More than just the hits. How Berry Gordy, Jr. made the Motown miracle

In just under 30 years Berry Gordy, Jr. had taken the $800 (about $7,650 in 2023 dollars) loan from his family credit union and turned it into a successful enterprise that he sold in 1988 to MCA for $68,000,000 (about $176,000,000 in 2023). He achieved this remarkable return on investment despite the myriad challenges faced by a Black owned business.

Even today , you have to go all the way to the top five on this list of the 20 largest Black owned businesses to find one with revenue exceeding one billion dollars. With revenue a bit over $7.2 billion, Robert Half International slots into the final spot on the Forbes 500 list of the largest publicly traded businesses in the U.S. meaning no Black owned business is within sniffing distance of this list.

Although there was a different energy surrounding race relations in the sixties and early seventies than exists today, we need to keep in mind that it wasn’t until 1954 in the famous Supreme Court Ruling in Brown v. Board of Education, that a public policy of segregation became illegal. Yet, by 1965, barely six years after its inception, Gordy’s Motown was, according to at least one report, the richest corporation in African-American business history to that time. In this framework, what Gordy accomplished at the urging of his friend Smokey Robinson seems to be nothing short of a miracle. I think it’s worth looking at how he did that.

And early absence of color

Before Berry Gordy, black musicians and songwriters achieved success in three principal genres of music: blues, jazz, and R&B. But their successes were largely limited to the African-American community. Some artists could crossover when, following Benny Goodman’s integration of his combos and big band, they were part of a larger white ensemble but venues and audiences remained generally segregated.

(The 2008 play Marilyn and Ella dramatizes the friendship between Ella Fitzgerald and Marilyn Monroe. The play’s climax comes in 1955 when Monroe convinces Charlie Morrison – the owner of a prominent LA nightclub called the Mocambo – to book Fitzgerald but only by agreeing to attend every performance jumpstarting Fitzgerald’s entry into the American mainstream.)

Of course, White artists had no issues covering (some would say appropriating) songs written and performed by Black artists. Think of Pat Boone’s recordings of songs like Ain’t That a Shame (F ats Domino), Long Tall Sally, or Tutti Frutti (both by Little Richard), or Big Joe Turner’s Shake, Rattle and Roll covered by Bill Haley and His Comets, or Elvis Presley remaking Big Mama Thornton’s Hound Dog just to name a few.

While Motown had early success with songs like Money (That’s What I Want) and Shop Around, Gordy knew that real money could be made only by getting his songs and artists into the mainstream. Thus, he actively employed strategies to allow his artists to cross over onto the pop charts. A look at his early album covers reveals one of them.

If you recall also the cover of the Martha and the Vandellas album from the previous entry, think about what they have in common. Or what they both lack – which is any images of the artists. Gordy was also parsimonious in releasing carefully filtered details of the performers’ biographies. His plan was to have the public decide whether they liked the music on the basis of the songs and the performances alone. He wanted to create songs that he described like this, “Whether you were black, white, green or blue, you could relate to our music.”

There was more to it than the music

Gordy knew he would have to do more than create good or even great music to expand and sustain his success and, more importantly, to break the barriers that segregated Black artists from crossing over into the pop charts. Everything associated with his enterprise would be become identifiable and iconic. There would be a Motown look, Motown moves, and, most importantly, the Motown sound.

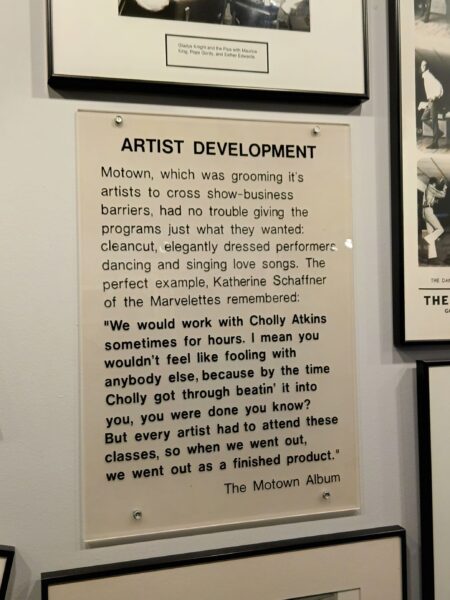

Assisted by writer and producer Mickey Stevenson, Gordy established a first of its kind mandatory development program for all Motown artists. He hired people like Maurice King – who had worked with Billie Holliday – to serve as the chief rehearsal and musical director, Cholly Adkins of the dancing duo Coles and Adkins to serve as choreographer, and Maxine Powell, who had become successful through the Maxine Powell Finishing and Modeling School, to teach personal development and growth along with proper etiquette.

Powell believed that if you worked on what’s on the inside, it would show up on the outside, and that made you more dignified, more graceful. She once said, “Some of them were from the projects, some were using street language, some were rude and crude. With me, it’s not where you come from, it’s where you’re going.”

There was certainly disbelief when Powell told them she was preparing them to perform in front of and to meet kings and queens. But then,

as Mary Wilson related above, it happened.

As for Cholly Adkins, whom Powell worked with to assure that the dance moves were ladylike, he was apparently quite a taskmaster. In this photo you can read how Katherine Schaffner of The Marvelettes recalls those sessions.

Finally, the Motown sound

The Motown sound is characterized by several readily identifiable elements – most notably and prominently – its backbeat. One music historian wrote that there’s not a lot of blues in Motown’s rhythm ‘n blues but there’s heaps of rhythm. The idea was to imbue these short often pithy compositions, with front-loaded choruses written for radio that were backed by propulsive and highly danceable rhythms.

Motown’s reverb effect represents another unique aspect of the Motown sound. Using the company’s makeshift echo chamber in the attic above 2648 Grand Boulevard, engineers jerry-rigged a method to pick up vocals from Studio A in the basement. Perfection of sound was never the intent. Rather, it created a character that not only helped shape Motown’s iconic sound but also was all but impossible for its competitors to duplicate.

(The museum has cut a hole in the ceiling leading to the attic so touring visitors can stand beneath it, belt out their favorite Motown song, and hear how they might have sounded.)

And finally, of course, there were the Funk Brothers – the rhythm section that appeared on most of the company’s records. While not every musician who ever played for Motown is considered a member, Paul Justman’s 2002 documentary Standing in the Shadows of Motown identifies 13 players who have since been awarded a Lifetime Achievement Grammy Award, a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, and been inducted into Nashville’s Musicians Hall of Fame. As the documentary noes, “By the end of their phenomenal run, this unheralded group had played on more number one hits than the Beach Boys, the Beatles, Elvis, and the Rolling Stones combined which makes them the greatest hit machine in the history of pop music.”

It was the Funk Brothers who provided Gordy’s sought after equal opportunity for all to sing, dance, and clap their hands. But while Gordy’s business model was unique in the industry and his carefully calculated balance of competition and affection elicited a remarkable level of camaraderie and loyalty between the artists and the label Motown wasn’t a utopia as we’ll see in the next, and final entry.

I’ve never seen the Mary Wilson video. Learned a lot so thanks for sharing.

👍