Normally, this is the post where I focus on the geology, geomorphology, or physiography of the city or region of the Olympic host city. However, since we’ve already taken an in depth look at much of Europe and since we’re talking about Paris, I’ve decided to take this chapter in a slightly different direction. In the initial post recounting my visit for this series, I made note of some of the icons of Paris that I failed to enter – the Louvre, the Eiffel Tower, and Sacré-Cœur. But perhaps the most essential part of Paris what I called in this post “le cœur et l’âme de Paris” – the heart and soul of Paris – is the River Seine. She will be the focus of the current entry.

Seeking Sequana

Imagine three travelers who each began a 600 kilometer journey to Île de la Cité Paris with a plan to meet one another at the most distant suburb of Paris at about the halfway point for each. One set out toward the west from Bern, Switzerland. The second, needed to travel in a more northwesterly direction from Geneva while the third, starting in Lyon, set a compass to near true north. Greeting each other warmly at the prescribed place, they found her in an artificial grotto 446 meters above sea level on Langres Plateau. Although they were still nearly 300 kilometers south of Île de la Cité, they were nevertheless in Paris.

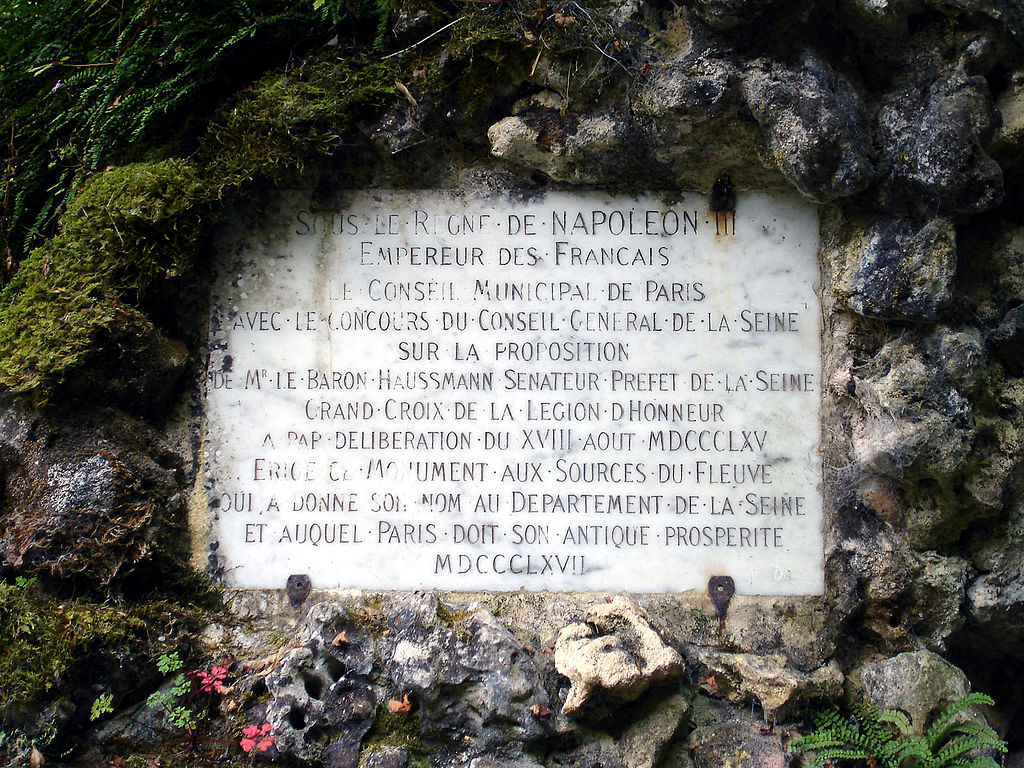

(Wikimedia Commons Christophe.Finot-CC-BY-SA-2.5)

(So critical to the identity of the French capital is la Seine that in 1864, Napoléon III purchased a part of the town then called Saint-Germain-la-Feuille – a name it had held since the Bourbon Restoration in 1815 – and claimed it as a part of Paris.

(Wikimedia Commons by Clicsouris-CC-BY-SA-3.0)

(In 1868, the town council requested that government allow it to replace la-Feuille with Source-Seine. It required seven years but the change became official in 1875. The grotto, statue and all, was designed and built by architects Gabriel Davioud, Victor Baltard et Combaz, and was installed soon thereafter.)

From humble beginnings

Those among you who have followed my travels for some time might recall my Great River Road journey which took me from the source of the Mississippi River nearly to its mouth and you might recall this photo

of me wading three fourths of the way across the river that will eventually flow more than 2,500 miles (more than four times farther than the Seine) to the Gulf of Mexico. It would make some sense, then, that the Seine would have an even more modest start to its flow. While the grotto in the photo above is generally considered the “primary source”, several small depressions or ditches such as this one

(Wikimedia Commons by Clicsouris-CC-BY-SA-3.0)

also feed the Seine at the source. The bridge in the distance is considered the first bridge to cross the Seine.

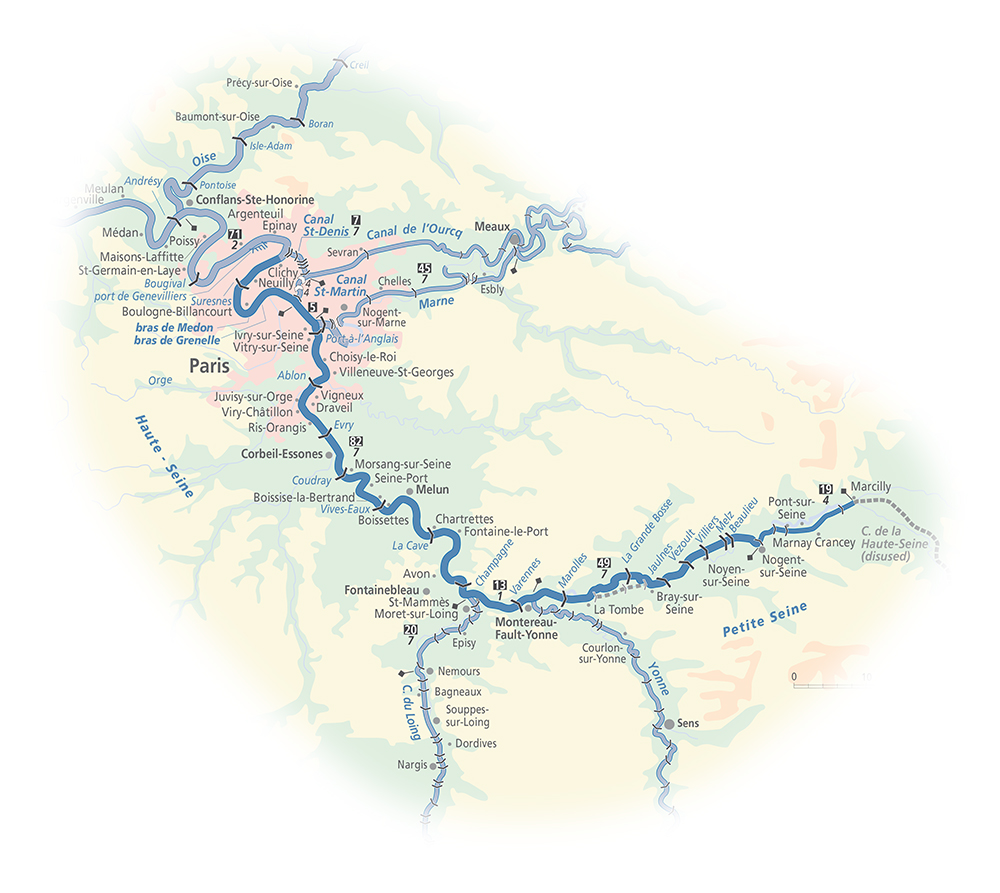

After paying appropriate homage to Sequana, the travelers resumed their journey carrying with them a small boat that they would be unable to use for at least another 84 kilometers when they reached the first navigable part of the river at Marcilly-sur-Seine.

They traveled in silence for a time before the eldest began to speak, “Although we saluted her, the statue we saw in the grotto,” she said, “was not of the ancient goddess Sequana. It is a nymph created by François Jouffroy in 1841 and is a little more fitting with sensibilities of the Romans and later Christians who came to control the place.”

“Tell us more,” one of her companions urged.

She continued her story. “The Celts who occupied this land were described by Julius Caesar in his Commentarii de Bello Gallico,” she continued, “wherein he described his nine year conquest of Gaul. He called them animists who ascribed human characteristics to lakes, streams, mountains, and other natural features. They typically conferred a quasi-divine status to them. Such was Sequana, the sinuous snake-like river that flows north to La Manche.

“The first shrine to Sequana was likely erected about 500 BCE and a healing shrine dedicated to her was erected some time in the first century BCE.

(Wikipedia by FULBERT-Own-work-CC-BY-SA-4.0)

“The Romans eventually built two temples there but while two pottery vessels with effigies of myriad body parts have been found, all that remains of the temples are their foundations.

“Theodosius I ordered the closure of all pagan temples at Source-Seine in the fourth century and that’s why the abbey of Sainte-Marie-de-Cestra now the Saint-Seine-l’Abbaye, although it was partially destroyed by the Germanic invasions at the end of the third century, is the only nearby religious institution. Even so, the belief in Sequana’s healing powers persisted well into the 18th and perhaps even into the 19th century.”

Geo-tech but short

After enjoying the appropriate wines along their way, having passed through Burgundy and Champagne and finally reached a navigable part of the river, the trio dropped their boat in the water at Marcilly-sur-Seine and paddled quietly for awhile as they continued their northward journey downstream toward Paris. After a time, the youngest of the three spoke, “Would you like to know a little about the land we’ve passed and will pass through,” she asked. Her companions nodded.

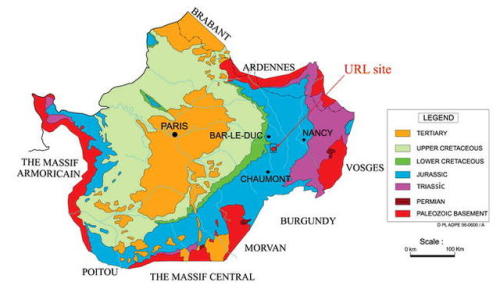

“As you know, we began our journey at Source-Seine on the Langre-Châtillonnais Plateau along the edges of the Massif Central and the Massif Morvan. The general makeup of the plateau is sedimentary oolitic limestone.” (Oolitic rocks result from the concretion of small regular spherical mineral structures formed during a sedimentation process with grains measuring 0.5 to 2mm.)

(From frenchwaterways.com)

“We crossed quickly into the Paris Basin where we’ll remain for the balance of our journey. Although the basement rock of the Paris Basin dates to the Variscan orogeny at the end of the Paleozoic some 250 million years ago, the oldest visible rocks date only to the Jurassic meaning the most ancient rocks we see will be no more than 60 to 70 million years old.

(From the-earth-story.com)

“A marine transgression into the Basin in the mid-Cretaceous deposited carbonate sediments sometimes hundreds of meters thick over large sections of Northwestern Europe. These permeable rocks with high absorption capacities, not only help to mitigate river floods but, in combination with a modest 700 mm or so of annual precipitation, provide the ideal conditions to grow the grapes that produce the wine we’ve been enjoying.

“But, geologically speaking, the critical time for the Paris Basin is the Pleistocene. Beginning 2.6 million years ago, this epoch spanned the Earth’s most recent period of repeated glaciations. During this period that lasted until about 12,000 years ago, periglacial processes interacted with fluvial erosion.” (Periglaciation is a geomorphic process that results from seasonal thawing of snow in areas of permafrost. The runoff then refreezes in ice wedges and other structures. Fluvial erosion is the detachment of material of the river bed and banks.)

More interested in enjoying the wine and the scenery, her companions merely nodded quietly.

“In the cold and mostly dry conditions, with continuous permafrost blocking water infiltration, rock disintegration was more efficient than dissolution in carbonate rocks. Under periglacial climates, the river carried and deposited thick layers of gravel. Triggered by the seasonal thawing of fluvial ice and snow, ice floes transported blocks of sandstone and limestone along the course of the river. Combine all of these processes and, although humans have intervened in many places to alter her natural course, la Seine becomes the lovely river of ever larger meanders we will encounter as we paddle farther and farther downstream to Paris and beyond.”

Continuing to paddle, her companions thanked her for giving them a newfound appreciation of the surrounding landscape and, of course, the wine.