At various points as you transit around the Yellowstone NP, you’ll see signs like this one:

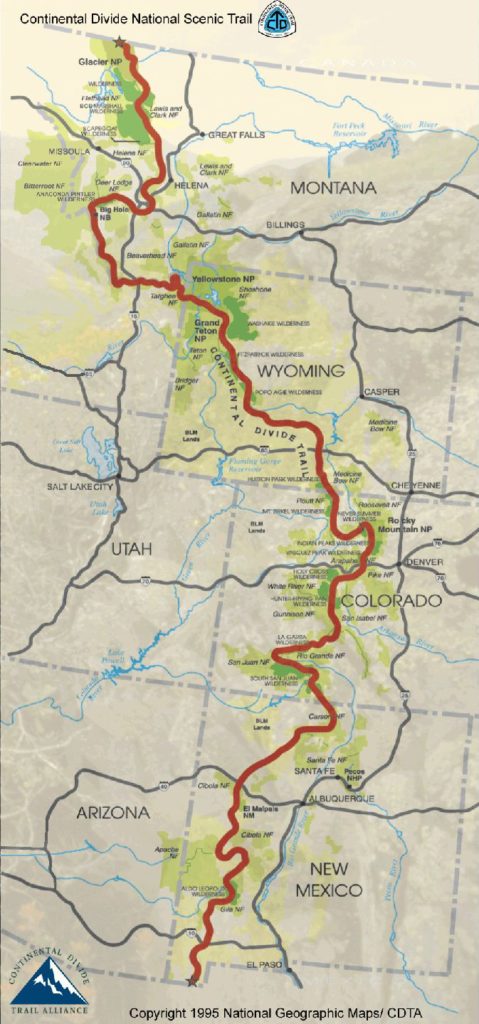

The signs differ principally in reporting the elevation – which ranges from just under 8,000 feet to nearly 8,400. This continental divide is the line that marks the direction of river drainage in North America.

The signs differ principally in reporting the elevation – which ranges from just under 8,000 feet to nearly 8,400. This continental divide is the line that marks the direction of river drainage in North America.

All of the rivers to the east of the divide drain into the Atlantic Ocean while all of the rivers to the west empty into the Pacific. Traveling west from Yellowstone Lake toward Old Faithful along U.S. 191 which, in the park is called the Grand Loop Road, there’s a small pullout on the right to view the sliver of water named Isa Lake. Without presenting any reason, the 1905 book, The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States, states that the lake was “named for Miss Isabel Jelke, of Cincinnati,” but this isn’t what makes it unique.

When you make the short walk to the lake, you see two signs, one with the lake’s name and the other

marking the lake as straddling the continental divide and this is where its uniqueness begins. Isa is acknowledged to be the only natural lake in the world that drains to two oceans. More curiously, it does so backwards. The lake’s western end flows into the Firehole River. The Firehole flows north until it meets the Gibbon River and the two then join to form the Madison River. The Madison flows to Hebgen Lake, joins the Jefferson River and eventually the Missouri River on its way to the Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic Ocean. However, in the spring, Isa’s eastern end runs into Shoshone Lake. That lake drains into the Lewis, Snake, and Columbia Rivers on the way west to the Pacific. (Gatun Lake in the Panama Canal also flows into both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. However, it’s an artificial lake.) While you don’t physically see the divide, the lake’s uniqueness makes it worth the stop to take a photo and make a memory.

marking the lake as straddling the continental divide and this is where its uniqueness begins. Isa is acknowledged to be the only natural lake in the world that drains to two oceans. More curiously, it does so backwards. The lake’s western end flows into the Firehole River. The Firehole flows north until it meets the Gibbon River and the two then join to form the Madison River. The Madison flows to Hebgen Lake, joins the Jefferson River and eventually the Missouri River on its way to the Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic Ocean. However, in the spring, Isa’s eastern end runs into Shoshone Lake. That lake drains into the Lewis, Snake, and Columbia Rivers on the way west to the Pacific. (Gatun Lake in the Panama Canal also flows into both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. However, it’s an artificial lake.) While you don’t physically see the divide, the lake’s uniqueness makes it worth the stop to take a photo and make a memory.

On to the Kepler Cascades

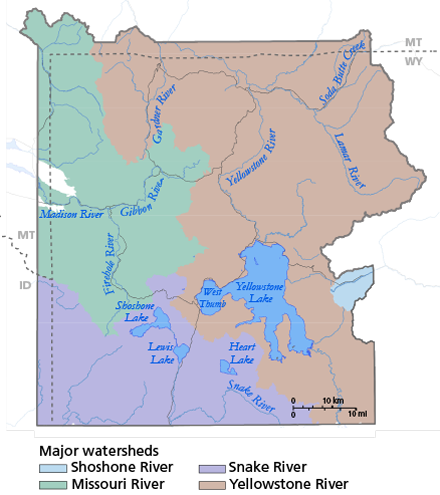

As for the rivers, there are four major watersheds within the park as shown on this National Park Service (NPS) map.

The Kepler Cascades are part of the Firehole River which you can see in the green Missouri River watershed. The NPS website contains this brief description of the Firehole River, “Home to several species of trout, the Firehole River is a favored fly fishing spot. Most of the outflow from the park’s geyser basins empties into the Firehole River causing it to be warmer with larger concentrations of dissolved minerals (chemically richer) than other watersheds.”

The Kepler Cascades are part of the Firehole River which you can see in the green Missouri River watershed. The NPS website contains this brief description of the Firehole River, “Home to several species of trout, the Firehole River is a favored fly fishing spot. Most of the outflow from the park’s geyser basins empties into the Firehole River causing it to be warmer with larger concentrations of dissolved minerals (chemically richer) than other watersheds.”

The Kepler Cascades are about four miles west of Isa Lake and two or three miles east of the Old Faithful Geyser. This series of cascading rapids cuts through the rocky canyon with a total change in elevation of about 150 feet. The longest single drop is about one-third of the total. As much as I would like to think that the falls were named for the great mathematician and astronomer Johannes Kepler, the truth is they were not. Philetus Norris, Yellowstone’s park superintendent named the falls in 1881 for Kepler Hoyt the 12 year old son of John Hoyt then Wyoming’s territorial governor. (Perhaps young Mr. Hoyt was named for the scientist.)

Icelandic gushers!

No visit to Yellowstone is complete until you’ve seen a geyser or ten and just east of the Kepler Cascades pullout you’ll find the trailhead for the Lone Star Geyser. The NPS describes the 2.4 mile walk as a level trail that follows the Firehole River that’s open to cyclists and hikers though cyclists aren’t permitted beyond a barrier close to the geyser. Lone Star Geyser is said to erupt about every three hours spewing water 30 to 45 feet in the air and, unlike the much more famous Old Faithful whose eruptions spurt two and a half to three times as high but last just a few minutes, the eruptions at Lone Star, including the steam phase, typically last nearly half an hour. I thought it might be worth the walk.

Because geysers require a very specific and limited set of physical conditions, they are a relatively rare phenomenon and are often found concentrated in relatively small areas. The nine geyser basins of Yellowstone National Park hold 300 to 500 periodic spouters – roughly half the world’s geysers. (Some hot springs spout water continuously and can be mistakenly labeled geysers. True geysers are periodic and must recharge between eruptions.)

Geysers are usually found in clusters and the second largest concentration, about 200 geysers, is in the Valley of Geysers on the Kamchatka Peninsula in Russia. While some of the world’s most famous geysers can be found in Haukadalur Iceland, the land whose language gave us the English word geyser, this nation is home to far fewer geysers than either Yellowstone or Kamchatka. (The Icelandic word “geysa” meaning “to gush” was adapted to name the original periodically spouting thermal hot spring Geysir {sometimes called The Great Geysir}. Examinations of the opaline silica also known as geyserite or silecious sinter around Geysir indicate that it has been active for about 10,000 years though the specific name Geysir, {pronounced Gay-seer} which became the English geyser, doesn’t appear in written records until the 18th century.)

In the simplest terms, a geyser is a vent in the Earth’s surface that periodically ejects a column of hot water and steam. However, in order to do that, three conditions must be present. The first is heat. Or, more precisely, intense heat. The second is sufficient groundwater under high pressure in an underground reservoir. And finally, fissures, fractures, and other porous spaces to deliver the water to the surface.

One of the few sources near the Earth’s surface capable of producing sufficient energy to heat the pressurized water are the heated rocks or magma associated with volcanoes. (Yellowstone is actually a super volcano waiting to erupt – but I’ll have more on that in a later discussion about the park.) When water is heated, it turns to steam which occupies 1600 times more space as the original volume of water. Thus, when superheated groundwater, confined at depth, becomes hot enough to blast its way to the surface, a geyser erupts.

There’s a wonderful description from geology.com:

Cool groundwater near the surface percolates down into the earth. As it approaches a heat source below, such as a hot magma chamber, it is steadily heated towards its boiling point. However, at the boiling point the water does not convert into steam. This is because it is deep below the ground, and the weight of cooler water above produces a high confining pressure. This condition is known as “superheated” – the water is hot enough to become steam – it wants to become steam – but it is unable to expand because of the high confining pressure.

At some point the deep water becomes hot enough, or the confining pressure is reduced, and the frustrated water explodes into steam in an enormous expansion of volume. This “steam explosion” blasts the confining water out of the vent as a geyser.

There are actually two types of geysers. Grand Geyser in Yellowstone, which is the tallest predictable erupting geyser is an example of a fountain geyser. These erupt from pools of water in intense, sometimes violent, bursts. Although I didn’t visit it, this photo from Wikimedia shows a Grand Geyser eruption.

Lone Star and Old Faithful are both cone geysers. These geysers erupt from cones or mounds of sinter in a steady jet of steam and water that can last for as little as a few seconds or as long as half an hour such as I hoped to see when I completed the hike to Lone Star. The eruptions last until all the water in the reservoir has been ejected and will recur once the reservoir has refilled.

You’ll have to read the next post to learn what happened on my way to and when I reached Lone Star Geyser.