Tito’s Legacy.

Although Tito did much good for Yugoslavia and was, in many ways, unique among communist leaders, we need to keep in mind that he was also a study in contrasts. I previously described him as a strongman dealing from a position of strength who repressed any real or alleged opponent of his own view of Yugoslavia in a way that was marked by significant violations of human rights with tens of thousands of political opponents sent to forced labor camps.

He built Yugoslavia by acknowledging a degree of respect for national identity while ruthlessly attempting to purge any seeds of ethnic or religious nationalism that threatened the Yugoslav federation. His respect for national identity was more generous with Slavs, who were free to use their own language under Yugoslav law but was not quite as generous toward ethnic Albanians for whom the presentation of ethnic identity was severely limited. Almost half of the political prisoners in Tito’s Yugoslavia were ethnic Albanians jailed for asserting their ethnic identity. And one historian stated that outside the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia had more political prisoners than the rest of Eastern Europe combined.

(More than 75 percent of Yugoslavia’s ethnic Albanian population lived in Kosovo. Although initially an autonomous region of Serbia, Tito granted Kosovo the status of an autonomous province in 1963. However, the Kosovars continually pressed for ever greater autonomy. The Serbs, meanwhile pressed for a return to more Serbian control. All of this roiled into the conflicts of the 1990s and is a topic of much greater complexity than I will address here. Kosovo unilaterally declared its independence on 17 February 2008 receiving international recognition from nine countries including the U S, the U K, and France the following day. By the time the International Court of Justice validated the 2008 declaration of independence in 2010, more than 60 countries had officially recognized Kosovo as an independent state.)

Of course, Tito’s repression wasn’t limited to ethnic Albanians. Anyone seen as anti-Titoist was threatened or imprisoned. For example, as early as 1956 Tito arrested and imprisoned Milovan Đilas – seen by many as his closest advisor and potential successor – because he criticized the regime. In the same year, Venko Markovski, a writer, Partisan, and Communist politician of Macedonian and Bulgarian descent, was arrested and jailed for writing anti-Titoist poems.

Conversely, unlike most other communist and socialist regimes, Yugoslavs were generally free to travel, and during Tito’s time Yugoslavia prospered (or appeared to prosper) more than the other European communist nations – although it could be argued that Hungary and Bulgaria fared as well or better. Sadly, as the now independent former Yugoslav republics learned, much of that apparent prosperity was built on debt rather than a stable economic foundation. After his death in 1980, it quickly became apparent that, with political instability clearly on the horizon, the country would be unable to repay the massive debt that it had amassed under Tito’s rule. Thus, in addition to the scars of the wars to come, the newly emerging nations were saddled with the expectation of repaying at least some portion of this debt. The effects of both reverberate to this day.

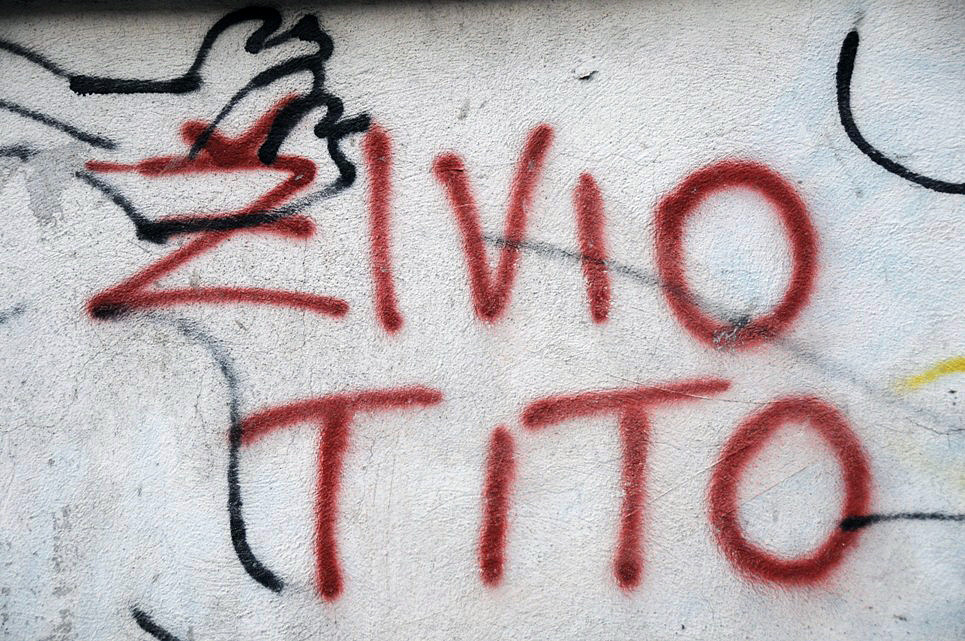

Still, many people throughout the Balkans hold a certain nostalgia for this man of many contrasts. Perhaps this is best signified by this photo of graffiti on a wall in Mostar. The photo taken by Anjči (and downloaded from Wikipedia) was shot in 2009.

Long Live Tito.

It turns out Maria is an asset to the Abbey.

Actually, in our case it was Sister Berislava one of 16 nuns who live in Lužnica – just outside the city of Zaprešic. We left Kumrovec (because there’s only so much one can do there) and stopped for lunch before moving on to see Lužnica. The building is an 18th century Baroque manor that’s now the home to the Spiritual-Educational Center Mary’s Court that’s managed by the Sisters of Charity of Saint Vincent de Paul.

The main building (seen in this photo taken from their website), was the home of a family of minor nobility of German origin named Rauch. The manor became a convent in 1925 when the Sisters of Charity bought the property from the widow of the last Baron Rauch. It transformed to its new purpose as the Spiritual-Educational Center in 2005. The nuns now live in a newly constructed building on another part of the property. As an aside, the sycamore tree in the photo was planted in the 17th century before the main house was built.

Inside, Sister Berislava showed us a stairway with the year 1761 (the date of construction) engraved in the top step

while sharing with us the history of the order there. Although all their public charitable and educational work ceased during communism, the basic story is that the sisters refused to leave the convent when the Partisans wanted to evict them and claim the estate for the state. Wary of creating martyrs, they let the sisters stay and there they lived quietly until Croatia declared its independence.

While the castle and grounds are pretty, I couldn’t discern any particular reason for visiting there at the time. As I began writing this entry more than two months after our visit and after listening to my recording of Sister Berislava’s tour, I remained uncertain. However, because I like this blog to be as full and informative an accounting as I can reasonably produce, and because I thought this place might have some significance I missed, I visited the Spiritual-Educational Center Mary’s Court website.

The English version has a link to the history page but no text. So, my next step was to go to the Croatian language page where I found a brief history that I copied and pasted into Google translate. While this, too, failed to produce any real historical significance, it did bring a smile to my face.

Near the beginning of our visit, Sister Berislava explained how the manor came to be named Lužnica. She told us that it’s a historical, geographical name coming from a small stream where people washed their clothes using ashes as soap. This left the stream full of ashes and that the word for ash in the local dialect is lug. So a stream full of ashes became Lužnica. My smile arose because every time Lužnica or some variant appeared in the Croatian half of Google’s translation, the English equivalent was ‘liquor.’ You can try it (copy and paste) if you want. Here’s the Croatian: Dvorac Lužnica. (Note: when I updated this post in 2023, the new translation is ‘leach’.)

Going green in Zagreb.

We returned to Zagreb late in the afternoon and had time to explore a bit more of the city before anyone had any thoughts of eating dinner. The afternoon weather was mild so Pat, Diane and I thought a leisurely stroll through a green area might provide a pleasant diversion. We decided to visit the Botanical Garden which was a short walk from the hotel. I’d walked past there the day before but the garden closes early on Tuesday.

Founded in 1889, the garden manages to present a lot of variety with over 10,000 plant species in a relatively small space. I’d guess it’s about three city blocks long by one block wide and it makes up part of the bottom of Zagreb’s Green Horseshoe seen in my first post about our arrival.

We entered from Mihanoviceva Street (Photos from Croatia.org):.

And I’ll add some random downloaded photos to give you some idea of what it looks like:.

and.

finally.

A large group of us went out to a late dinner at a restaurant that Al and Linda (who were the trip’s gourmands) chose. The restaurant was crowded and, faced with a choice of sitting outside or on the lower level, we chose the latter because a light rain had begun falling. The food was quite tasty but the service a little spotty. At times, it seemed the staff had forgotten us. After dinner, Trina and I walked over to an ice cream shop that Damir had highly recommended. I had two scoops but it wasn’t my favorite ice cream of the trip. That I had in Ljubljana. Trina and I ate our ice cream as we walked back to the hotel in a steady drizzle.

Tomorrow, we’ll leave Zagreb on our way to Istria with a stop in one of the most beautiful spots in all of Croatia, the UNESCO World Heritage site of Plitvice Lakes National Park. See you then.