Finding the center that’s not then losing my way – part 2 – Wild Bill

Yes, there really was dead wood.

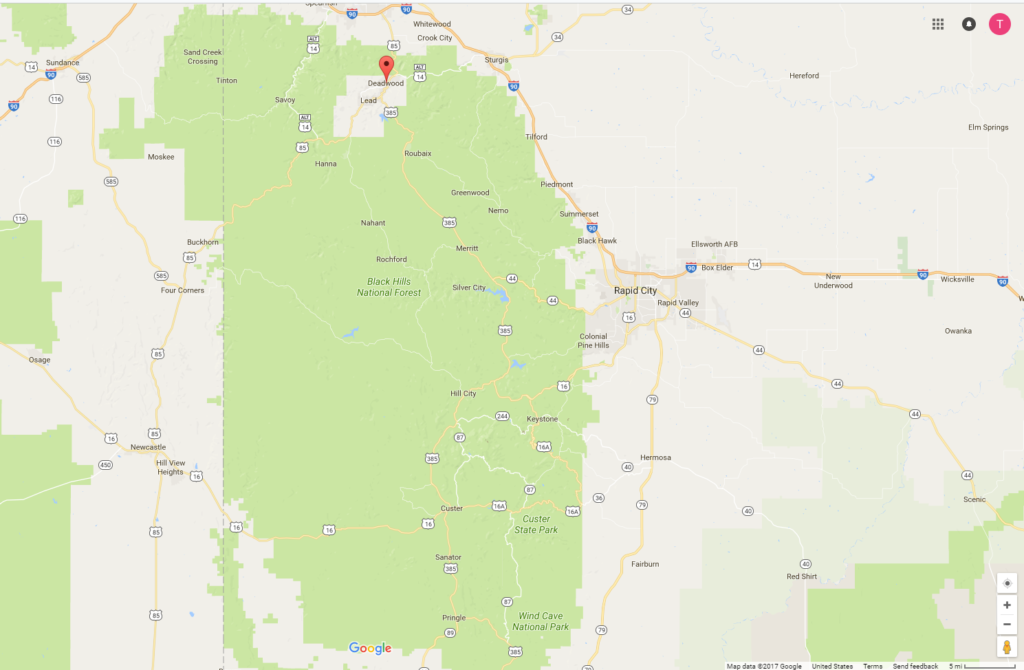

There were no settlements at the present site of the city of Deadwood, South Dakota until 1875 or 1876. I hope that when you take a look at the map below, the reason will be immediately apparent.

(In case it’s not, here’s a TL;DR summary: That large green area around Deadwood is the Black Hills National Forest. The 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie granted the Black Hills to the Sioux in perpetuity. George A Custer led an expedition to the Black Hills in 1874. His reports of finding gold were likely exaggerated by General Alfred Terry in his dispatch sent east. A gold rush ensued.)

In 1875, a miner named John Pearson found gold in a canyon he named Deadwood Gulch because the canyon’s walls were lined with dead trees. Starting as a mining camp, the settlement grew rapidly. By 1876, the population had jumped from zero two years prior to a number exceeding 5,000. This means it housed about four times the city’s current population. Buildings began to replace the mining camp’s tents and, beginning to see itself as a town, it dropped the ‘gulch’ but retained the name Deadwood.

Early on, most of these wooden buildings were either saloons, dance halls, brothels, or gambling establishments – all seen as legitimate businesses and eagerly patronized by the miners. As one might expect from a town filled with such enterprises, Deadwood also attracted an abundance of criminal types and its reputation for lawlessness was well deserved.

While my visit to Deadwood included a lunch stop on Main Street and a visit to the small but jam packed Adams Museum, perhaps the pivotal spot for me was my visit to Mount Moriah Cemetery. This smalltown cemetery holds the remains of more than one of the American west’s most famous legends. Though for some it’s simply because Mount Moriah is their burial site, all are, in some way, attached to Deadwood beginning with

James Butler Hickok.

The man who would become known as “Wild Bill” Hickok was born on 27 May 1837 in Troy Grove, Illinois. In 1861, Hickok joined the Union Army and, although he was nominally a teamster, it was his exploits as a sharpshooter and spy that earned him the nickname “Wild Bill.” After being acquitted of a manslaughter charge in 1865, Hickok was appointed as a Deputy United States Marshal in Fort Riley, Kansas in 1866. Staying in Kansas, he would nonetheless move on over the next five years to become marshal first in Hays and then Abilene. Hickok was an unconventional lawman and generally, wherever he went, controversy about his terms as marshal followed.

A particular talent of Hickok’s was his purported ability to handle his guns equally well with either hand. Perhaps as a form of intimidation, he carried them in his belt in an unusual “butts forward” style that some others would eventually imitate.

[The public domain photo of Wild Bill Hickock above is from Wikipedia and their caption says that the knife is likely a photographer’s prop.]

Hickok was known as one of the west’s fast guns and he had no hesitation using them. He is documented to have killed at least six men though he claimed to have killed many more.

Though only 39 years old, Hickok was in poor health when he married Agnes Thatcher, 11 years his senior, in March 1876. Hickok left Thatcher in June when he joined Charlie Utter’s wagon train – carrying a “needed commodity” of 180 or so prostitutes to Deadwood.

Not long after he arrived in Deadwood, Hickok was murdered there on 29 August 1876 by Jack McCall with whom he’d had a dispute over a poker game the previous night. Two legends arose from his murder. The first was that Hickok, who always sat with his back to the wall was unable to take his customary seat and that Charlie Rich (neither the country singer nor even an ancestor as far as I can tell) twice refused Wild Bill’s request to change seats. The second is that Hickok was holding two pair – black aces and black eights – and the nine of diamonds. True or not, this combination now bears the moniker “The Dead Man’s Hand.”

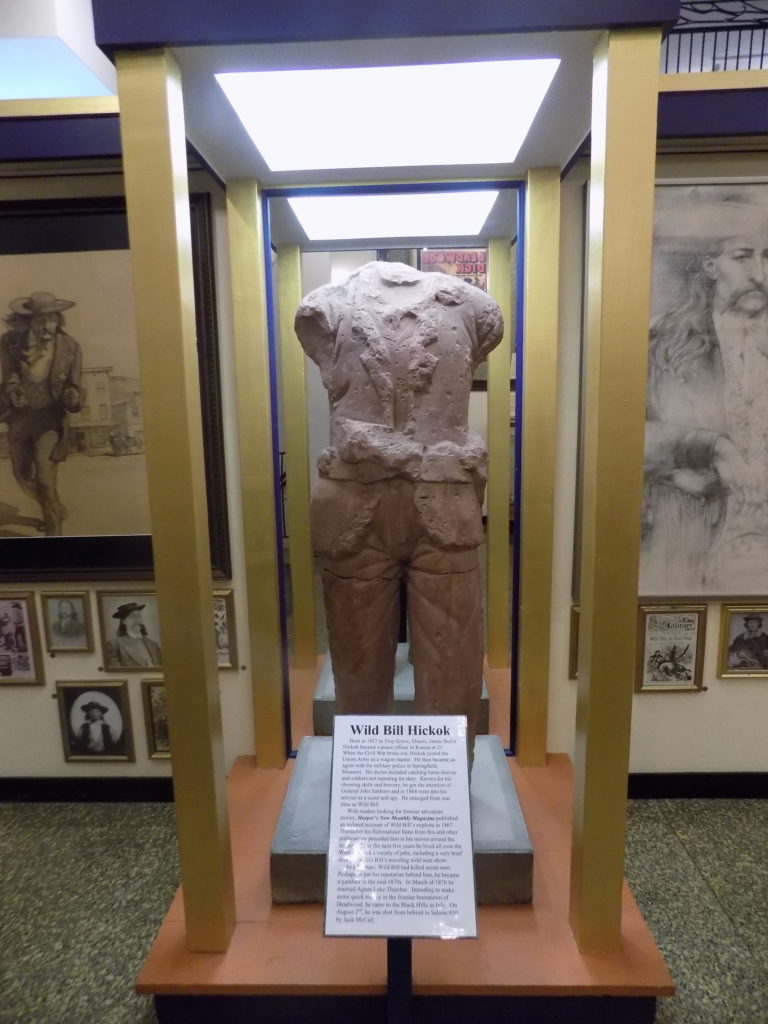

There’s a small exhibit about Hickok in The Adams Museum where I went after lunch

and he’s one of the many “celebrities” buried in Mount Moriah Cemetery.

As for McCall (who’s not buried in Deadwood), he may have been one of the few Americans tried twice for the same crime. Most Americans are immediately familiar with the proscription against self-incrimination in the U S Constitution’s Fifth Amendment. The amendment also protects against double jeopardy. The text reads:.

No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a grand jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the militia, when in actual service in time of war or public danger; nor shall any person be subject for the same offense to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.

After killing Hickok, McCall failed in his escape attempt and was quickly apprehended when he was found hiding in the back of a local butcher shop. Facing a jury of local miners and businessmen, he was tried the next day in McDaniel’s Theater. In his defense, McCall said he was avenging his brother who he claimed Hickok had killed in Abilene. The jury returned a verdict of not guilty in less than two hours.

Uncertain of his safety if he stayed, McCall left Deadwood and resettled in the Wyoming Territory. There he frequently boasted about killing Hickok in a fair gunfight. Officials in Wyoming were having none of it. They arrested him and tried him again for Hickok’s murder on the grounds that the initial trial had been held on the Sioux Reservation and not in the United States and thus, its verdict and findings were not valid.

A Federal Court in Yankton in the Dakota Territory agreed that double jeopardy didn’t apply. McCall was tried for Hickok’s murder a second time. He was convicted and hanged in March 1877.

-

It’s just a shot away – Prizren

March 6, 2026 -

Some things looking better, baby – Getting into Kosovo

March 4, 2026 -

Here, where the sky is falling – Kukës

March 2, 2026 -

That’s when we fall in line ’cause we got Berat

February 27, 2026 -

Walking on the big stuff – a climb to Tragjas

February 25, 2026