The first siege of Mostar: April 1992 – June 1992.

During the wars of the early nineties, Mostar held the rather dubious distinction of being a besieged city on two different occasions by two different armies. Although none of the former Yugoslav Republics had officially held independence referenda, the Yugoslav National Army (JNA) – forces that would become the army of Rump Yugoslavia began arming Bosnian Serbs in the fall of 1990. The tacit support and strong ethnic rhetoric emanating from Belgrade, particularly through Slobodan Milošević, who talked among other things of a Greater Serbia, prompted Serbs in B&H to declare several so-called Serbian Autonomous Regions.

Slovenia was the first Republic to claim its independence and broke away with relatively little fighting. Croatia followed soon after with its own independence referendum and by July 1991 fighting in the Croatian War of Independence began in earnest. Attempting to counterbalance the JNA arming Serbs in Bosnia, and anticipating a possible attempt by the Serbs and their allies to spread their war with Croatia into B&H, the Croatian government under Franjo Tuđman began arming the Croat (Catholic) population in the Herzegovina region. In an alliance of convenience, they also began arming Bosniaks in the region.

Tuđman proved prescient. JNA and Bosnian Serb paramilitary units began launching attacks on Croatian territory late in the summer of 1991. The Croatian leader responded by employing a clever delaying tactic. He repeatedly signed numerous cease fires negotiated by foreign diplomats buying him time to build the Croatian army from seven brigades to 64 brigades in a span of months. Meanwhile, the president of B&H, Alija Izetbegović, tried to maintain a neutral stance in the fighting between the JNA and the Croats and announced he wouldn’t take defensive measures against a probable attack by the JNA and Bosnian Serbs.

By November 1991, the largest political party of Croats in B&H, the HDZ BiH, declared the autonomous Croatian Community of Herzeg-Bosnia. It was never recognized internationally and in 2001 the ICTY ruled that that Herzeg-Bosnia was founded with the intention to secede from Bosnia and Herzegovina and unite with Croatia. Some evidence supporting that conclusion came from documents showing that though it claimed it had no intent to secede, Tuđman was telling Bosnian Croat leaders that from the perspective of sovereignty, Bosnia-Herzegovina had no prospects. His policy was to support B&H’s sovereignty until such time as it no longer suited Croatian interests.

In March 1992, B&H held its independence referendum (which, you remember, the Bosnian Serbs boycotted). The two ethnic groups that did vote approved the referendum by an overwhelming majority and Izetbegović declared B&H’s independence from Yugoslavia on 3 March 1992. Because it suited them, Croatia recognized the new country the same day.

A month later, Bosnian Croats joined by some Bosniaks formed the Croatian Defense Council (HVO). The formation of this force then allowed Izetbegović to concentrate the Bosnian forces in defense of Sarajevo while leaving the defense of the rest of the non-Serbian controlled territory to the HVO. The JNA launched its first attack on Mostar on 6 April 1992 and by the middle of the month had surrounded the city and captured many strategic locations. Mostar remained under siege until June.

Before and during this time, Tuđman or his representatives were secretly (or perhaps not so secretly) meeting with both Radovan Karadžić, president of the self-proclaimed Republika Srpska and Slobodan Milošević, to discuss (according to some reports) the ultimate partition of B&H. Despite reaching a tentative cease fire agreement on 6 May, the two sides couldn’t agree on the disposition of Mostar. The Croats wanted complete control of the city while the Serbs claimed the city east of the Neretva River.

The Croats launched a secret counterattack on Mostar on 7 June and by 13 June had pushed all the Serbian forces to the east side of the river. The retreating Serbs destroyed two bridges spanning the Neretva but left a damaged Stari Most standing. By 21 June, all JNA forces had been pushed out of Mostar.

The damaged Old Bridge stood as the only crossing of the Neretva in Mostar but many notable buildings in Mostar were severely damaged or destroyed during the Serbian siege and Croatian counterattack including several churches, 12 of the city’s 14 mosques, the Franciscan Monastery, and the Bishop’s Palace that held a library collection of over 50,000 books.

Taking a breather – A few words about my actual travels.

Before I get too deeply into the second siege of Mostar, which will be at least as dark and confounding as the first, I’ll tell you a bit more about our time there and share a cluster of pictures because I only have a few days of photos left to share. I have few complaints that our time in Mostar would be briefer than it was in Kotor because it was a stop en route to Sarajevo and was planned mostly to be a lunch break and to provide the opportunity to see one of the true architectural wonders of the area. During our stop we would have time to do a bit of shopping at the open market on the Stari Grad (Bridge Street)

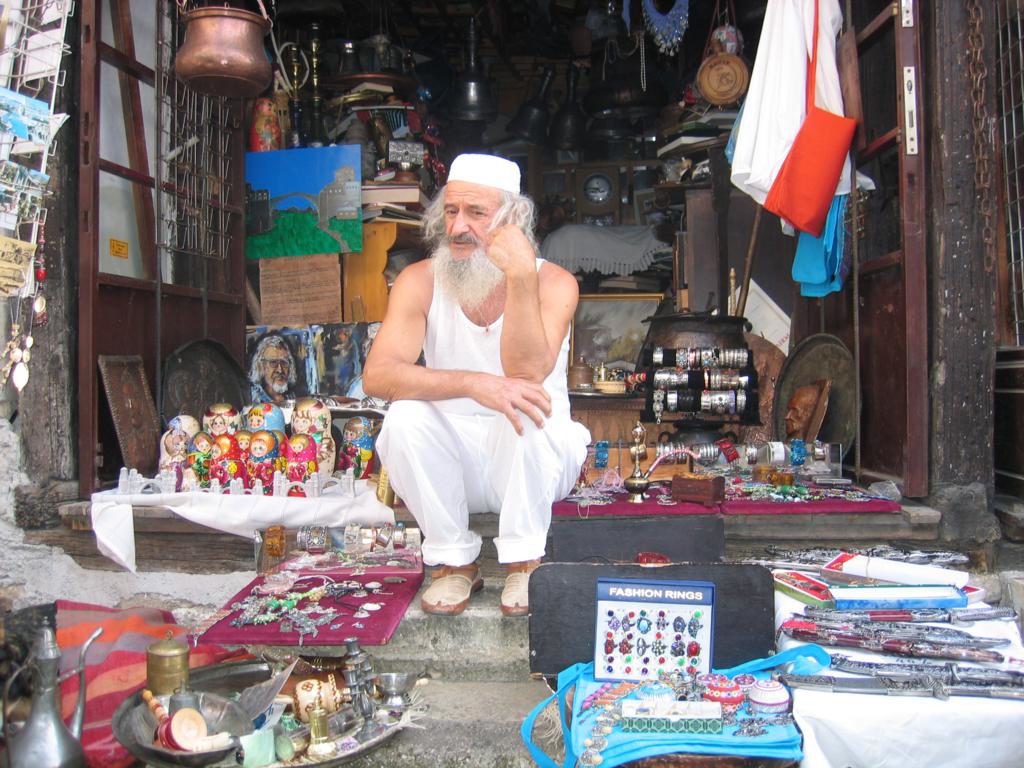

or sneak a photo of an interesting character peddling his wares.

We had very little time to shop before our group lunch at Sadrvan – a restaurant quite close to the Old Bridge – that claims “It’s where tradition reigns.” The staff dresses in traditional costume and the meal was reputed to be one that is traditional to the region. (Mine wasn’t because I don’t eat mammals.) We had a bit more time after lunch to take photos of the bridge (above) or from it looking east:

or northeast

Or even get a sense of why the city is vulnerable to a siege.

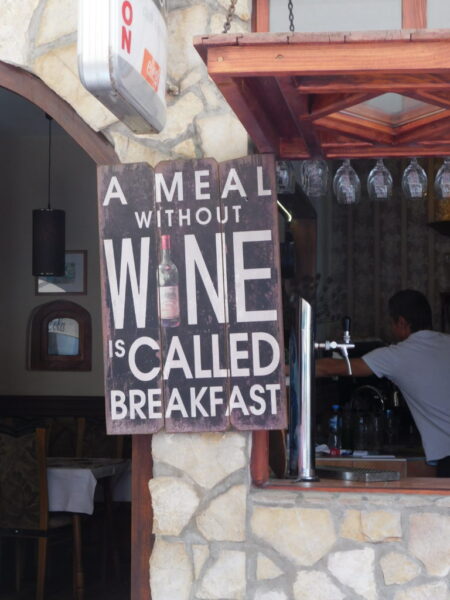

If we stayed observant, we also might spot an amusing sign (that the Hungarians would later disprove).

Or buy another new hat.

After lunch and those small adventures, we boarded the bus to complete our journey to Sarajevo, the capital of B&H. My scanty notes and photos prompt no remarkable memories for this segment of the ride. Much of the drive followed the course of the Neretva River and probably lasted a bit over two hours.

Now I’m going to ask you to envision yourself riding with us through the now peaceful, hilly, and green countryside between Mostar and Sarajevo because the story I’m about to relate in the next post is anything but peaceful and serene.