As with most organized tours, our first full day of activities began with a bus ride and a walking tour intended to provide some basic information about and a general orientation to the city. Though it rose from very small and humble beginnings, Paris is, as we all know, a large city so it’s reasonable to assume that an orientation would be helpful. Because the Performance Today tour was so large – about 145 people, we were randomly divided into three smaller and ostensibly more manageable groups who would reunite for a somewhat chaotic and hectic lunch after our morning orientation. The guide on our bus, Maeva, was lively and engaging though by the end of the morning I thought I’d learned as much about her personal life and tastes as I’d learned about Paris so I’ll try and guide you with the knowledge I gained using other sources before, during, and after the trip.

We started our tour at Paris’ Hôtel de Ville or City Hall or, perhaps more accurately, city administration building.

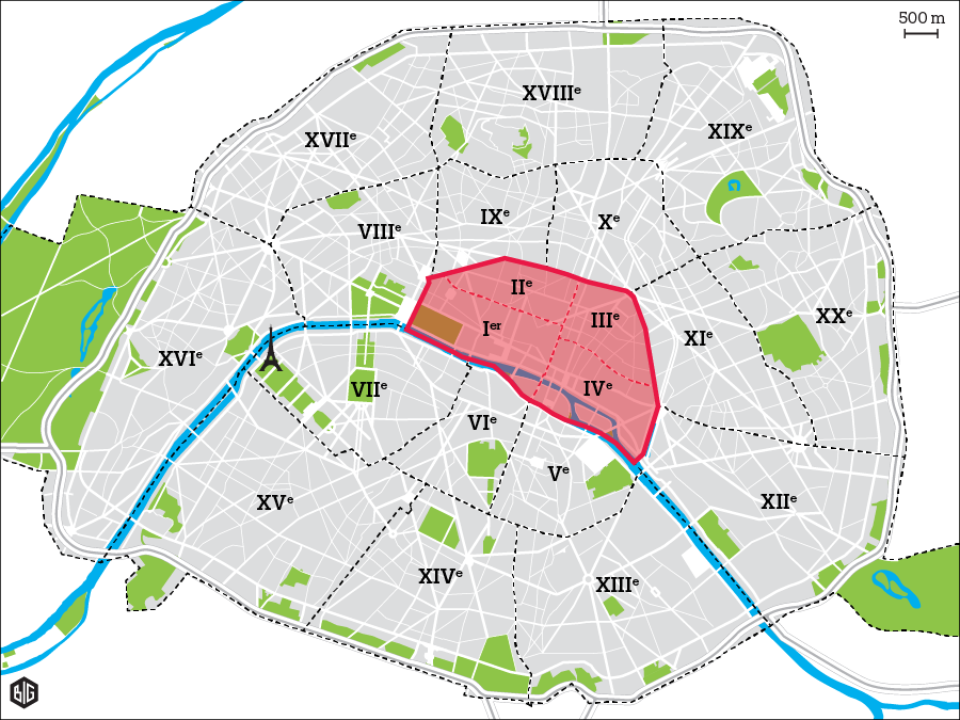

It’s located in the fourth arrondissement where, coincidentally, Patricia and I would stay on our return to the city. While one might think of each arrondissment as a neighborhood, each one is, in fact, its own administrative entity and if you look for them as you wander the city, even as a tourist you can spot each arrondissment’s local Hôtel de Ville.

Paris – City of Light or City of Mud?

Paris has been a cohesive municipal entity since 1834 – not quite two decades after Napoléon’s defeat at Waterloo. However, at that time, it was only half its modern size and was comprised of just 12 arrondissements. Then, in 1860, it annexed a number of bordering communes (the French term for municipality) creating the new administrative map of twenty municipal arrondissements seen in the city today. If you look at the map below and follow the Roman numerals, you’ll see how these municipal subdivisions trace a clockwise spiral outward (some describe it as a snail’s shell) from the center of the city starting from the first four arrondissements.

As I mentioned above, each of Paris’s twenty arrondissements has its own town hall. Additionally, each has a directly elected council (conseil d’arrondissement), which, in turn, elects an arrondissement mayor (mairie). Each arrondissement council then chooses a subset of its members to form the Council of Paris, which, in turn, elects the mayor of Paris. The current mayor of Paris is Anne Hidalgo. She is the first woman to hold the post.

Paris actually had no mayor for 183 years until the French Parliament passed a law that was signed by President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing on 31 December 1975 re-establishing the office. The city held its first formal election in March 1977. One-time Prime Minister Jacques Chirac was elected as the first modern mayor and served three six year terms before he assumed the office of President in 1995.

Sequana – le coeur et l’âme de Paris.

The soul, heart and, in some ways still major artery of Paris is the Seine River. One could say that, more than any of the familiar structures, it is the Seine that is definitively emblematic of the city. Left Bank. Right Bank. Île St. Louis. Île de la Cité. Without them, what is Paris?

The city’s earliest known settlements appear in the third-century BCE by a Gallic or Celtic tribe known as the Parisii who almost certainly relied on the River they called Sequana for transport and commerce and who, some believe, took their tribal name from a compound of Celtic words par+gwys that meant, more or less “expert canoe boatmen.”

In 52 BCE, the Romans, led by Julius Caesar, conquered the settlement, which might have been on the small islands in the now center of Paris and renamed the town Lutetia. Wherever the Parisii had settled, we can be certain that the Romans built their walled citadel or civitas on the island now called Île de la Cité or simply Cité. (Cité is probably a Gallic shortening of civitas.)

(A proud Frenchman might tell you that these “river people” gave rise to the new Roman name for the settlement claiming it derives from the Celtic luh [meaning river] + touez [meaning middle] + y [meaning house]. However, as David Downie, with whom I have a budding friendship and who also provided all the above etymologies notes, in the middle of the 19th-century Victor Hugo pointed out that there is a Latin word “lutum” that also appears closely related to Lutetia. Lutum means mud and thus the Roman name would have been the far less appealing “City of Mud”. Given the river’s propensity to flood, this seems equally plausible.)

The Romans controlled the area until 486 when a tribe called the Franks captured the city. Three hundred fifty-nine years later a tribe of Vikings or Norsemen led by a warrior named Ragnar (Reginherus) invaded northern France reaching Paris at the end of March during Easter. When they were through plundering the city, the French King Charles le Chauve (Charles the Bald) paid them a ransom of 2,750 kilograms of silver and gold and they withdrew leaving Charles considerably poorer and rethinking the city’s defenses.

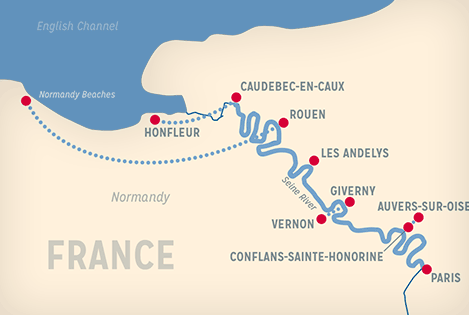

For the Gauls, Sequana meant snakelike and one can conclude with just one look at this map  that it’s certainly a fitting moniker. (You will also be able to refer to this map during my recounting of the river cruise since it marks many of the places we will visit.) Not particularly happy with the allusion, the Romans humanized the “snaky Sequana into a curvaceous water nymph of the same name.” According to Paris, Paris, the David Downie book I cited earlier, “a mid-nineteenth-century rendition of Sequana stands in a faux grotto at the Source de la Seine.” You can visit this spot, some 300 kilometers from the city center and still be in Paris because it was claimed for the city by Napoléon III. I’ll return to a geographically closer representation of the nymph when I visit the Pont Mirabeau later in the trip.

that it’s certainly a fitting moniker. (You will also be able to refer to this map during my recounting of the river cruise since it marks many of the places we will visit.) Not particularly happy with the allusion, the Romans humanized the “snaky Sequana into a curvaceous water nymph of the same name.” According to Paris, Paris, the David Downie book I cited earlier, “a mid-nineteenth-century rendition of Sequana stands in a faux grotto at the Source de la Seine.” You can visit this spot, some 300 kilometers from the city center and still be in Paris because it was claimed for the city by Napoléon III. I’ll return to a geographically closer representation of the nymph when I visit the Pont Mirabeau later in the trip.

Returning to the Hôtel de Ville.

Although it’s not the original building, the site where the Hôtel de Ville currently stands has been the site of the city’s administrative center since 1357 when Étienne Marcel – the provost of the merchants of Paris under King John II – (Jean le Bon or John the Good) purchased the House of Pillars and merged the space into the Place de Grève or “Gravel Plaza” adjacent to where the first harbor on the river had been established. It’s now called the Place de l’Hôtel de Ville. The Place de Grève was the site of most of the public executions in those early days. (Interestingly, the Place de Grève was also a place people congregated to seek work and this aspect has flowed into French usage today in the expressions être en grève and faire grève meaning to be on strike or to go on strike.)

By the early 16th-century, Paris was the largest city in Europe and King Francis I ordered the construction of a city hall appropriate to this stature. Construction of a Renaissance style building began in 1533 but wasn’t completed until nearly a century later in 1628.

Because it led to the founding of the First Republic, most people likely think of the revolution that began in 1789 when they hear the phrase French Revolution. However, the history of the republic is far more tumultuous and dotted with lesser uprisings and revolutions. One of these was the Paris Commune that sprung up as an outcrop of the Franco-Prussian War. The Commune ruled the city for a mere two months from 28 March to 28 May 1871 but the rule of the Commune proved destructive for the edifice.

Noteworthy for purposes of this discussion, when it became clear that the government was going to fall and anti-Commune troops were on the verge of capturing the Hôtel de Ville, the Communards set fire to the building destroying many of the records it contained and leaving only a stone shell remaining. When a new city hall was commissioned in 1873, the architects rebuilt the interior of the building while incorporating as much of the façade as possible so that even today the Hôtel de Ville retains the appearance of the 16th-century French Renaissance building.

Note: In keeping with my 2022-2023 reformation of the blog into shorter entries, backdated to maintain their sequence, any comments on this post might pertain to its new configuration. See the explanation in the post Conventions and Conversions.

What amusement! I almost lost my sip of Rose while reading the first paragraph. (I have felt the same about many beauticians I have endured.) I was wondering if you had an opinion about the redevelopment of the La Samaritaine building. I was extremely fortunate to briefly live in Paris (months, not years…in a 3 star hotel) and to encounter La Samaritaine while it was still a retail space. The interior was a joy just to experience. And the shopping… Perhaps commentary about this will appear in the next installment.

(and there are many memorable opportunities for great food in Paris. And not overly expensive, either. I hope you had an opportunity to find some when not on the tour.)

The truth is that neither Patricia nor I are particularly avid retail shoppers so we didn’t visit La Samaritaine. However, I’m fairly certain it was undergoing some sort of face lift. My memory pictures it behind one of those painted gauze scrims.

As for our meals, most of the meals we had in Paris were quite good though we rarely planned where we would eat. I’ll mention a few in time including Chez Mademoiselle which was, quite literally, below the flat we’d rented.