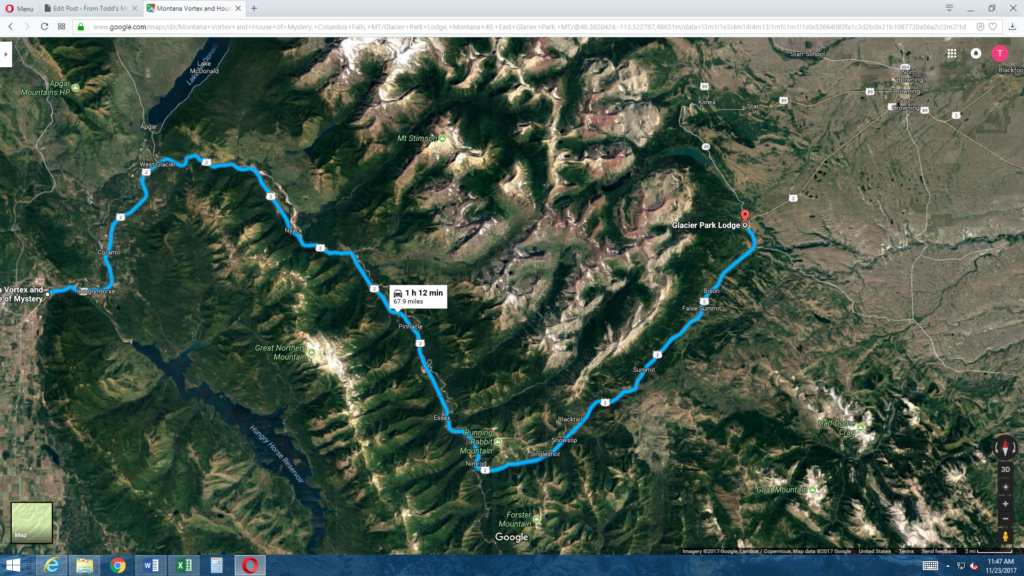

As I mentioned at the beginning of this post, I’d originally booked my stay at the Lake McDonald Lodge which is near the east end of that lake (you can see the lake at the top left of the satellite view below) and less than 25 miles from Columbia Falls. However, with the fires burning and the lodge closed, I’d been re-booked to the Glacier Park Lodge on the park’s east side. This was my new route.

Although the drive was, as the map shows, 68 miles or so, with the ash limiting my visibility, it took longer than the estimated time of an hour and 12 minutes. Still, the skies cleared a bit as I looped around to the south and east. I arrived safely, checked into my room,

Although the drive was, as the map shows, 68 miles or so, with the ash limiting my visibility, it took longer than the estimated time of an hour and 12 minutes. Still, the skies cleared a bit as I looped around to the south and east. I arrived safely, checked into my room,

took in the view from the shared veranda,

took in the view from the shared veranda,

(The apparent sunlight can fool the eye a bit. The haze is visible to the left through the trees.), and booked a bus tour for Friday with Sun Tours. This is when and where I first met Chris and Wendy from California (about whom I’ll have more to say later) and we both chose Sun Tours because it’s a Blackfeet owned and operated business. I then had dinner at the Great Northern Dining Room before settling in for the night.

(The apparent sunlight can fool the eye a bit. The haze is visible to the left through the trees.), and booked a bus tour for Friday with Sun Tours. This is when and where I first met Chris and Wendy from California (about whom I’ll have more to say later) and we both chose Sun Tours because it’s a Blackfeet owned and operated business. I then had dinner at the Great Northern Dining Room before settling in for the night.

Join me in the next entry for the Great Smoky Glacier Park Tour.