Reykjavik, Iceland is the only national capital city farther north than Helsinki, Finland. Helsinki is the northernmost city to host any Olympic Games. Thus, it would be reasonable to ask why Helsinki would host the Summer Games when the Winter Games seems a more natural fit. The short answer is topography. If you want to find mountains in Finland, you have to travel to the far northwest corner of the country to the Käsivarsi Wilderness Area. By the time you reach there, you’re at 69° north or nearly 3 degrees above the Arctic Circle. Even disregarding the problems of transportation and infrastructure, a typical February day has only about six and a half hours from sunrise to sunset. Hence no Winter Games for Finland. There were, on the other hand, Summer Games.

Building a city.

Sportsmen in Helsinki began thinking about bidding to host the Olympic Games soon after seeing the success Stockholm had in hosting the Games in 1912. The IOC rewarded their efforts by awarding the Finnish capital the 1940 Games. On my aforementioned bus tour, I managed to capture a glimpse of the Olympic Stadium

that was completed in 1938 in anticipation of the 1940 Games.

The political world had other plans, though, and the 1940 Games became a casualty of both the Second World War and the Winter War also known as the First Soviet Finnish War that began with a Soviet invasion of Finland on 30 November 1939.

Recall that London had been scheduled to host the Games in 1944 that had also been canceled so the IOC awarded that capital the first postwar Summer Games. Helsinki won the 1952 Games based largely on its having built or partially constructed many of the necessary venues.

[From Olympicsfandom.com.]

In terms of population, Finland is the smallest country to have hosted any Olympics and Helsinki, with its then population of about 380,000 remains the smallest city to have hosted the Summer Games. Even with many of the venues complete or under construction the city’s small size and relative isolation and its need to recover from the wars with the USSR (the Winter War and the Continuation War) left much to be done in Helsinki.

Probably the two largest projects were the construction of a new airport that remains in use today and the Olympia Terminal in South Harbor where my overnight ferry docked and departed.

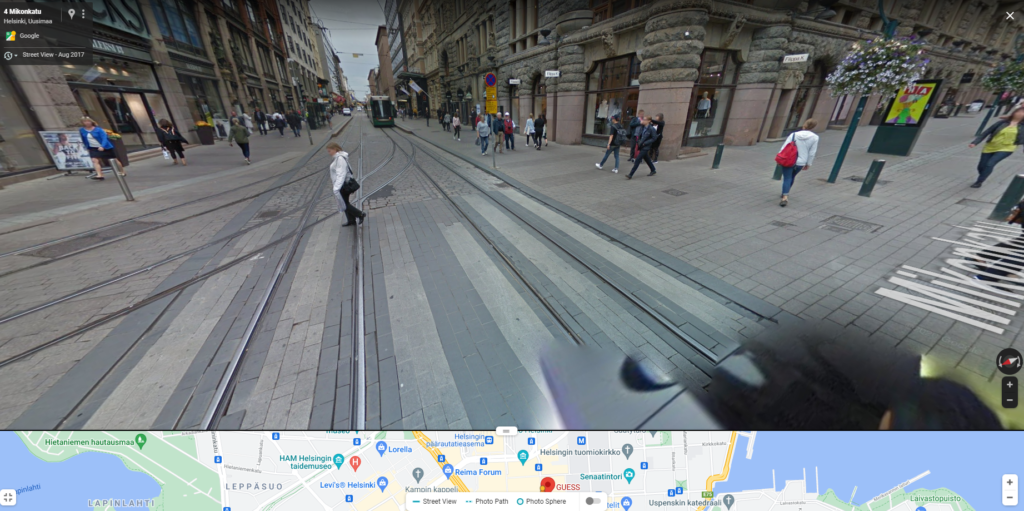

In order to accommodate the anticipated crowds, the city paved scores of kilometers of roads and installed its first traffic signal at the intersection of Aleksanterinkatu and Mikonkatu. Today, Mikonkatu is a pedestrian street as you might be able to see on the screen capture below from Google Maps.

Anticipating more visitors than actually appeared, private interests built several new hotels while the organizers erected ten villages within a few kilometers of the main stadium. One, a 6,000 bed facility in Lauttasaari – an island about three kilometers southwest of the Olympic Stadium – never had an occupancy rate above only eight percent of its capacity.

The first Cold War Olympics.

When the Soviet Union joined the IOC in 1951 with the intent of participating in the 1952 Helsinki Olympics, it set off silent alarms throughout U S politics and athletics. For a time, the U S considered withdrawing from the Games. The Soviets had invaded Finland in 1939 in the Winter War and had successfully beaten Finland’s attempt in the Continuation War to reclaim the territory it had previously lost. U S participation wasn’t assured until the Embassy in Finland provided a positive assessment of the situation and political stability. Then additional wheels started turning.

Leading up to the 1948 games, the U S Olympic Association stressed the importance of sportsmanship to American athletes in a way that could be summarized as “don’t humiliate our friends and allies.” With the Soviets now in the competition, President Harry Truman wrote to incoming USOC President Avery Brundage about the importance of a strong American performance, “Certain countries which have not participated for many years will be represented. Others will take part for the first time. . . . The eyes of the world will be upon us.”

Truman’s 1951 letter proved prescient. In the build up to the Games, Sovetsky Sport, a Moscow based athletics newspaper wrote, “Every record won by our sportsmen, every victory in international contests, graphically demonstrates to the whole world the advantages and strength of the Soviet system.”

At least one Olympian, Bob Mathias, felt the pressure, “There were many more pressures on American athletes because of the Russians than in 1948. They were in a sense the real enemy. You just loved to beat ’em. You just had to beat ’em. It wasn’t like beating some friendly country like Australia.” (Mathias won the Olympic decathlon in London in 1948 at age 17. He became the first to repeat as champion in Helsinki four years later.)

[Photo from Orange County Register.]

The situation wasn’t entirely clear cut on the Soviet side either. Initially, the Soviets planned to fly its athletes from Leningrad to Helsinki every day. When the Finns rejected that idea the new Soviet plan was to house them at the Porkkala Naval Base some 45 kilometers southwest of the city. (Porkkala Naval Base was leased to the USSR according to the 1944 Moscow Armistice that ended the Continuation War. The USSR returned it to Finland in 1956. Although the 1903 lease for Guantanamo Bay between the United States has Cuba has no technical expiration date, the U S has yet to mirror the Soviet gesture.) The Finns rejected this plan, too insisting that all athletes live in the Olympic Village.

In an effort to accommodate the Soviet insistence on isolating their athletes the Finns offered a compromise. They built a separate village to house not just athletes from the USSR but the entire Eastern Bloc (East Germany, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, and Albania).

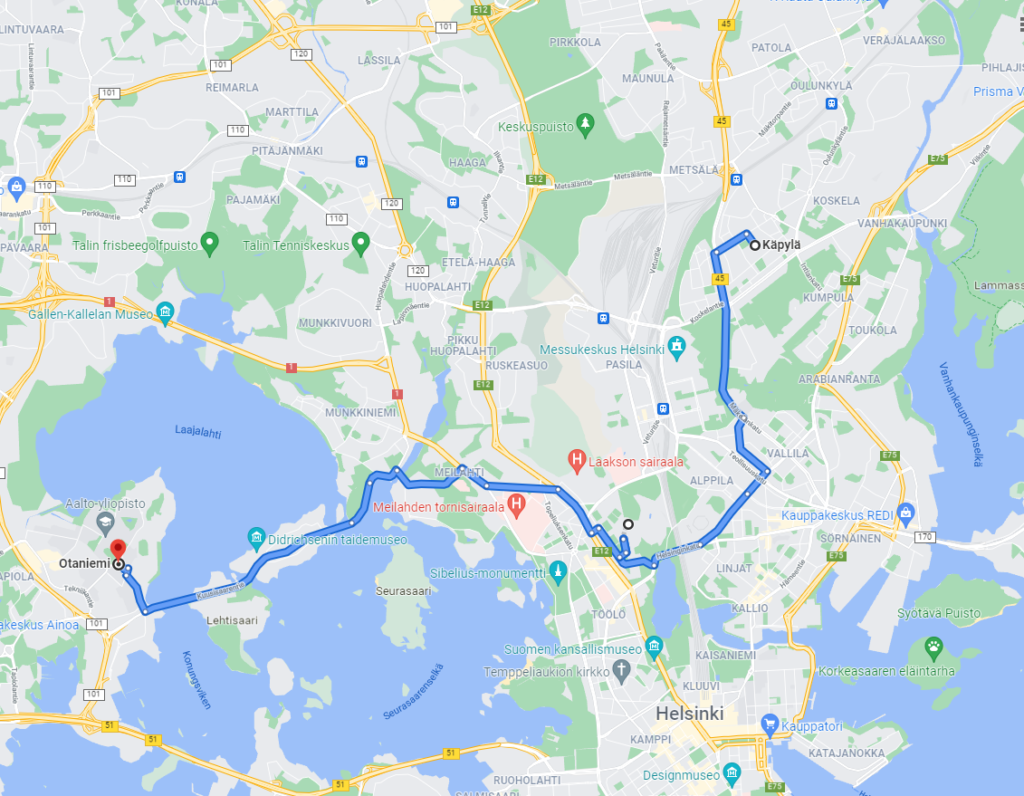

[From Google Maps.]

The main athletes Village was in Käpylä and the Village for the Eastern Bloc was in Otaniemi. The small black circle on the route between them is the Olympic Stadium.

As Erin Redihan wrote on processhistory.org, “Starting with Helsinki, the battle for hearts and medals would continue nearly unabated until the fall of the Berlin Wall.” I remain unconvinced that it stopped even then.

There was a competition, wasn’t there?

Indeed there was a competition. It featured 4,955 athletes (4,436 men and 519 women) from 69 countries competing in 149 events. The United States won the most gold medals 40 and the most total medals – 76 but the Soviet Union was close behind in second claiming 22 gold medals and 71 overall.

American men won the 100, 200, and 800 meter races including a podium sweep in the 200 and the men’s team overall won gold medals in 14 of the 23 events in athletics.

Australian Marjorie Jackson won gold in the 100 and 200 meters and was the only woman to win gold in more than one event in athletics.

Czechoslovakian runner Emil Zatopek provided the greatest highlight in athletics.

[Photo from Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain.]

After winning the gold medal in both the 5,000 (photo above) and 10,000 meter races, he decided at the last minute to run in the marathon – a race he had never run competitively. (One perhaps apocryphal story claims that Zatopeck decided to run the marathon because his wife, Dana Zátopková, won a gold medal in the women’s javelin throw and Emil stated that the family battle for gold medals was too close so he would win another in the marathon.) Zatopek didn’t merely win the marathon, he set a new Olympic record of 2:23:03.

The USSR began its dominance in gymnastics. In men’s gymnastics Viktor Chukarin won four gold and two silver medals while on the women’s side, Maria Gorokhovskaya won medals in every women’s event – Individual All-Around, Team All-Around, Individual beam, bars, floor and vault, and team portable apparatus. (Portable apparatus eventually became rhythmic gymnastics.) Her total of seven gymnastics medals (two gold and five silver) remains unsurpassed for a single Games.

I’ll end this post with a story that almost doesn’t seem like it could be true. But it is.

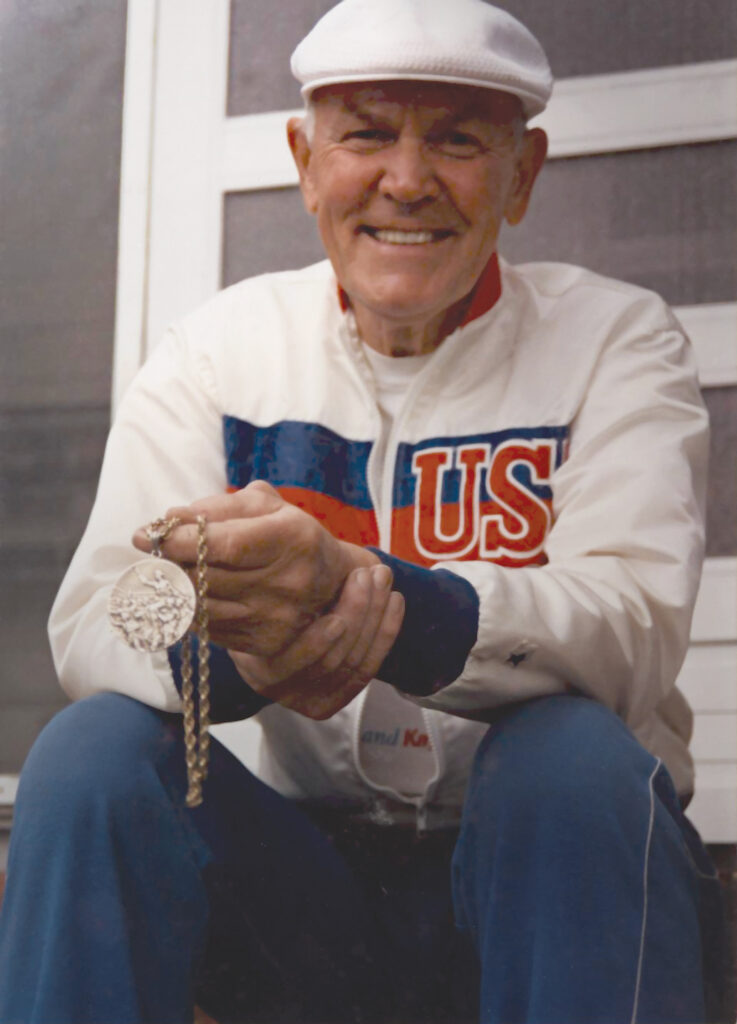

Canoeing was a demonstration sport at the Paris Olympics in 1924 and Bill Havens was one of the athletes chosen to represent the U S. He declined that opportunity choosing to stay home with his wife because their first child would likely be born during those Games. In 1952, that child, Frank Havens competed in canoeing in Helsinki. He won the gold medal in C-1 singles 10,000m – a medal that, as I write this, remains the only gold medal won by an American man in the sport.

[Photo from electriccoop.com.]