In recounting my previous extended stay in Lisboa, a substantial section of one post was essentially a paean to Organic Maps. It works offline without tracking the user and it was almost universally more efficient than the more common alternative – Google Maps. For some reason, it didn’t work as well on this trip and, when I needed such help, I switched back to the latter albeit reluctantly.

Oftentimes when I set out to wander the city I have no aversion to getting lost. In fact, sometimes that leads to an interesting discovery. Other times it leads to my exclaiming, “Oh, I know where I am!” However, as I told my visitors, I’d explored the city enough to frequently know how to get from point A to point B or point A to point C but I might not always know my way from B to C. Those could be among the times that necessitate the use of a navigation aid. I’d also use a map to plot a course when going someplace I’ve never been. This was the case Friday morning when I set out to walk to Lisbon’s largest public cemetery – Cemitério do Alto de São João.

Google Maps suggested two routes from my starting point. The first had 14 steps (discounting the first six which are essentially nonsense) and traveled 2.6 kilometers with an ascent of 82 meters. The alternative required only nine steps (again discounting the first six) ascended only 68 meters but was 300 meters longer. It doesn’t even suggest the easiest (least hilly) and most direct alternative – that I discovered on my own on my return – one requiring only three steps and ascending 65 meters but one that’s half a kilometer longer than the shortest route. (Both of Google’s suggested routes had descents that equalized the net elevation change.) Shouldn’t Google at least give me the option of choosing the easiest route? Of course, had I focused on the map rather than the proposed routes, I would have spotted this myself so I’ll accept some responsibility.

A serene necropolis

Once again I assume regular readers are unsurprised to find me writing about visiting a cemetery. I provided much of the wherefore when I visited the Cemitério de Prazeres Lisbon’s other large municipal cemetery. One of those reasons is that cemeteries are often places of serenity. (I didn’t find that peace in Prazeres because it’s directly in the flight path to Aeroporto Humberto Delgado and and only about eight kilometers distant so all moments of budding tranquility were promptly disrupted by low flying aircraft.) In that respect, Cemitério do Alto de São João, with its long avenues of crypts and views of the Tejo was quite different from its crosstown neighbor.

Père Lachaise em Lisboa?

I write this section header with tongue slightly in cheek. If you enlarge the first photo in this post, you’ll see that the sign says CEMITERIO PUBLICO DO LADO ORIENTAL DA CIDADE DE LISBOA. This is unrelated to the fact that the cemetery, which opened in 1833 during a cholera outbreak was initially used mainly by people of Asian heritage. The more prosaic translation of the above phrase is PUBLIC CEMETERY ON THE EAST SIDE OF THE CITY OF LISBON. You may recall that when the famous Parisian cemetery first opened it wasn’t named for Père Lachaise but rather was called Cimetière de l’Est or Cemetery of the East. (I do need to acknowledge that some historical sources do say that the Lisboa cemetery was, in fact, called the Oriental Cemetery for some time.) A more precise guide would place Alto de Sao Joao to the east of (and higher than) Barrio Alto in the mainly working-class Penha de França quarter. It’s between Santa Cruz to the west and Madre Deus to its east.

As I have found to be the case with many cemeteries around the world, one can infer (correctly or not) aspects of a nation’s history from the graves. I’m generally not someone who takes photos of the graves that look unattended or in decline such as can be seen in this photo from the website Stone and Dust.com

because it feels a bit too intrusive to me – as if I might be somehow shaming the surviving family members. But there are scores of similar gravesites in this cemetery that are perhaps a reflection of the neighborhood itself and of the depths of recent poverty of what has long been one of Europe’s poorest countries. (Of course there may be other reasons, too. The last person entombed could have been the last of that familial lineage, for example. Or the family might no longer reside in Lisboa or even in Portugal. And so on.)

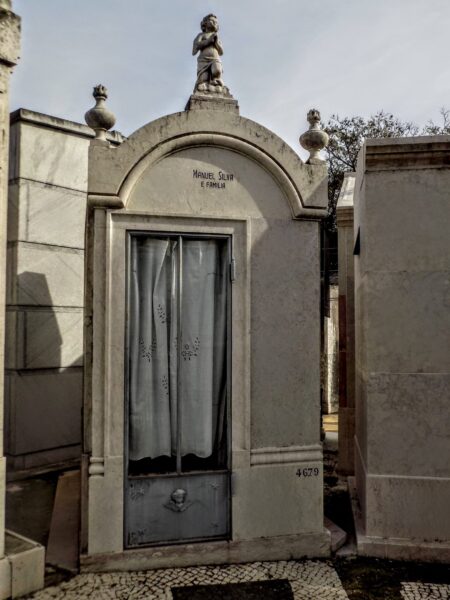

On the other hand, I was intrigued by a number of well-maintained crypts I spotted that, like this one,

provided a measure of privacy for its occupants. I couldn’t help but wonder why or what those corpses might be doing behind their curtains.

Memorials

On my first visit to Lisboa in 2022, one of the first stops I made with Ana was at this memorial on the Avenida da Liberdade

honoring the lives of the more than 11,000 Portuguese soldiers who died in the First World War. At the outset of that “war to end all wars”, Portugal sought to remain neutral – as it would do with greater success in World War Two. However, when Germans began attacking outposts in what was then Portuguese East Africa (now Mozambique) the United Kingdom invoked the 1386 Aliança Luso-Inglesa or Anglo-Portuguese Alliance. Portuguese soldiers then fought beside Allied forces on the Western Front. The monument commemorates the lives of the 55,000 Portuguese troops who fought in that war and the more than one in five who died. There’s an additional memorial in Alto de São João commemorating, as nearly as I could determine, the lives of the unknown soldiers.

Not entirely calm, serene, completely carefree

Alto de São João is a working cemetery so, when I arrived not only was a funeral in progress but the crematorium was operating. Although you might have to enlarge the first photo above and still look very closely to see the smoke, the smell was unmistakable. Fortunately, it dissipated quickly.

The crematorium,

which opened in 1925, was the first such facility in Portugal. It initially operated for only 11 years before it was shut down by the Estado Novo government. (I could find no official reason but it might have in some way been related to the Catholic Church prohibition of cremation until 1963.) It reopened in 1985 and has been operating since then.

The other break in my moments of serenity came from the very vocal mourning of an individual whose cries echoed through one of the cemetery’s “neighborhoods”. I could sense how deeply this person felt their unrecoverable loss.

I have very little to report of the next few days. Saturday, Monday, and Tuesday were particularly mundane and, other than being in Lisboa and walking through different neighborhoods little different from what I would do at home in the States. Sunday I rode the train to Cascais and spent some time with Ana and MC. You can see all my photos from Cemitério do Alto de São João here and the few from those other days at this link.