When I First Saw You

On my walk near the river the previous Thursday I passed a building I’d previously seen and made mental notes to visit because I was intrigued by its exterior,

its name, and its contents. I found the name interesting because of the signs in the window. In Portuguese this is the Berardo Museu Art Deco. The signs shorten it to B-MAD. Now, while art deco has never made me mad, it is a style I’ve long found attractive.

Situated in Lisbon’s Alcântara neighborhood, the B-MAD is located in the restored the former summer residence of the Marquis of Abrantes which he initially built in the first half of the eighteenth century. In the first decade of the 20th century Guilhermina Júlia da Cunha Pereira Flores acquired the building. Her son, physician and researcher António José Pereira Flores, hired his friend Raúl Lino – a noted architect – to enlarge the building in the 1920s to accommodate his growing family. Lino added the second and third floors as well as a turret with a belvedere and an imposing staircase.

The walk from my flat was about 4.5 kilometers and when I reached there I could sense the beginning of my improving Portuguese because after I greeted the woman at the desk and told her I wanted a single ticket, she asked me in Portuguese if I wanted my guided tour in Portuguese or in English. (You can only go through this collection with a guide.) I chose English. My Portuguese had improved but not that much.

The collection actually begins in the period of art nouveau.

(The Art Nouveau movement began in Europe in the 1890s led by the Belgians Victor Horta and Henry Van de Velde. It sprung from an impetus to create a new style for the coming new century that embraced and emphasized craftmanship against the backdrop of the industrial revolution. Its inspirations emanated from natural imagery but emphasized geometric shapes – particularly arcs, parabolas, and semicircles. In Art Nouveau shape was more important than color and the style generally used muted shades such as burnt orange, olive green, soft blues, and mustard yellow.

Although Art Nouveau influenced design disciplines from architecture to furniture to interior and graphic design as well as fine art and sculpture, its emphasis on hand-made craftsmanship made it an expensive one to support. As a result, it never became particularly popular with the general public and by 1910 the relatively short-lived movement essentially came to its end because the industrial sponsors, educated bourgeoisie class, and other elites who patronized it lost interest in it.)

Although more than a decade and the First World War intervened between the end of Art Nouveau and the rise of Art Deco, it wouldn’t be entirely out of place to point to the former as inspiration for the latter even if there were significant differences between them.

Unlike Art Nouveau and its focus on curved lines and muted colors, Art Deco used bold often contrasting colors and emphasized straight lines as you can see in the cabinet in the photo above or the painting below.

Another crucial difference between the two is the latter’s embrace of modern manufacturing techniques and its use of materials like chrome, stainless steel, and inlaid wood whereas the former stressed hand-made work and the use of natural wood and cloth.

(Curiously, although the movement took its name from the 1925 Exposition Internationales des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris, the first known print appearance of the term didn’t occur until 1966 in the title of the first modern exhibit on the subject, called Les Années 25 : Art déco, Bauhaus, Stijl, Esprit nouveau.)

At the end of my tour, I was offered the opportunity to visit the garden terrace and sample some Bacalhôa Vinhos de Portugal – a century old winery that was also among Joe Berardo’s holdings. I declined mainly because my wine palate is far from sophisticated and those subtleties would be lost on me.

This is Nice, Isn’t It?

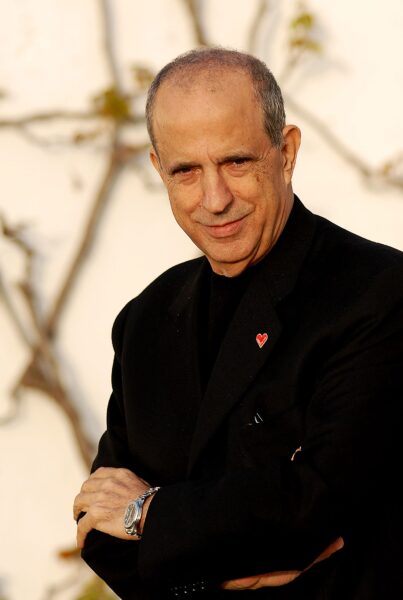

Visiting museums can transform a person in many way both expected and unexpected and, while I savored the chance to let my eyes drink in many of the items displayed at B-MAD, the way I perceived my experience their shifted considerably when I began to look into the background of the museum’s patron and founder José Manuel Rodrigues Berardo (AKA Joe Berardo).

Initially I was impressed by his apparent generosity. The B-MAD is not the only reflection of Berardo’s collection. Even the list that appears here doesn’t reflect all of ways in which he’s opened his private collection to the public.

You might recall that K, P and I had a wonderful visit to the Calouste Gulbenkian Mueum and that I’d dipped a toe into the biography of that museum’s collector and benefactor. While my overview of Gulbenkian’s life and the manner in which he accumulated his wealth led me to conclude that he’d carried an attitude of colonial European superiority and arrogance, he acquired his wealth though mainly legitimate means. However, reading the hagiography that appears on the Berardo collection’s website raised some suspicions. And talking with Ana confirmed the need to more carefully examine his background.

Berardo was born on the Island of Madeira in 1944 but he emigrated to South Africa in 1962. Initially working in the field of horticultural distribution, Berardo was involved in establishing Egoli Consolidated Mines, Ltd. in 1968 which is when he began to amass his considerable fortune before returning to Portugal in 1986. An activist stock investor, by the early 2000s, Berardo had an estimated net worth of nearly € 2 billion.

(From Wikipedia by Pedro Vilela)

However, his behavior roused some suspicions along the way. As early as 1990 he was called in front of a Commission of Inquiry for allegedly illegally exporting cycads from the Transvaal to Madeira, and for declaring the value of the plants to be less than one tenth their purchase price.

There were some other questionable dealings along the way building toward a crescendo when, in 2019, Banco Comercial Português, Novo Banco, and Caixa Geral de Depósitos filed a lawsuit aimed at collecting his debt of 980 million euros against which he had pledged his personal art collection valued at approximately € 316 million as collateral despite the fact that he had signed an agreement in 2006 with the Portuguese government to loan art from his collection on a long-term basis to the Centro Cultural de Belém in Lisboa. This prompted the Assembly of the Republic to open an inquiry into the matter and Berardo testified that none of the loans were personal but were for companies he was associated with.

Berardo was arrested in July 2021 on suspicion of tax fraud and money laundering. The government was also investigating other possible crimes such as forgery of documents and breach of public order. To the best of my knowledge the case hasn’t yet been resolved but learning this certainly left a sour aftertaste in my impression of his collection. I’m glad I didn’t drink his wine.

I didn’t take too many photos of the collection but you can see them here together with some random photos from my Friday walks through Bairro Alto and Alfama.