I Call it Pretty Music – part 4

Before we go.

Although he was only there for a brief time, Berry Gordy put his experience working at Ford to good use in building Motown. In his autobiography To Be Loved, Gordy wrote, “At the plant, the cars started out as just a frame, pulled along on conveyor belts until they emerged at the end of the line… I wanted the same concept for my company, only with artists and songs and records. I wanted a place where a kid off the street could walk in one door an unknown and come out another a recording artist – a star.” The challenge, of course, was finding the path to adapting and modifying those methods to an industry where judgement on the final product was considerably more subjective.

The biggest adaptation Gordy made was likely his decision to keep every aspect of the business in-house. In the previous post, we saw how he applied this to artist development and production in overseeing the creation of the Motown look and sound but his control went far beyond that. Motown was almost completely self-sufficient.

The Motown assembly line started with its team of writers and producers all of whom were led by Gordy and guided by one of his key songwriting principles – capture the listener’s attention in the first 10 seconds of the song, or start over. To foster their creativity, Gordy also made certain that his artists had access to Motown’s studio twenty-four hours a day seven days a week.

While the label’s A&R staff was primarily responsible for finding and identifying new talent, as we saw from Bobby Taylor’s discovery of the Jackson 5, everyone affiliated with the label was encouraged to be a part of this team.

Gordy also served as the artists’ booking agent and he initiated the Motortown Revue Tours. This served as something of a baptism by fire for his artists. As part of his quality control (another crucial step in his process) Gordy would frequently have different artists record the same song and it was at the legendary quality control meetings that people would vote on best version. The winner would be the one that was ultimately released. This fostered a spirit of friendly competition between the musicians and singers that also carried over onto the Revue Tours. As each act performed a short set of songs, their goal was to make it harder for the following act to match them. Gordy believed that competition made champions.

And that competition happened every week at Motown’s corporate headquarters and the quality control meetings mentioned above. Artists and producers would put forth arguments in favor of their records and, according to reports, these sessions could get quite heated. Gordy would frequently pose a question along the lines of, “If you were hungry and only had a dollar, which would you buy – a hot dog or this record?” If the hot dog won, the record was returned whence it came for more work and improvement.

[Image from imdb].

Among the label’s biggest hits that missed the first cut were Marvin Gaye’s What’s Goin’ On and I Heard It Through the Grapevine. The latter was eventually recorded successfully by both Gaye and Gladys Knight and the Pips.

In order to assure his records received sufficient airplay, Gordy established several different record labels to compliment Motown and Tamla. These included Gordy in 1962, Soul in 1964, Mowest in 1972, and Hitsville in 1976. Their purpose was to circumvent a policy that arose after the Payola scandal of the 1950s that limited the amount of airplay given to the same label in a certain period of time.

Just how successful they became is evidenced by the fact that the formula worked. Between 1961 and 1971, Motown released 535 singles in the U S. Of these, 357 either made the R&B charts and/or the pop charts. Twenty-one topped the Hot 100 and 110 reached the top ten. In and industry where it’s considered successful for a label to have 10 percent of its songs reach the charts, Motown’s releases had an all but unfathomable 75 percent success rate on that metric. Motown was, indeed, as Berry Gordy’s sign declared, Hitsville U.S.A.

To every thing…

The sixties and seventies in the U S were a time of turmoil and change with respect to many issues not the least of which was race relations. Gordy had inventively and meticulously built his enterprise around a slick, urban, identifiable sound combined with specifically crafted public images for his stable of artists. Still, while maintaining a certain degree of caution, it’s likely no one in the industry was more aware of the challenges faced by African-Americans in every walk of life so, under the right circumstances, neither he, nor his acts shied away from participating in that era’s civil rights struggles.

Gordy’s association with the civil rights movement must be viewed through the lens of his accomplishments as a businessman which is what he was first and foremost. Overcoming considerable barriers he demonstrated that a Black-owned record company could become as successful as any other in the industry and that Black songwriters and performers deserved a place at the top of popular music.

Although he didn’t want to risk losing his growing White audience, Motown still released two albums of speeches by Doctor Martin Luther King, Jr. – though Gordy probably perceived his decision to do so differently than he would have had it involved one of his artists. In his book Just My Soul Responding, Brian Ward wrote,

Gordy, the most successful Black entrepreneur of his generation and a living embodiment of Black integrationist aspirations, was always reluctant to allow his artists to embrace potentially controversial subjects that may jeopardize their white audience. Gordy was a businessman, though, and if he thought political consciousness could be successfully monetized, he’d allow it.

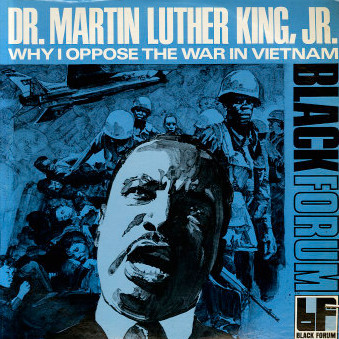

Thus, Motown acts played at events that raised funds for African-American causes and, after Doctor King was assassinated in 1968 Gordy had discussions about how to move Doctor King’s dream forward with his widow Coretta Scott-King. This led to Gordy establishing the Black Forum in 1970 – a Motown imprint that focused on the spoken word. Its initial release was an album that featured two recordings of King’s speech “Why I Oppose The War In Vietnam”.

Between 1970 and 1973, Black Forum issued a dozen LPs. The project went silent for nearly half a century but was recently revived with Jamila Thomas co founder of #TheShowMustBePaused initiative as its Vice-President Artist Marketing.

But could it have been more?

There can be little doubt that the $61 million Gordy received from MCA in 1988 is a significant sum. But, in light of the label’s historic and historical success, it seems a bit undervalued.

Although he often referred to the love between the label and its artists, Gordy also had policies that can best be described as self-serving. Keep in mind the way that everything about Motown was kept in-house. This allowed Gordy to write contracts that favored the label in every circumstance. He never allowed industry regulatory groups such as the RIAA to review his books and the artists themselves could examine them no more than semi-annually. If an artist signed as a performer and a writer, any costs incurred in preparing his or her records could be charged against the artist’s songwriting royalties.

As early as 1967, tension was flaring between Gordy and his most successful songwriting team – Holland, Dozier and Holland over charges of unpaid royalties. The trio eventually left and started their own labels Hot Wax and Invictus.

Although Stevie Wonder remained exceptionally loyal to the man and the company that gave him his start, he also negotiated a unique contract later in his career that provided him more artistic freedom. (Although he might have been the apple of Gordy’s eye, even Motown couldn’t stay forever in his heart. He left the label in 2020.)

Other relationships such as those with the Jacksons, Michael Jackson, the Isley Brothers, and even Diana Ross (with whom Gordy rather famously had an extramarital affair) chafed under Berry’s control and became strained causing them to eventually leave the label. Perhaps if Gordy had been fairer financially and allowed his artists more freedom of expression, they would have remained with Motown and the company Gordy sold would have had a significantly higher value.

While all of the history I’ve reported didn’t spring from my visit to the Motown Museum, it sparked the research and, for me, filled my ears with musical memories that made writing about it a pleasure. Here’s where you can see the remaining photos from my visit to Hitsville, U.S.A.

Até a próxima.

-

It’s just a shot away – Prizren

March 6, 2026 -

Some things looking better, baby – Getting into Kosovo

March 4, 2026 -

Here, where the sky is falling – Kukës

March 2, 2026 -

That’s when we fall in line ’cause we got Berat

February 27, 2026 -

Walking on the big stuff – a climb to Tragjas

February 25, 2026

2 responses to “I Call it Pretty Music – part 4”

“Although he often referred to the love between the label and its artists, Gordy also had policies that can best be described as self-serving. Keep in mind the way that everything about Motown was kept in-house. This allowed Gordy to write contracts that favored the label in every circumstance. He never allowed industry regulatory groups such as the RIAA to review his books and the artists themselves could examine them no more than semi-annually. If an artist signed as a performer and a writer, any costs incurred in preparing his or her records could be charged against the artist’s songwriting royalties.”

The true essence of Gordy. Absolute control with the intent of stealing millions of dollars from the artists under his labels. Yet he’s not the only one to take advantage. Record labels and agents have been screwing artists since the advent of the music industry. Relates back to my comment on your first post.

Excellent series TC. Really enjoyed it.

Thanks, MK.