Okay, so maybe this isn’t the best pun possible but it’s the best I could do with minimal effort. Really, to approximate the Portuguese pronunciation of the city it would sound something like kuhs-KYSH where the first vowel sounds like the vowel in soot and the second like the vowel in ice or fight.

A little pre-history and a little history

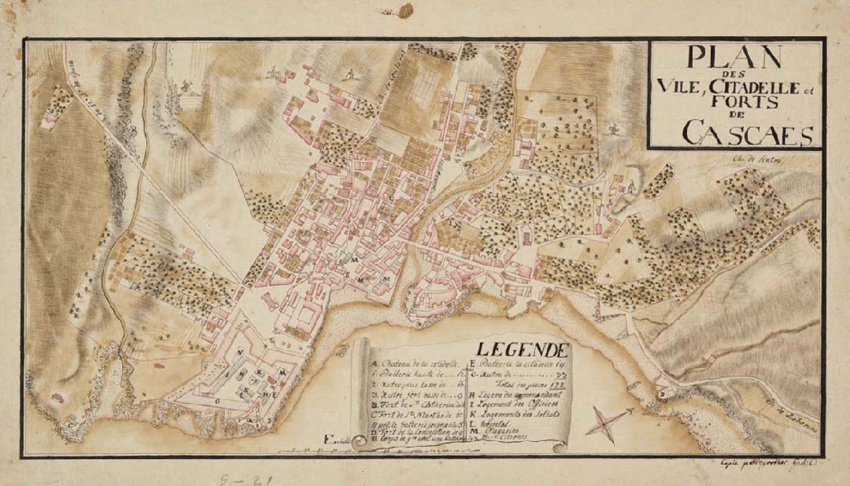

As I noted in the initial post for this series, Cascais is something of a bedroom exurb of Lisbon. Although considerably less costly than in Lisbon, real estate in Cascais is relatively expensive for Portugal so the people who live there are likely to live away from the coast and the tourist areas. For much of its settled history, the city and surrounding area was a relatively quiet fishing village that supplied much of the fish and seafood for Lisbon. In fact the most likely derivation of the town’s name is from the expression ‘monte de cascas’ meaning pile of shells.

(From ResearchGate.net)

But let’s go back a little further in time. While there’s some evidence of late Paleolithic Age human habitation in the area, the first permanent settlements appear in the Neolithic with the best evidence provided from the natural grottoes where bodies were buried along with some sort of offerings.

But these appear to have been isolated communities so let’s take a great temporal leap forward to see that a combination of archaeological ruins and many place names indicate the presence along the coast of Romans, Visigoths, and Moors. The Roman Empire reached the Iberian peninsula sometime in the third century BCE but it wasn’t until the early first century that they reached the west coast. Over time, Visigoths and Moors eventually followed the Romans and these three groups ruled the area from the first through fifteenth centuries.

Cascais became a popular seaside resort in the latter half of the 19th century when King Luis I (known as ‘the Popular’) made the town his summer residence. He went on to equip the citadel (inside of which you’ll find my hotel) with the country’s first electric lights.

(Luis I – Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain)

The presence of a royal residence helped change a relatively quiet fishing village into a cosmopolitan address because, of course, once the royal family moved in, much of Portuguese nobility and other elites soon followed and with them the construction of many small palaces and other opulent homes. The royal family spent summers there until 1908 when King Carlos I was assassinated that year in Lisbon.

In 1896, Carlos I (know variously as the ‘Diplomat’, the ‘Oceanographer’, and the ‘Martyr’) installed the first oceanic laboratory in Portugal whence he personally led at least a dozen experiments. He was known for his love of the sea and despite being assassinated, Carlos I today has a monument outside the cidadela

(dedicated in 2008 in the centennial year of his assassination) and the maritime museum in Cascais is also named in his honor.

Looking into the Mouth of Hell

In my initial post, I mentioned that I didn’t visit Nazaré – a place that’s become famous among surfers for its 20 – 30 meter waves. Nazaré is 140 kilometers or so north of Cascais and while the local geography is different enough to prevent the formation of those massive waves, the power of the Atlantic isn’t significantly lessened. I needed to walk less than two kilometers from my hotel to reach the spot called Boca do Inferno – literally “Mouth of Hell.”

The coastline to the north and west of the city is a carbonate platform of sedimentary limestone, mudstone, and sandstone. At one time this was a cave. However, the erosive force of the Atlantic waves collapsed it into the arch and chasm formation we see today. The scene was unusually calm during my visit.

Apparently the most violent storms occur during the winter months when the rushing water explodes upward in volcano like fashion.

Now, while this coastline is certainly dramatic with a certain stark beauty there’s another reason to at least give it a look even if your visit doesn’t coincide with seeing the pounding surf. It’s time to learn a little about

Aleister Crowley.

Four years ago, I posted an entry on this blog entitled Père-Lachaise Chronicle – l’édition Kardec wherein I recounted the life of Hippolyte Léon Denizard Rivail who, under the name Allan Kardec, founded and codified the religion known as Spiritism. Although Kardec died some six years before Aleister Crowley was born, they might be considered, in at least one way, kindred spirits.

Atlas Obscura describes Crowley as a “famed astrologer, magician, and occultist.” Wikipedia adds that he was an “English occultist, ceremonial magician, poet, painter, novelist, and mountaineer.” A child of some wealth, Crowley was rebellious from an early age and rejected the fundamentalist Christian Plymouth Brethren faith of his parents.

More germane to my associating him with Allan Kardec is that Crowley (seen here in a photo from 1912)

(Wikipedia – Unknown – Book 4, Part 2 (1912). Originally uploaded to Commons by user Dnaspark99)

founded a religion called Thelema from the Greek word for will. Crowley believed in what he termed Magick which he defined in his book Magick in Theory and Practice as “the Science and Art of causing change to occur in conformity with Will” and, much like Kardec, described it elsewhere as a practice that involved “getting into communication with individuals who exist on a higher plane than ours. Mysticism is the raising of oneself to their level.”

Much as Kardec asserted that he received The Spirits’ Book from a protective spirit called Zefiro, Crowley, while on his honeymoon in Cairo in 1904, claimed to have been contacted by a supernatural entity named Aiwass from whom he received The Book of the Law. This then became a sacred text that served as the basis for Thelema. Crowley’s purpose was to lead his followers into the Æon of Horus and The Book of the Law declared that its followers should “Do what thou wilt” and seek to align themselves with their True Will through the practice of magick (sic).

His association with Cascais and, more particularly, Boca do Inferno, came in 1930 where, for reasons I have been unable to uncover, he faked his death by suicide. He was abetted in this hoax by the great Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa whose interest in occultism had prompted him to correspond with Crowley. Pessoa aided Crowley by delivering his suicide note to local newspapers, explaining the note’s Thelemic symbols, and clarifying Crowley’s defective Portuguese. Crowley resurfaced three weeks later in Berlin and died in England in 1947 at the age of 72.

Although I didn’t see it, Atlas Obscura assures me that,

Today, there is a small white plaque mounted on the rock commemorating the event. It tells the story of the pseudocide and provides the text of Crowley’s suicide note: “Não Posso Viver Sem Ti. A outra ‘Boca De Infierno’ apanhar-me-á não será tão quente como a tua” which translates roughly to “Can’t live without you. The other mouth of hell that will catch me won’t be as hot as yours.”