I first learned about the 1912 Olympics when I was probably as young as five or six years old. Among my older brother Steve’s favorite movies was a hagiographic biopic starring Burt Lancaster in the title role. That movie was Jim Thorpe – All-American and for me, if you knew the story of Jim Thorpe, you knew the story of the 1912 Olympics.

Thorpe was a Sauk Indian who competed under his anglicized name. He won both the pentathlon and decathlon. Thorpe won four of the five events in the modern pentathlon and four of the 10 decathlon events while finishing no worse than fourth in any of the ten. He set an Olympic and world record of 8,413 points that stood for almost 20 years.

And, because 15 events weren’t a strenuous enough challenge, he also competed in the high jump (where he finished fourth) and the long jump (seventh). A look at this iconic picture and the (possibly) apocryphal legend that accompanies it makes his feat all the more remarkable.

(Wikimedia Commons – Public domain.)

Look closely at his feet. You should notice that he’s wearing two different shoes and several socks on his left foot. The story is that someone had stolen his shoes just before the start of the competition, that he found some discarded shoes in a trash can and won his medals wearing those found shoes but had the extra socks because the shoes he found were different sizes and the left shoe was too big for his foot.

In those days the custom was to award athletes their medals at the close of the games. In presenting the medals to Thorpe, Sweden’s King Gustav V is alleged to have said to Thorpe, “You, sir, are the greatest athlete in the world.”

Part of the tragedy of Thorpe’s life was that the International Olympic Committee stripped him of his medals in 1913 because he violated amateurism rules by accepting expense money for playing minor league baseball prior to the Games and had the temerity (or foolishness) to do so under his real name rather than an alias. (He also had the temerity to be an Indian but that’s another tale.) In 1982, the IOC reversed the old ruling because the protest hadn’t been filed in the allotted time. His records were restored (though he was listed as a co-champion) and replicas of his medals were presented to his family in 1983. Thorpe had died in 1953.

And now, the rest of the story.

Although the underlying reasons are different the bidding process for hosting the 1912 Games mirrors the present circumstances because Stockholm was the only city to make a bid and while the 1908 Games in London had restored some of the sophistication the IOC thought had been lost in St. Louis, it wasn’t enough for IOC President and founder of the modern Olympic movement, Pierre de Coubertin. Coubertin was clear about his concern saying, “…the Games must be kept more purely athletic; they must be more dignified, more discreet; more in accordance with classic and artistic requirements; more intimate, and, above all, less expensive.” – a statement that drips with irony in the 21st century.

(Wikimedia Commons by olympic-museum.de Poster By Olle Hjortzberg).

Certainly, the IV Olympiad in London contributed to the growth of the Olympics by nearly doubling the number of participating countries from 12 to 22 and more than tripling the number of competitors from 651 to 2008. That growth continued in Stockholm with 28 nations and 2406 athletes.

Chile, Egypt, Iceland, Portugal, and Serbia participated for the first time. They were joined by Japan which became the first Asian country to compete in the Olympics. Serbia’s appearance was the only time it attended an Olympic Games as an independent nation until the 2008 Summer Olympics, almost one hundred years later.

The Olympic Stadium, which was constructed for the games

(Wikimedia Commons BY DERBETH Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0).

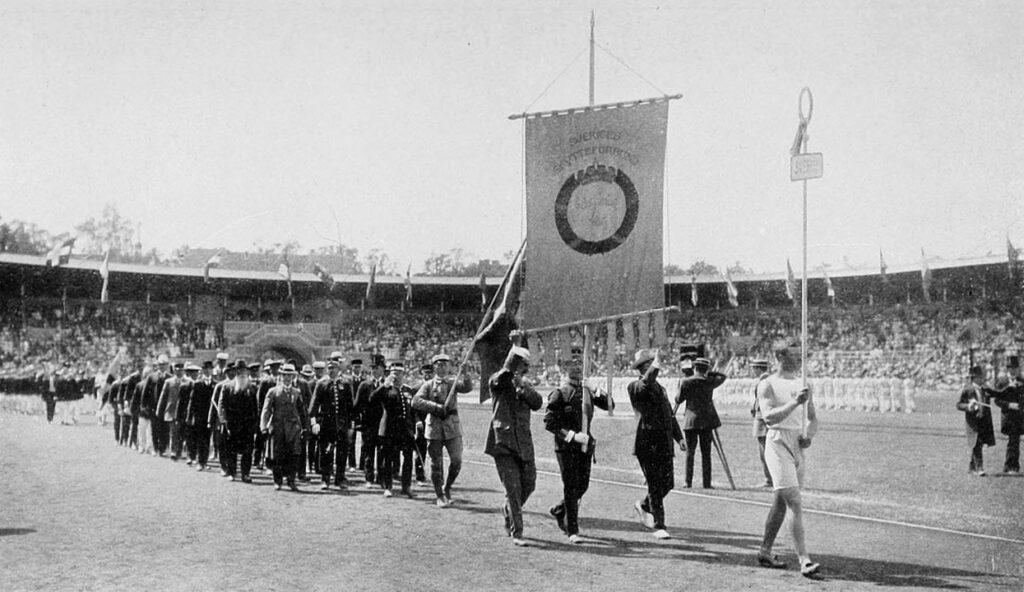

hosted the Opening Ceremony as well as athletics, some of the equestrian, some of the football (soccer), gymnastics, the running part of the modern pentathlon, tug of war, and wrestling events. After the royal family arrived, the athletes who had assembled at the Östermalm Athletic Grounds marched in alphabetically by the Swedish names with the Swedish team entering last.

(Wikimedia Commons Public domain.)

King Gustav V officially opened the Games.

New competitions and innovations.

The Stockholm Olympics introduced two technical innovations that would become staples not only of future Olympic Games but all similar competitions. The first was an electric timing system. It was invented by a man named Carlstedt and involved attaching electromagnets to stopwatch type devices which triggered a control lamp when the starter fired his gun. A judge at the end stopped the timer manually. The second innovation was having a camera for use in a photo finish and that was needed to determine the winner of the 1,500 meter race.

As I noted above, these Games introduced the modern pentathlon. They set the standard format for the decathlon, as well.

Women benefitted from some of the new sports added. For the first time women participated in swimming (two events) and diving (one event). The swimming events were the 100 meter freestyle and the 4 x 100 relay. Australian Fanny Durack won the gold medal and is seen here with teammate and silver medalist Mina Wylie.

(Wikimedia Commons – Public domain.)

The team from Great Britain won the relay race. The United States didn’t field its first women’s swimming team until the Antwerp Games in 1920 where they swept all seven gold medals and by 1924, the Americans would send the largest women’s team from any country. (The First World War canceled 1916 Games scheduled for Berlin.)

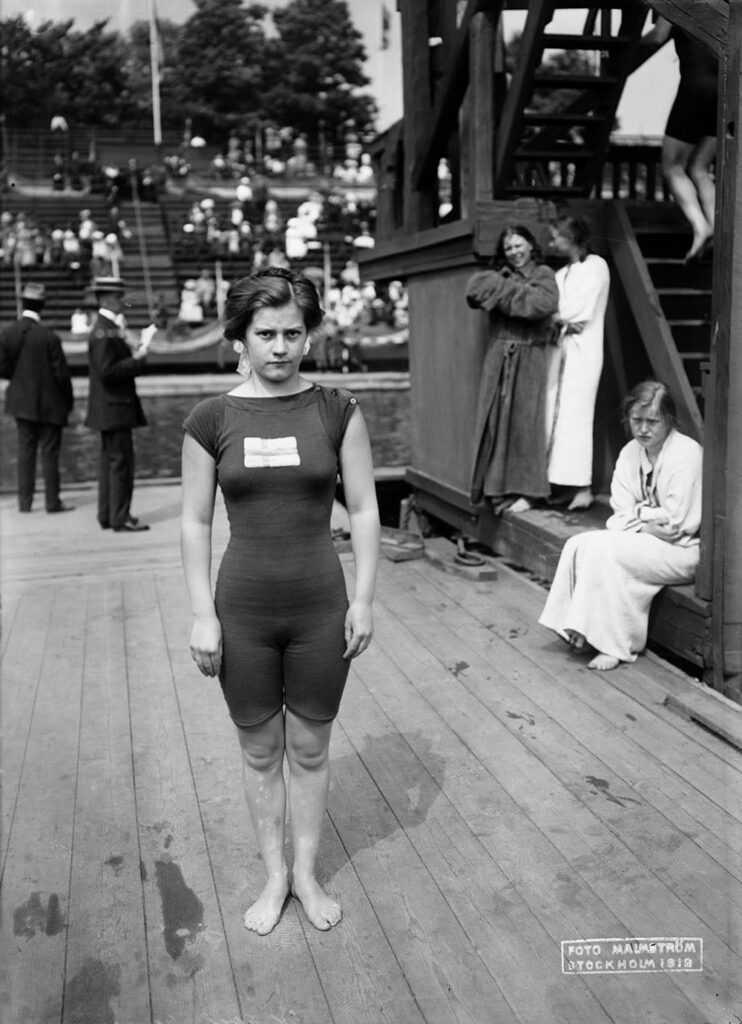

The lone diving competition was a 10-metre platform event. Sweden’s Greta Johansson and Lisa Regnell took gold and silver. Johansson (below) was Sweden’s first female Olympic champion.

(From europeana.eu StaadsMuseet).

Other than bronze medal winner Isabelle White from Great Britain, all the remaining finalists were from Sweden.

Five of the six finalists in the 100 meter dash were American and unsurprisingly, the the U.S. swept the medals with the gold going to Ralph Craig.

Hawaiian Duke Kahanamoku, perhaps better known for popularizing the sport of surfing especially in Australia and on the west coast of the United States, won the 100 meter freestyle for the United States.

(Wikimedia Commons – Public domain.)

The U.S. won the most gold medals (25) but Sweden’s 65 topped the overall medal count.

There was no boxing tournament because the Swedish organizers deemed the bellicose sport too offensive.

The 320 kilometer cycling road race remains the longest race of any kind in Olympic history.

The other marathon men.

First, the marathon wrestlers.

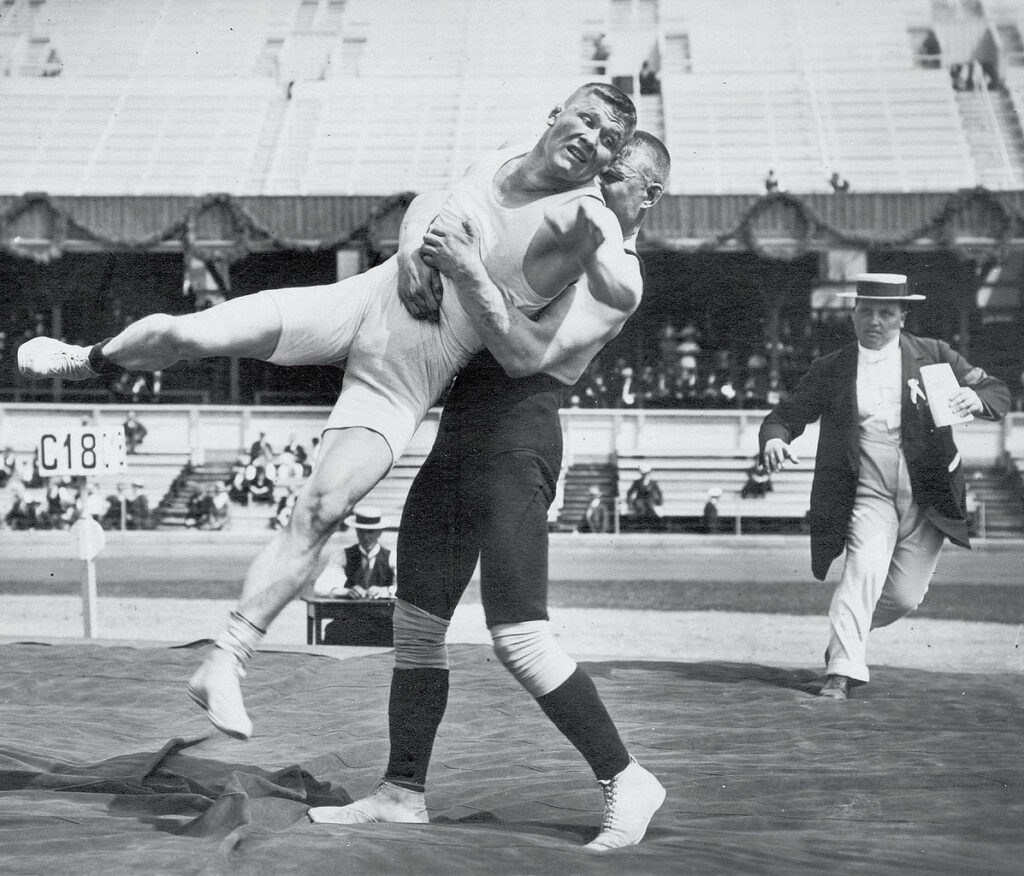

The light heavyweight gold medal match between Anders Ahlgren of Sweden and Ivar Böhling of Finland for the gold medal lasted more than nine hours before Böhling won the title. But that match was nothing compared to the middleweight semifinal match between Martin Klein of Russia and Alfred Asikainen of Finland.

(Wikimedia Commons – Public domain.)

That tussle went on for 11 hours and forty minutes although the men took breaks for refreshments every half-hour. Klein won the match but was too exhausted to wrestle in the final thereby handing Sweden’s Claes Johanson the host nation’s only wrestling gold medal.

In running marathon news, Portuguese runner Francisco Lázaro died from heat exhaustion during the race. He is the only athlete to die during the running of an Olympic marathon.

Then, there’s the tale of Japanese marathoner Kanakuri Shizō who boasts the slowest unofficial time in Olympic marathon history. You see, like Lázaro, he also suffered heatstroke. Unlike Lázaro, Shizō lost consciousness but he was spotted and revived by a farming family. After recovering, Shizō caught a train back to Stockholm and left the country the next day returning to Japan without notifying race officials. A half century later Swedish authorities invited him back and he completed the race finishing with a time of 54 years, 8 months, 6 days, 8 hours, 32 minutes and 20.3 seconds.

And then there’s Melbourne.

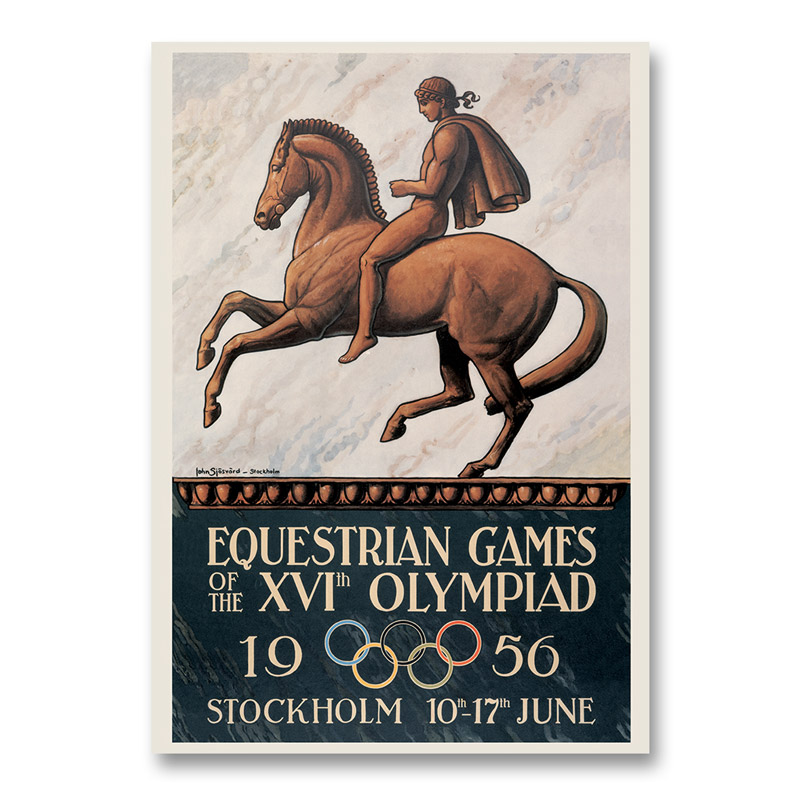

Melbourne, you ask. Yes, Melbourne, I reply. Melbourne hosted the games of the XVI Olympiad in 1956. However, they didn’t host the equestrian competition. Stockholm did. At the time, Australia had a strict six-month pre-shipment quarantine on horses and as early as 1953 Australian federal authorities ruled that they wouldn’t change the quarantine laws for the Olympic horses (or top ranked tennis players in 2022, apparently). So, in 1954, the IOC selected Stockholm as the alternate venue for the equestrian competition.

Notice the date which fell in the middle of the Australian winter. Thus, the equestrian competition was held in a different city, a different country, on a different continent, and in a different season from the rest of the Games which took place in November. Best of all, there were 158 entries from 29 countries including, ironically enough, the first appearance by Australia in equestrian events.

Notice the date which fell in the middle of the Australian winter. Thus, the equestrian competition was held in a different city, a different country, on a different continent, and in a different season from the rest of the Games which took place in November. Best of all, there were 158 entries from 29 countries including, ironically enough, the first appearance by Australia in equestrian events.

Great piece on Jim Thorpe. He was considered possibly the greatest athlete ever. Unlike me, although I can do a marathon in less than 54 years.

Thanks AK. 54 years 🤣