In the first éditions of the Père-Lachaise Chronicle, I reported on the lives of the two men whose monuments in death, it seemed to me, exceeded their achievements in life – albeit for two quite different reasons. The coming stories focus on two men each of whom I think exploited a very basic human desire but each used different methods and and had unrelated motives.

Sleight of hand – dealing from the bottom of the Kardec.

As I noted in my first post about our cemetery visit, Père-Lachaise is the burial place for scores of people of national and international renown and a celebrity’s grave is, for some, an attraction. Some among the living are drawn solely by virtue of the deceased’s celebrity – it’s the closest they are likely to get. Others are drawn for quite personal reasons. Sometimes, as was the case for Abélard and Héloïse or as is the case of Victor Noir, motives can be deduced based on the public’s knowledge and it’s the latter, I believe, that is the case for the first story in today’s édition.

The occupant of the first grave we’re viewing today is, like those of Jim Morrison or Victor Noir, among the cemetery’s most visited sites.

This is the grave of Hippolyte Léon Denizard Rivail who, under the name Allan Kardec, founded and codified the spiritualistic religion known as Spiritism.

Rivail was born in Lyon in 1804 to a Catholic family but spent many of his formative years being educated in mainly Protestant Switzerland. He left home at age 10 to attend the primary school in Yverdon-sur-Bains founded by one of the great educational reformers of the late 18th and early 19th-centuries – Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi. By the time of his death in 1831, Pestalozzi, whose Romanticist approach to education was captured by his motto, “Learning by head, hand and heart” had succeeded in virtually eliminating illiteracy in Switzerland and Rivail carried and propagated Pestalozzi’s lessons through his life.

The Romanticist approach, that stressed emotion and individualism, likely appealed to the young Rivail who showed his pedagogic tendencies when he began tutoring his fellow students at the tender age of fourteen. His embrace of a free-thinking individualistic approach to life also became manifest in his interest in science and philosophy – a course of study somewhat at odds with his family history of careers in law and the judiciary. His father Jean Baptiste Antoine Rivail was a judge.

Following the path illuminated by Pestalozzi, Rivail published his first educational text – a book aimed at children called Practical and Theoretical course in Arithmetic – at the youthful age of nineteen (perhaps twenty). As staunch an advocate for public education as his mentor, Rivail not only published a second book, Plan proposé pour l’amélioration de l’éducation publique (Proposed Plan for Improving Public Education) in 1828 but spent some of his early professional years teaching free courses in Chemistry, Physics, Anatomy, and Astronomy to the underprivileged at his home in Paris.

He earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in science as well as a doctorate in medicine. These pursuits led him to membership in a number of scholarly societies including the Historic Institute of Paris, the Society of Natural Sciences of France, the Society for the Encouragement of National Industry, and the Royal Academy of Arras. But, after a singular event, his life was about to pivot away from pure science.

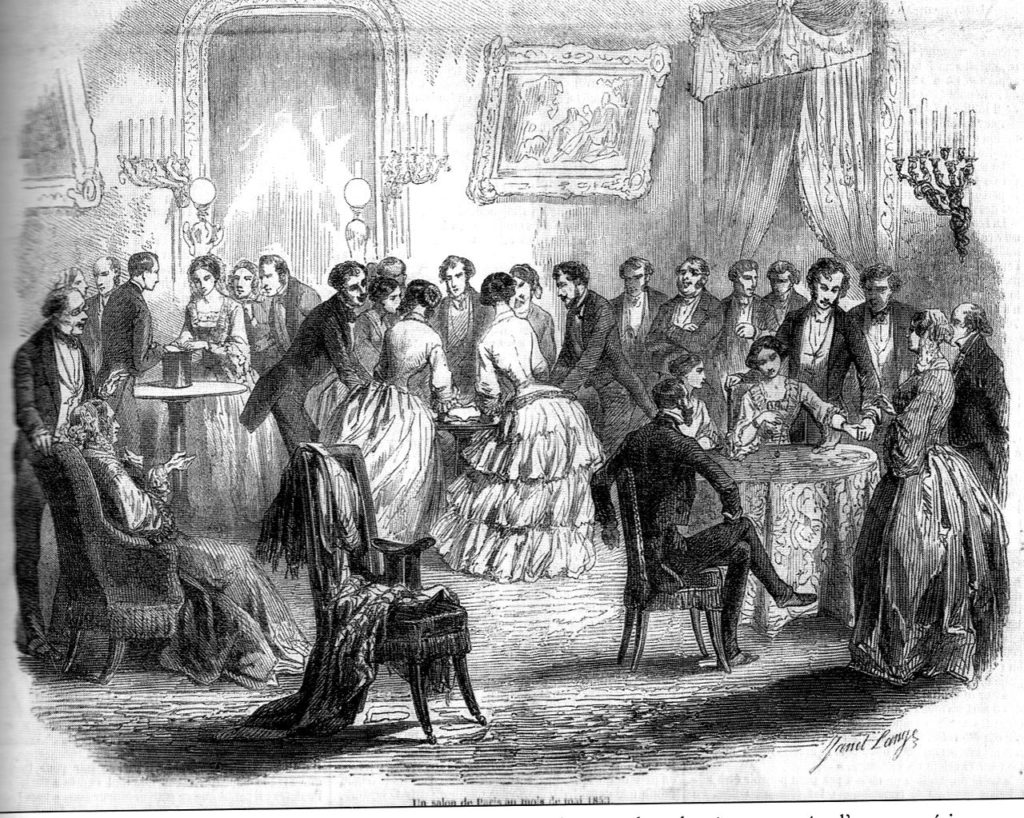

In the middle of the 19th-century the phenomenon known as table-turning (a type of séance in which questions were asked of “spirits” whose replies came by moving or tilting the table)

began to sweep across Europe and it would change Rivail’s life. It seems that he was about 50 when a M. Fortier – who is described as a “magnetizer” – introduced him to the phenomenon at the home of a Mme. Plainemaison. Rivail later claimed the demonstration left him stunned and, drawing on his background in science, he determined to undertake a thorough investigation.

He was then introduced to Julie and Caroline Baudin (sometimes spelled Boudin) teenage sisters who their parents asserted were mediums because for them the tables didn’t merely turn, they communicated psychographic messages through the girls who used a wicker basket 15 to 20 centimeters in diameter with a pencil on the end. “Putting the medium on the edge of the basket, the whole apparatus shakes, and the pencil begins to write,” Rivail would later state in The Book on Mediums. (Interestingly, the practice seemed to have gotten its start with another set of sisters Kate and Margaret Fox in Hydesville, NY.)

Over a period of 20 months, Rivail reportedly attended weekly sessions at the Baudin house. During these sessions he asked 501 questions about the universe collecting answers through the girls that he believed came from the spirits. It was also at these sessions that he asserted he met the protective spirit Zefiro. Zefiro told Rivail that they had known one another in a previous existence at the time Druids lived in Gaul and, according to Zefiro, Rivail was then called Allan Kardec.

The 501 questions and answers provided the source material for The Spirits’ Book which he first published under the name Allan Kardec in 1856 and revised in 1857. He maintained that he had published under the name Kardec at the specific direction of the spirits with whom he believed he was communicating.

To the book in which you will embody our instructions, you will give, as being our work rather than yours, the title of Le Livre des Esprits (The Spirits’ Book); and you will publish it, not under your own name, but under the name of Allan Kardec. Keep your own name of Rivail for your own books already published; but take and keep the name we have now given you for the book you are about to publish by our order, and, in general, for all the work that you will have to do in the fulfillment of the mission which, as we have already told you, has been confided to you by Providence, and which will gradually open before you as you proceed in it under our guidance.

So, from that point forward, Rivail became Kardec. Kardec himself never claimed to be a medium which might seem curious because it put him in a position of having to rely on other “mediums” to obtain the spirit communication from which his religion evolved. Conversely, because he didn’t rely on a single medium, no one could easily assert that his claims and interpretations reflected only his personal beliefs and opinions.

(Allan Kardec and his wife Amélie Gabrielle Boudet from Wikimedia.)

Kardec continued communicating with his spirits through different mediums for more than a decade. His original 501 questions and responses more than doubled and he continued recording that work into five books known as the Spiritist Codification. They served as the basis for his new religion. He died of an aneurysm in 1869 and his wife Amélie, whom he had married in 1832, carried on his work with sufficient fervor that most considered her the primary authority on Spiritism.

Although Kardec called Spiritism, “a science that deals with the nature, origin, and destiny of spirits, and their relation with the corporeal world”, it is, in essence, a theistic belief system (The Universe is god’s creation.) with at least some of its basis in Christianity. (The morality of Christ, as contained in the Gospels, is the guide for the secure progress of all Human Beings.) However, its practice is substantially different from western theistic tradition as are some of its beliefs.

To begin, Spiritism has no clergy and should be practiced, “without any external forms of worship, within the principle that God should be worshiped in spirit and in truth.” According to one website, Spiritism “recognizes that the truly good person is one who complies with the laws of justice, love, and charity in their highest degree of purity.”

But it isn’t merely honoring the memory of Spiritism’s codifier that draws tens of thousands of annual visitors to Kardec’s grave. Those reasons can be found in the set of the essential beliefs of Spiritism:

- Spirits are created simple and ignorant. They evolve intellectually and morally, passing from a lower order to a higher one, until they attain perfection, when they will enjoy unalterable bliss.

- Spirits preserve their individuality before, during, and after each incarnation.

- Spirits reincarnate as many times as is necessary for their spiritual advancement.

And, of course, its expressed on the crown of Kardec’s memorial

that can be translated to mean. “To be born, die, again be reborn, and so progress unceasingly, such is the law.”