If you didn’t know that Molière was the stage name of Jean-Baptiste Poquelin before visiting his cenotaph in Père-Lachaise,

you’d at least have some idea from reading the marker. I point this out because if you visit the grave site of Victor Noir in the same cemetery, you’d leave not knowing that his given name was Yves Salmon. While Yves Salmon remains unknown, two separate legends grace the name Victor Noir.

Yves Salmon was born on 27 July 1848 in Attingy (Vosges département and région of Grand Est). Like many young men, Yves was uncertain about the direction of his life. He trained first to be a watchmaker but, perhaps realizing he was no Beaumarchais (or even Lepaute), left that profession to become a florist. Dissatisfied with that, too, he joined his brother Louis who was living in some comfort in the Parisian suburb of Neuilly-sur-Seine. While there, Yves discovered his calling.

He became the equivalent of a freelance journalist adopting the pseudonym Victor Noir. After a time, he began working for a newly established paper La Marseillaise owned by Victor Henri Rochefort.

Whether Rochefort – who was also the Marquis de Rochefort-Luçay – absolutely shared the Legitimist views of his father Edmond or if his politics were colored by the reportedly republican viewpoint of his mother, he was publicly and frequently very much at odds with the Second French Empire and the Bonapartist regime of Napoléon III. (A Legitimist was a royalist who adhered to the rights of dynastic succession to the French crown of the descendants of the eldest branch of the Bourbon family.) Rochefort was also a yellow journalist who late in life became known as “le Prince des polémistes” or the Prince of press controversy.

Both the international and domestic policies of Napoléon III were capricious and often misbegotten. Napoléon III came to power in 1852 but support for the emperor began to crumble by the late 1860’s and La Marseillaise worked to erode that support even more. Paschal Grousset, Rochefort’s editor at La Marseillaise, was even more radical than his publisher and was influenced by a new strain of political and economic thought that was spreading across Europe and latterly across France. Those ideas sprung from the mind of Karl Marx who had published Das Kapital in 1867.

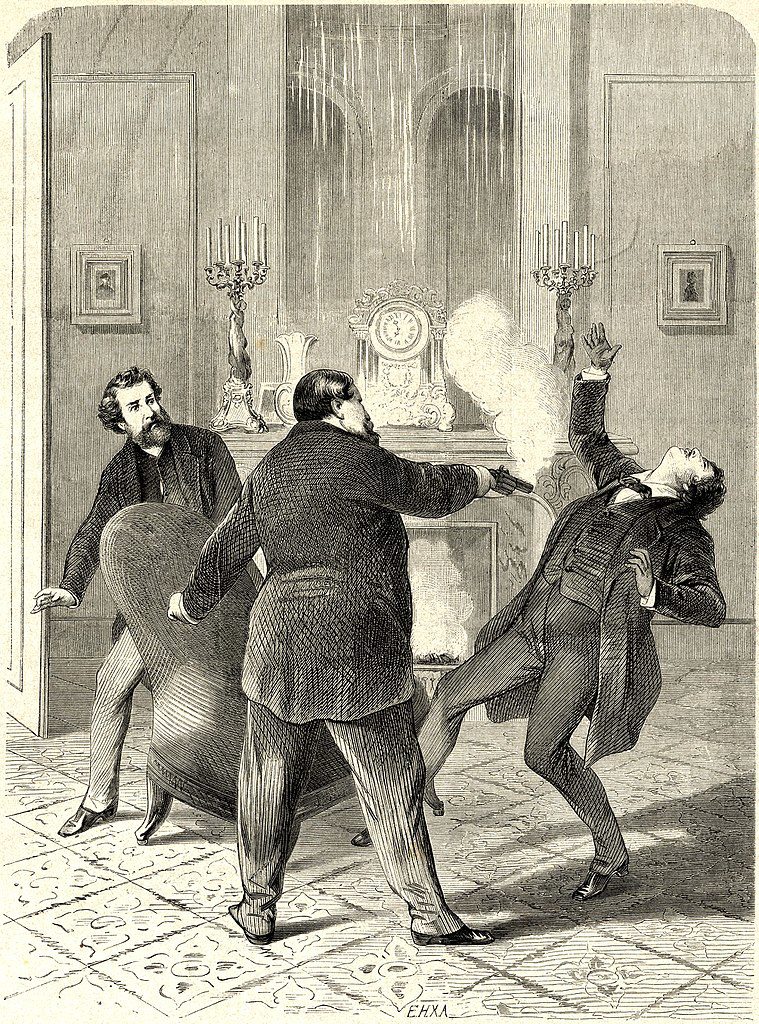

A dispute with Grousset and Rochefort on one side and Napoléon III’s nephew Pierre Bonaparte on the other so incensed Grousset that he believed his only recourse was to challenge the prince to a duel. He sent Noir and another of the weekly paper’s employees, Ulric de Fonvielle, to issue his challenge. This engraving from Wikimedia France imagines what happened next.

And it is in this moment that the legend of Victor Noir begins. The murder of a journalist by a member of the Emperor’s family was perfect fodder for opponents of the regime to exploit as a symbol of their opposition. Rochefort eagerly played a role in promoting Noir’s legend.

By the day of Victor Noir’s funeral, an enormous crowd numbering in the tens or some said hundreds of thousands had amassed outside his family home in Neuilly. The family had planned a quiet burial in the small local cemetery but the mass of people filling the streets demanded a triumphant procession through Paris and burial at Père-Lachaise. Victor’s brother Louis appeared imploring the crowd accede to the family’s wishes and allow his brother’s burial in Neuilly. His pleas succeeded. The throng eventually dispersed and the burial took place in Neuilly.

Although they left his body in Neuilly, the crowd still carried Victor Noir the symbol back to Paris. Protests around his murder continued undermining Napoléon’s hold on power enough to force the Emperor to consent to his nephew’s arrest and imprisonment (at the Conciergerie, of course). Two months later, after what was essentially a show trial, Pierre was acquitted.

The Empire eventually fell after a series of military defeats by the Prussians culminating at the Battle of Sedan in September 1870. This led to the formation of the Government of National Defense that held sway until February 1871 when Adolphe Thiers was elected Chief Executive of a new government by the National Assembly.

Despite the election of Thiers, unrest continued and Noir’s name became associated with many revolutionary activities. The unrest came to a head in March 1871, just a month after the National Assembly had elected Thiers, when the Paris Commune was established. As noted in an early post, the Commune governed Paris until May its defeat climaxing in what became known as “Bloody Week” when much of Paris burned.

(The ultimate battle of Bloody Week occurred in Père-Lachaise. There, 147 members of the last group of leftists defending the Commune were forcibly marched to what is now known as Communards’ Wall and massacred.)

(We didn’t visit the Commune Memorial. This photo is from Wikipedia.)

Hundreds of people involved with the Communard government were captured and exiled and for two decades relative quite draped both the Third Republic government and the remains of Victor Noir. Slowly, however, the Communard exiles began returning to Paris. Among them was the sculptor Jules Dalou who had attended Noir’s funeral in Neuilly.

Perhaps because the legend had grown up around him as an early martyr to their cause, their return sparked renewed interest in Victor Noir. Once again, calls were heard demanding a suitable spot for Noir in Père-Lachaise. Supporters launched the 19th century equivalent of a Go Fund Me campaign to raise the funds needed to exhume and move the body. They chose Dalou to create a sculpture to adorn the grave and, in 1891, the remains of Victor Noir were moved to Père-Lachaise where his tomb became something of a shrine to revolutionaries of the era.

(In a bit of a macabre twist, when Noir was moved from Neuilly, not all of him made it to Père-Lachaise. It’s been reported that as the remains were being removed from his original burial spot, Victor’s brother Louis asked to be left alone for a moment alongside the coffin. A witness later declared later that he saw Louis removing his brother’s skull though he said nothing to anyone else at the time. Apparently, Louis kept the skull in a glass case in his home. After Louis died, Victor’s skull was taken to his tomb in Père Lachaise where it joined the rest of his body.)

Before his murder, Noir had no reputation as an activist and little is known about his personal beliefs. Thus, in another twist Noir became a revolutionary symbol despite leaving behind scant evidence that he was an activist, let alone a revolutionary. Instead, he appears to have been an individual who found himself in the wrong place at the wrong time confronted by the wrong person in the wrong mood.

As it had in the two decades after the Paris Commune, the memory of Victor Noir gradually receded into obscurity. But sometime in the 1970’s people began noticing something peculiar about the work of Jules Dalou that adorned Noir’s grave and this turned Victor Noir into a totally different sort of symbol.

In some ways Dalou created a realistic portrayal of the scene of Noir’s death – a supine victim looking somewhat elegant with his hat at his feet. Ignoring for a moment its now most famous element, the artist created an idealized version of Victor Noir. The heroic, romantic, handsome, and svelte figure portrayed by Dalou isn’t an accurate picture of the somewhat overweight plodding young man that Noir reportedly was. But Dalou’s sculpture also so exaggerated one part of Victor Noir’s anatomy

that it eventually turned a chubby, nondescript man who died a few months shy of his 22nd birth anniversary, who was engaged to a girl five or six years his junior, and who was quite probably a virgin into a sex and fertility symbol.

One report ascribes Noir’s rise to the status of fertility symbol to a group of 1970’s tour guides who creatively spurted a legend that infertile and sexually unsatisfied women who rub – or in some cases mount – the hard evidence of Noir’s delight in seeing them will be afforded relief in all aspects of their sexuality and fertility. The full treatment appears to entail not merely rubbing the crotch but kissing him and rubbing his shoes as well.

Whatever the genesis of the legend, those three areas of his memorial that have been rubbed clean of the green oxidation evident on the rest of Dalou’s statue provide evidence of the pattern. In fact, hoping to protect the sculpture, the government erected a fence around it in 2004. This led to such howls of protest that the fence was quickly removed and the grave of Victor Noir – perhaps the unlikeliest of revolutionary heroes and sex symbols – is among the most visited in Père Lachaise today. As it’s cheekily described on Atlas Obscura,

“Erotic Erosion: The Recumbent Effigy of Victor Noir

Victor Noir’s effigy gets more action than the man himself ever did.”

Coming up, a spirited pseudonymous Spiritist.