Goodbye, Grand Teton. Hello, Yellowstone

It had been another chilly night and when I left Jackson Monday morning I thought the gray-white clouds obscuring the top third of the mountains was fog from the condensing dew. I’d learn later that no, it wasn’t only dew, it was a combination of dew and thick ash.

On my way out of Jackson I turned into the entrance to the National Museum of Wildlife Art. I’d driven past it a few times and it had intrigued me enough to decide to delay my arrival in Yellowstone so I stopped for a visit.

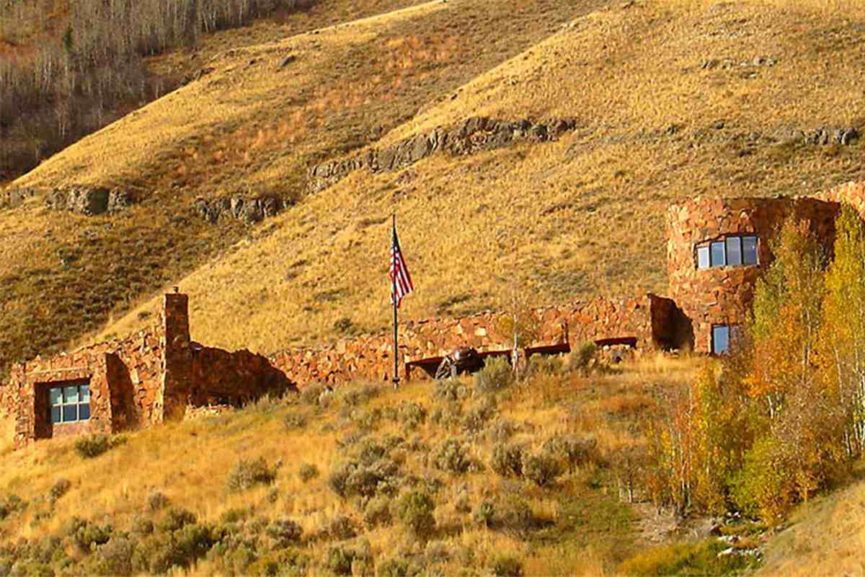

Originally opened on Jackson’s town square in 1987, the museum’s collection quickly expanded and outgrew its space. It moved to its current location in 1994. The 51,000 square foot building is designed to both evoke a Scottish castle and to appear to grow naturally from its surroundings. It’s no accident that the museum’s address is 2820 Rungius Road since Carl Rungius was likely the first artist in America whose art is based solely on wildlife and the Rungius Gallery in the museum’s collection is the largest public display of his works in the United States. Another thread sews Rungius to this trip – his ashes were scattered from Tunnel Mountain in Banff where he had a studio.

As you pull into the drive that leads up the hill, you’re greeted by Bart Walter’s sculpture called Wapiti Trail.

Cresting the hill and entering the parking lot, an expansive sculpture garden greets all visitors. Most of the works are bronze or cast metal, but I found this pair of stylized bison called Buffalo Mountain and Little Buffalo Mountain by Stewart Steinhauer quite interesting.

Once inside, the collection is impressive. It includes works not only by Rungius but by Albert Bierstadt, Rosa Bonheur, George Catlin, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Charles M Russell among many others. I’ll share two other photos in this post and the rest, as usual in a Google Photos folder. The first, is called The Enchantress by Arthur Wardle (My picture of it wasn’t pleasing so I downloaded the image from Wikimedia.) and it enchanted me.

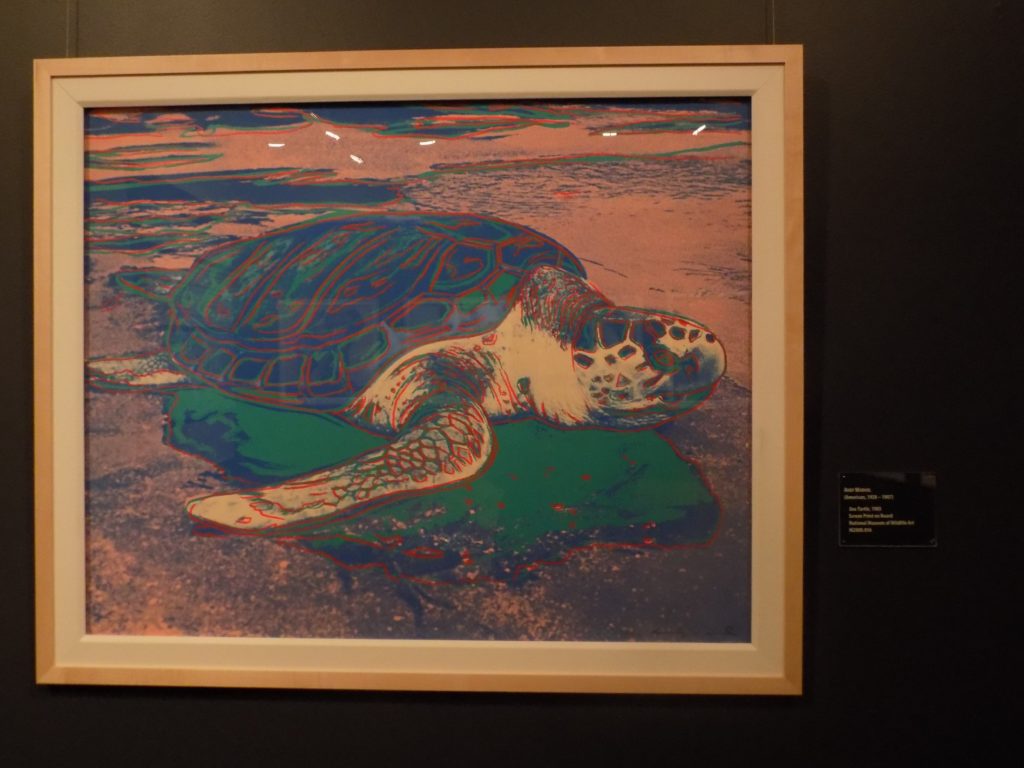

The other is, of course, a turtle.

Yellowstone National Park.

First Stop – Lewis River and Canyon.

U S Route 191 generally closes in late October or early November, however, in the summer months you can comfortably drive along this road from Jackson through Grand Teton NP to Yellowstone NP. Following this route, the distance from Jackson to the West Thumb of Yellowstone Lake is about 80 miles and takes a bit less than two hours. However, the distance between the two parks is something less than half that.

For a 27-mile stretch beginning somewhere in the vicinity of Jackson Lake, route 191 bears the name John D Rockefeller, Jr. Memorial Parkway. Rockefeller played a significant role in enlarging several national parks including Grand Teton. The road bisects the Teton National Forest which is a transitional zone between the giant rocks of the Tetons and the hot springs and lava beds of Yellowstone and creates an unbroken connection between the two parks. What the transitional zone didn’t provide was any relief from the ash in the air. In fact, that aspect of the day seemed to be getting worse.

Although Yellowstone isn’t the largest U S national park, it’s still enormous. (The largest park is Wrangell – Saint Elias National Park in Alaska which is about 3.75 times larger than Yellowstone. Five of its Alaskan brethren and Death Valley National Park in California are also larger than Yellowstone.) At nearly 2,220,000 acres or 3,470 square miles, it’s larger than the states of Rhode Island and Delaware and about 28 percent the size of my home state of Maryland. For those of you who read my journal as I traveled through Arizona and Utah and about the parks I visited on that journey, the combined size of Utah’s Big Five (Canyonlands, Capitol Reef, Zion, Arches, and Bryce) plus the Grand Canyon falls a bit short of matching Yellowstone’s size.

Someone told me that Yellowstone NP is so big and so diverse that it’s like several parks cobbled together. My goal was to experience as much of that diversity as I could crowd into the two days and nights I had planned in the park. This map shows you the approximate route from Jackson and the first four stops I’d make on Monday.

(Note the distance from Jackson to Old Faithful is shown as 101 miles and I wrote above that the distance to the West Thumb is about 80 miles. Yes, it’s true that the distance from West Thumb to the geyser is nearly 20 miles.)

Shortly after passing through the South Entrance to Yellowstone, the road (which now bears three U S Route designations) begins to follow the Lewis River. Named for Meriwether Lewis of the Lewis and Clark Expedition the 18-mile-long tributary of the Snake River flows entirely within the park.

The river starts as a rather unassuming stream flowing about three miles between Shoshone and Lewis Lakes. Once it flows out of Lewis Lake, the river cuts a much more dramatic course through Lewis Canyon

with pockets of whitewater and a small cascade appropriately called Lewis Falls.

Although there’s been significant recovery, the evidence of the 1988 Yellowstone fires which consumed more than 4,000 acres in this area of the park was still easily spotted as I drove along the river and you can see both recovery and lingering damage in this photo and the others.

Allowing the fires to burn naturally has, as the area continues to return to life, created a more diverse habitat of meadows and forests.

Next Stop Isa Lake.

As one might expect, water plays a critical role in the Yellowstone ecosystem. (Air plays a critical role in my ecosystem and by this point, the ash was irritating not just my lungs but my eyes. Uncharacteristically, I’d spend the rest of the day – and much of the rest of the trip – driving with the windows closed and the air conditioning on.) Approximately five percent of the park’s surface area is water most of which can be found in Yellowstone’s 150 named lakes and 278 named rivers and streams that run for a combined length of 2,172.5 miles.

In the map above, Yellowstone Lake is the easiest to spot. At 19 miles long and nearly 140 square miles in area, it’s by far the park’s largest lake. It is, in fact, the largest lake in North America above 7,000 feet in elevation. On the flip side, one of the smallest lakes in the park is Lake Isa. It’s so small that it’s almost impossible to find on park maps. Yet this sliver of a lake is unique in the literal sense of the word not simply in Yellowstone but among every other natural body of water on the planet. Find out why in the next post.

-

It’s just a shot away – Prizren

March 6, 2026 -

Some things looking better, baby – Getting into Kosovo

March 4, 2026 -

Here, where the sky is falling – Kukës

March 2, 2026 -

That’s when we fall in line ’cause we got Berat

February 27, 2026 -

Walking on the big stuff – a climb to Tragjas

February 25, 2026