Humans arrive in Russia (Moscow and Me supplement two)

A never ending story of perpetual surprise.

Providing you, dear reader, even the limited detail these entries contain always requires research usually guided by a sense of knowing the questions I want answered. The joy of the journey, however, arises when my general knowledge has left me unprepared for some of the surprising paths I’ve had to travel to discover these histories of our rare third rock and of our species. This was the case when I started my investigation of humans arriving in western Eurasia.

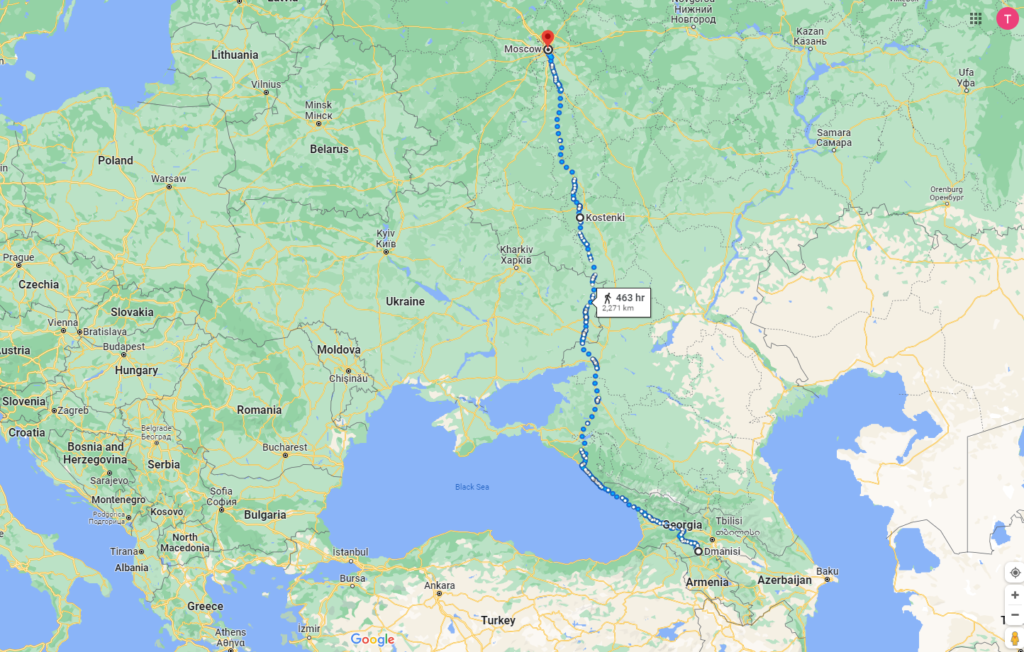

There are two sites of particular interest. The first and most surprising involved the discoveries at Dmanisi a medieval town some 90 kilometers southwest of Tbilisi.

[Screen Capture from Google maps.]

The second discovery, which should have been less surprising, happened at Kostenki about 550 kilometers (350 miles) south of Moscow.

Georgia on my mind.

I’m hoping you still recall that a furor arose over the 1929 discovery by Chinese anthropologist P√©i W√©nzhŇćng of a relatively complete skullcap of a 400,000 year old hominin eventually determined to belong to H. erectus and who the literature calls Peking Man. It engendered a sort of “paleoanthropological origins of humankind” skirmish between Africa and Asia that Africa ultimately won.

Fast forward to 1991 when excavations in Dmanisi made a fossil discovery of the earliest hominid dispersal beyond Africa. Paleoanthropologists discovered several individuals, stone artifacts, and a significant number of well-preserved remains of fossil animals.

[Chart from sites.northwestern.edu.]

Using a technique called paleomagnetism, scientists determined the age of the site as between 1,850,000 and 1,780,000 years. If you think of Earth’s magnetic field as akin to a bar magnet, you can picture the different polarities that allow a magnetic compass needle to point at either the north or south magnetic pole. Periodically, throughout Earth’s history the geomagnetic field reverses symmetrically.

This means the compass that once pointed north will now point south and vice versa. When rocks form or reach the surface through processes I’ve previously discussed, magnetic materials in those rocks effectively lock-in a record of the direction and intensity of the magnetic field at the time of their formation. Scientists can then apply methods such as Argon/Argon dating to date the rocks.

Despite its relatively small size,

[Photo from AtlasObscura [no longer featured] – Gemma Tarlach.]

the Dmanisi site has yielded more than 10,000 animal bones that have been identified as belonging to more than 50 different species of mammals alone. Likely because its location placed it at a transitional zone between an arid climate to the east and a much more humid one to its west, the area was almost certainly a patchwork of forest and grassland and served as a migratory route for animals summering in the higher elevations of the Caucasus Mountains. It was remarkably diverse.

As for the hominins, all of the Dmanisi specimens have brain cases about half the size of modern humans but this brain size and other features correlates quite closely with those of a similar age that have been unearthed in Africa whence this group of hominins originated.

The evidence unearthed indicates that these ancient hominins produced a variety of tools and exploited animal resources. They were likely both predator – some of the animal bones show signs that the hominins butchered them, slicing off meat with stone tools – and prey – others have clearly identifiable gnaw marks. They also appear to have engaged in caregiving behavior.

[Photo from Atlas Obscura – University of Zurich.]

Look closely at the skull second from the right in the digital simulation of the five crania above. This elderly toothless individual would have been unable to eat on their own leaving a clear indication that these ancient hominins cared for their elderly.

The photo below is of the fifth and most recent discovery and it varies in significant ways from the four that preceded it which themselves had some important variations. With what result for modern paleoanthropology? Why, controversy, of course. The core question is whether these fossils represent two (or possibly more) distinct species or whether the variations reflect age and sex differences within a single taxon.

[From Georgian National Museum via Archaeology.org.]

The skull above reveals a low, massive brain case, and a muzzle-like lower face while other individuals in the area have larger brains and more globe shaped brain cases. One study examined a range of cranial features and concluded that relative variation at Dmanisi is comparable to that in similar African fossils and in the variations seen in modern H. sapiens. It concluded that the Dmanisi hominins represent a single paleospecies of¬†Homo but with a wider pattern of sex dimorphism that isn’t present in living hominids.

If the Dmanisi hominins are indeed a single species, then according to Christoph Zollikofer, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Zurich, the fact that the five skulls (above) differ widely shows that H. erectus individuals were far more diverse in appearance than many scientists previously believed.  He further concludes,

that all Homo fossils that date to roughly 1,800,000 to 1,500,000 years ago likely belonged to a single human species. All African fossils of that time period, he explains, variably attributed to Homo habilis, Homo rudolfensis, and Homo ergaster, should be considered part of the species Homo erectus.

which would be a major recategorization of hominins. He might be right. He might be wrong. (‘Or both at the same time.’ – Werner Heisenberg ? )

A few final words on these ancients.

It seems natural to wonder, “What happened to them?” If we note the similarities between these adventurous 1,800,000 year old hominins and those in Africa where is the evidence that this group continued along a similar evolutionary past? One answer might be that the African hominins group faced such different environmental circumstances from the Dminisi group that the former had to adapt to survive while the latter did not. But if this was the case, it seems there should be more recent fossils and perhaps evidence of their gradual extinction and neither has yet been found.

The website Dmanisi.ge provides a likely solution.

The sediments at Dmanisi overlie the uneroded Mashavera basalt, which is dated by Argon/Argon to 1.85 million years ago. The sedimentary stratigraphy of Dmanisi is divided into two main units¬†A¬†and¬†B, which are each comprised of several sub-layers. Stratum A¬†is the latest Olduvai, after which we have the paleomagnetic reversal 1.78 million years ago and Stratum¬†B¬†‚Äď earliest Matuyama. The lower layer of the stratum¬†B contains a calcareous soil formation with penecontemporaneous precipitation of subsurface groundwater calcretes of 30-40 cm thickness, enveloping buried geologic contacts and higher parts of Mashavera basalt. These calcretes provide a critical geochronological control over the stratigraphy of the site and the preservations of the lowest layers.

Volcanic ashes of the stratum A covered the basalt quickly, and contain stone artifacts. Stratum B ashes were quickly deposited, burying human fossils along with thousands of animal bones and artifacts. The complete sedimentation of the site took less than 10,000 years.

In other words, over a relatively short period of time – perhaps as long as 10,000 years or perhaps as brief as a few centuries – volcanoes buried the site in ash creating both an extinction event and an astonishingly well preserved fossil record.

In the next post I’ll take you on a journey 1,700 kilometers (a bit more than 1,000 miles) to the north from Dmanisi to Kostenki. We’ll also be moving forward in time to a period a mere 40,000 years or so BP.

-

It’s just a shot away – Prizren

March 6, 2026 -

Some things looking better, baby – Getting into Kosovo

March 4, 2026 -

Here, where the sky is falling – Kuk√ęs

March 2, 2026 -

That’s when we fall in line ’cause we got Berat

February 27, 2026 -

Walking on the big stuff – a climb to Tragjas

February 25, 2026