Richard Norris Williams II who was generally known as Norris Williams was born on January 29, 1891 in Geneva, Switzerland. Although born in Switzerland, Williams was American by birth because both his father and mother were Americans. In fact, his father, Charles Duane Williams, who was instrumental in establishing the International Tennis Federation, was a direct descendant of Benjamin Franklin. When Richard turned 12, the elder Williams began coaching him in the sport of tennis – the sport that would eventually take him to the Olympic Games in Paris in 1924.

A Hall of Fame career

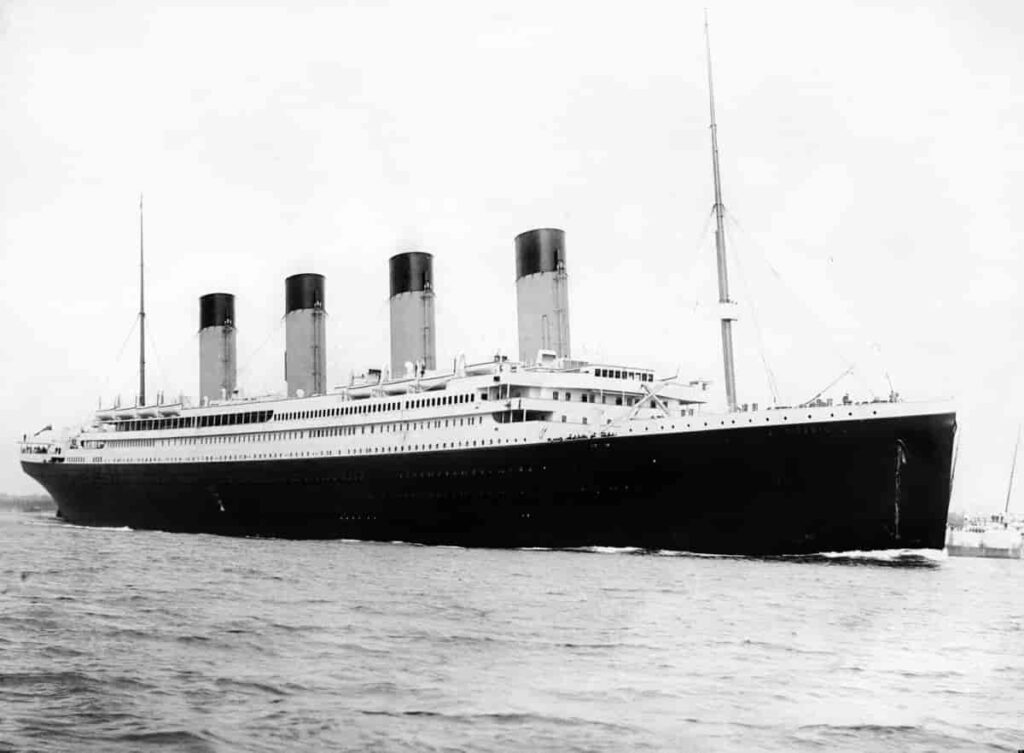

Those among us who have become accustomed to seeing teenagers competing as professional tennis players need to recall that for most of its history tennis, like golf, was a sport for amateurs and as such mainly the province of the upper classes. This was certainly the case when R. Norris Williams won the Swiss Championship in 1911. On 10 April 1912 with his father he boarded a ship in Cherbourg, France ultimately bound for the United States. The younger Williams planned to compete in some tournaments on the east coast before matriculating at Harvard University that fall while the elder planned to reunite with his wife who had returned to the U.S. sometime earlier.

Once he enrolled at Harvard, Norris

(From wearetennis.bnpparisbas)

Williams had a successful collegiate career winning intercollegiate singles titles in 1913 and 1915 and doubles titles in 1914 and 1915. He also prospered in other tennis competitions even while attending Harvard. He won the U.S. National Mixed Doubles Championship with Mary Browne as his partner and reached the 1913 final of the U.S. National Men’s Singles Championships where he lost in four sets to Maurice McLaughlin. He gained a measure of revenge the following year when he claimed that championship in straight sets over his erstwhile nemesis. He won a second title in 1915 and was continually ranked in the top 10 in the world from 1912 through 1914.

Although it delayed and probably to some extent derailed his singles career, Williams served in the U.S. Army during World War I. He served with enough distinction to win two of France’s highest military awards the Croix de Guerre (awarded to soldiers who distinguish themselves by acts of heroism involving combat with the enemy and whose heroism merited a citation from his headquarters) and the Legion of Honor (the highest French order of merit either military or civil).

After the War

When he returned to the court after the war, Williams’ greatest success came in doubles. Playing with a variety of partners, Williams won the 1920 Wimbledon Doubles championship and was the runner-up in 1924. On the west side of the pond, he appeared in five U.S. Championship finals winning twice. He was a member of four of the seven winning United States Davis Cup teams in the 1920s (and a captain from 1921-1926) posting a 6-3 record in singles and a perfect 4-0 in doubles.

Then, of course, in 1924, at age 33 he represented the United States in tennis at the Olympics. He reached the quarter finals in both the men’s singles and doubles competition but failed to medal because he had injured his ankle. However, he joined with Hazel Hotchkiss

(From wearetennis.bnpparisbas)

to win the gold medal in mixed doubles over fellow Americans Marion Jessup and Vincent Richards. The Olympics dropped tennis from its program after the Paris Games and it would be 64 years before another tennis player could win an Olympic medal. Norris Williams was inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame in 1957.

So what’s the big deal?

If R. Norris Williams had simply been a war hero and a champion tennis player his story might have merited a line or two in my summary of the Games. I hinted at it above when I specified the date he and his father boarded a ship bound for the U.S. The ship had set sail from Southampton, England earlier that day before it’s stop in Cherbourg where Williams père et fils boarded as first class passengers on a single ticket with the number PC 17597 that had cost £61 7s 7d (about $7,500 U.S. today).

The ship made one more stop at Queenstown, Ireland on 11 April 1912 where it picked up 63 men and 60 women – all second or third class passengers – before setting sail for the U.S. That ship never reached the United States because four nights after leaving Ireland on its maiden voyage, the R.M.S. Titanic struck an iceberg and sank in the North Atlantic.

(From snl.no Public Domain)

One of the more than 1,500 people who died that night was Charles Duane Williams. One of the 705 people who survived was Richard Norris Williams. Here’s some more from the Encyclopedia-Titanica:

As the Titanic foundered Richard and Charles found themselves swimming for their lives in the water, Richard was astonished to find himself face to face with first class passenger Robert W. Daniels’ prize bulldog Gamon de Pycombe doing likewise, one of the other passengers had earlier ventured below to release the dogs from the kennels.

Richard saw his father and many others crushed by the forward funnel as it collapsed, he narrowly avoided being crushed himself, the resulting wave washed him toward Collapsible A and after clinging to its side for some time he was hauled aboard; He and the other occupants were later transferred to lifeboat 14.

The survivors in Collapsible A had suffered terribly from the cold since they were waist-deep in freezing water. After his rescue the doctor on the Carpathia recommended the amputation of both his legs but Richard refused; he exercised daily and eventually his legs recovered.. {According to Wikipedia, his exercise regimen was “simply getting up and walking around every two hours, around the clock.”

A month later Collapsible ‘A’ which had been abandoned by the Carpathia was recovered by the White Star Liner Oceanic, as this letter, from R.N.Williams to fellow Titanic survivor Colonel Archibald Gracie shows, its discovery led to a certain degree of confusion regarding Williams and his father:

‘I was not under water very long, and as soon as I came to the top I threw off the big fur coat. I also threw off my shoes. About twenty yards away I saw something floating. I swan to it and found it to be a collapsible boat. I hung on to it and after a while got aboard and stood up in the middle of it. The water was up to my waist. About thirty of us clung to it. When officer Lowe’s boat picked us up eleven of us were still alive; all the rest were dead from cold. My fur coat was found attached to this Engelhardt boat ‘A’ by the Oceanic, and also a cane marked ‘C.Williams.’ This gave rise to the story that my father’s body was in this boat, but this as you see, is not so. How the cane got there I do not know.’

A mere 12 weeks after surviving the Titanic disaster, Williams would face off against the more experienced 27 year old Karl Behr – another future ITF Hall of Fame player. They met just outside of Boston in the fourth round of the Longwood Challenge Bowl. The young upstart Williams won the first two sets but the cagey veteran Behr mounted a comeback and won the match in five sets. The next day the Boston Globe wrote, “If one of the 1,500 spectators went away dissatisfied, he was indeed hard to please.” The reporter neglected to mention that Williams had survived the Titanic disaster. He also failed to note that, in a coincidental twist of fate that defies credulity, so had Karl Behr. You can read a little about Karl and his experience on board with his future wife Helen (not exactly Jack and Rose but definitely a Titanic romance) here.

“And now,” as Paul Harvey might have said, “you know the rest of the story.”

What a wild and improbable story! Fact, indeed, is stranger than fiction. The most amazing thing was that he was playing tennis just 3 months after being told his legs needed to be amputated – crazy!

The more I read, the wilder it got. I felt like I was watching an episode of One Step Beyond.

That sure is one hellva story there Todd.

I sorta knew something was up with this- when you mentioned the date of departure.

Not Hollywood Jack & Rose but real deal. Fate and fortunate to survive the sinking

let alone continue with their playing careers. If distinguished service in WWI wasn’t

enough- the possibility of both legs being amputated led to determination, grit, some

guts, perseverance to not give in when the odds are stacked against you.

I was entertained by your latest installment of World traveler and historian thereof.

Shell

I promised a HELL-va story and I’m glad you think I delivered. I wanted the date to hint but not necessarily reveal. Recognition for those who know and a little surprise for those who don’t.

Thanks to my buddy Dana D. for spotting a small typo that I have since corrected.