Despite the elections, it’s a bit of an understatement to say that the nascent Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia was far from being a stable country let alone some sort of federal democratic republic.

Maybe not quite Fifty Ways but 0ne breakup after another

Number 1 – The Catholic Church

The seeds for the first breakup were sown in June 1945 when Tito met with Aloysius Stepinac who was the president of the Bishops Conference of Yugoslavia (HBK) to discuss (but not agree on the status of the Catholic church in a newly formed Yugoslav state. In September 1945, still under Stepanic’s leadership, the HBK released a letter filled with alleged Partisan war crimes. A year later, the Yugoslav government put Stepanic on trial for assisting Ustaše terror and for supporting forced conversions of Serbs to Catholicism. After they sentenced the bishop to 16 years in prison, the Vatican retaliated by excommunicating Tito and the Yugoslav government.

Number 2 – Cracks in the Soviet Bloc

In the years immediately following the war, Tito was widely considered as very loyal to Stalin and Moscow because of his strong commitment to orthodox Marxist ideas that he enforced through harsh and repressive measures against dissidents including arrests, show trials, forced collectivization of agriculture and industry, and the suppression of churches and religion. The truth isn’t quite so binary. The alliance between Stalin and Tito was more one of convenience and it was viewed warily by both leaders. Stalin thought Tito too independent while Tito saw the Russians as trying to gain undue influence in internal Yugoslav politics by claiming too much credit for the role the Red Army played in liberating the country.

By May 1948, Tito modeled an economic plan for Yugoslavia quite independent of any input from Moscow. Over the next year, a series of tense diplomatic exchanges nearly escalated into an armed conflict as Hungarian and Soviet forces massed on the northern Yugoslav frontier. In 1949, the Cominform (an official forum of the international communist movement in post-World War II Europe and originally headquartered in Belgrade) expelled Yugoslavia and moved its headquarters to Bucharest.

Stalin confidently thought that Tito and his government would collapse once it became clear that he had lost Soviet support. He miscalculated. He’d underestimated the loyalty that Tito had built through the success of the Partisans. Tito, who survived a number of assassination attempts that Stalin had instigated,

began a near decade long effort to repress any real or alleged opponent of his own view of Yugoslavia – a period marked by significant violations of human rights with tens of thousands of political opponents sent to forced labor camps.

Number 3 – Allies / Shmallies

While the feud with Stalin deepened, Tito’s independent nationalist side also manifested itself with the western allies and undermined the foundation of that relationship as well. Remember, the western allies had formally recognized the JNA in the fight against the Axis. Because he’d played such a pivotal role with the Partisans, Tito was a strongman dealing from a position of strength.

The first dispute between Tito’s Yugoslavia and the western powers came over the status of Istria. This small peninsula has had quite a volatile history which I’ll discuss briefly when we visit there in a few days. For now, the relevant point is that Istria became part of Yugoslavia after the end of the Second World War. However, conflict over the status of Trieste remained a sticking point. The Yugoslavs wanted to incorporate the city under their control. The allies were opposed to that. After several armed clashes between Yugoslav and allied forces from 1945 to 1947, Tito finally reached an agreement with British Field Marshal Harold Alexander to withdraw Yugoslav troops from Trieste and it eventually became part of Italy.

Meanwhile, the rift between Tito and the Soviet Union deepened. This split allowed Tito to turn for aid to the United States Economic Cooperation Administration (which administered the Marshall Plan). However, Tito, leveraging his local strength and political savvy, managed to avoid many of the conditions usually attached to this aid and never formally aligned with the West.

For example, in 1950 Tito helped draft a law introducing profit sharing and workplace democracy in previously state-run enterprises. This then became direct social ownership by the employees promoting the notion that this law on self-management was the basis of the entire social order in Yugoslavia. Tito also openly supported the communists in the Greek Civil War while Stalin had agreed with Churchill not to pursue Soviet interests there.

After Stalin died in 1953, Tito took two additional steps that continued to play East against West. First, he refused Nikita Khrushchev’s invitation to come to Moscow to discuss normalization of relations. Second, he began to accept aid from the Council for Economic Assistance (known by the acronym COMECON) which was the Soviet attempt to counter the Marshall Plan. From all of this eventually arose

The Non-Aligned Movement.

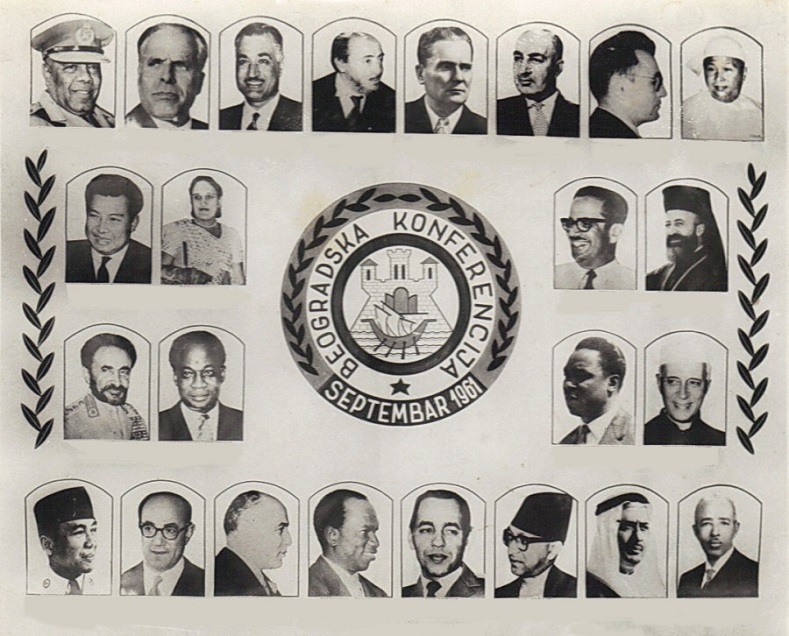

In September 1961, spearheaded by the Initiative of Five – for the five leaders (Tito, Jawaharlal Nehru, Gamal Abdel Nasser, Sukarno, and Kwame Nkrumah) who created the impetus for it – Belgrade hosted the first Conference of Heads of State or Government of Non-Aligned Countries which became known as the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM). It’s five basic founding principles were:

- Mutual respect for each other’s territorial integrity and sovereignty

- Mutual non-aggression

- Mutual non-interference in domestic affairs

- Equality and mutual benefit

- Peaceful co-existence

Tito was elected its first Secretary General and he saw the group (it was never a formally established organization) as a ‘third way’ for countries interested in staying outside of the East-West divide.

Spurred by Tito’s initial leadership, in which the Yugoslav leader gave frequent public speeches that reiterated a policy of neutrality and cooperation with all countries during the Cold War period, many countries in the NAM enjoyed practical, if not cordial, relations with both East and West. This was particularly true for Yugoslavia in terms of its relations with the Soviets, the U.S., and Western Europe.

Considering the often incongruous, disparate group of leaders who would succeed Tito as Secretary General – such as Suharto and Nelson Mandela – the effectiveness of the NAM throughout the Cold War is yet another indication of Tito’s political skills.

There’s more history to come in part three.