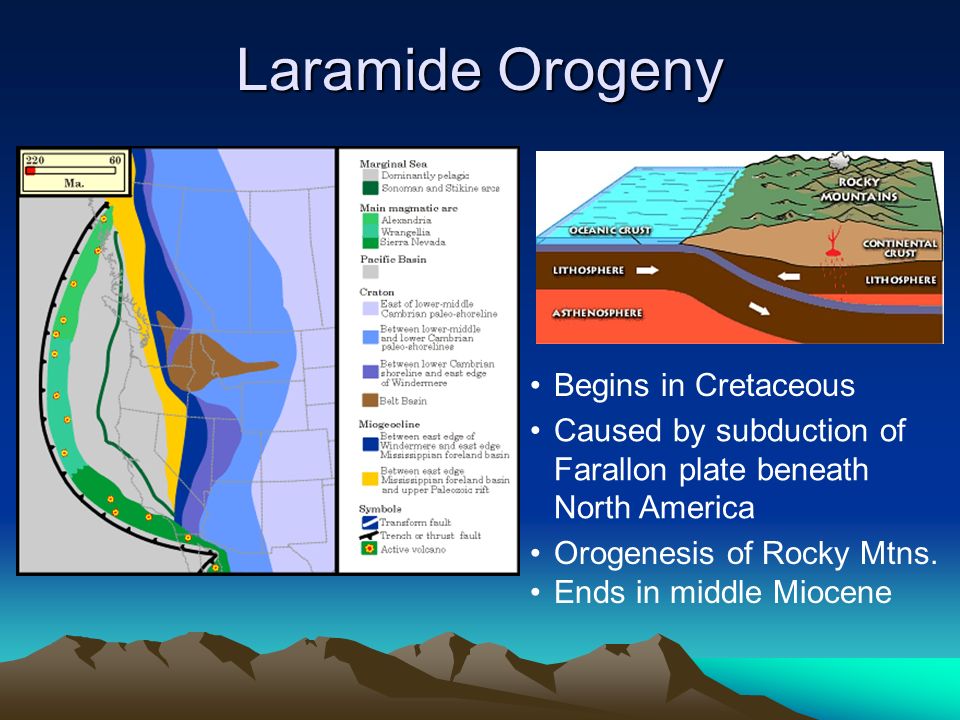

In the previous post I noted that the Rocky Mountains rose up during the Laramide Orogeny.

Thus, you might reasonably expect that the exposed rocks would be mostly from that period. That’s not quite the case and it’s due to a pre-existing land form known as the Laurentian Plateau.

Sometimes called the Canadian Shield, the Laurentian Plateau, is a large area of Precambrian igneous rock that once formed the geologic core of Laurentia – the supercontinent that eventually became North America. A tectonic plate called the Kula plate subducted against the North American plate as part of the process that raised the Rockies. However, as the subduction of the Kula plate pushed toward the east, it met considerable resistance from the Laurentian Plateau and exposed much older rocks. Some of the rocks, particularly those on the east side of Banff, are as old as 600 million years and date from the Precambrian. Others are as young as the lower Cretaceous (145–66 MYA.).

How did this happen? Picture the expanding and collapsing seating area in a gymnasium. The hardwood floor underneath the seats would be the Laurentian Plateau and the seating area would be the ancestral rocks. After a game, the crew pushes against the seats causing them to fold in on each other. In the case of the Canadian Rockies, the crew would be the subduction of the Kula plate smashing into the rocks. As the seats fold in, they rise ever higher. This process ended in the Canadian Rockies about 55 million years ago. The main difference between the seat analogy and the geologic process is that, in the latter, the plateau would also experience some folding while the floor underneath the seats does not.

Rubbing mountains the right way

As the Laramide Orogeny ended, it’s likely that height of the Canadian Rockies was in the range of 8,000 meters – comparable to today’s Himalayas. But once the mountain formation process ceased, erosion was free to move in as the dominant force in shaping the mountains.

Over the past 80 million years, erosion has taken its toll on the landscape, with more extensive erosion occurring in the foothills and Front Range than in the Main Range. Early in the process, water was the principal erosive force.

We’ve seen that Banff’s mountains exhibit several different shapes. These have been influenced by the composition of rock deposits, layers, and their structure. Numerous mountains in Banff are carved out of sedimentary layers that slope at 50–60 degree angles. Such dip slope mountains have one side with a steep face, and the other with a more gradual slope that follows the layering of the rock formations, such as the example of Mount Rundle, near the town of Banff.

The mountain formations in Banff include complex, irregular, anticlinal, synclinal, castellate, dogtooth, and sawback mountains. Castle Mountain exemplifies a castellate shape, with steep slopes and cliffs. The top section of Castle Mountain is composed of a layer of Paleozoic-era shale, sandwiched between two limestone layers. Dogtooth mountains, such as Mount Louis, exhibit sharp, jagged slopes. The Sawback Range, which consists of dipping sedimentary layers, has been eroded by cross gullies. Scree deposits are common toward the bottom of many mountains and cliffs.

More recently, beginning with the Quaternary glaciation two and a half million years ago, glacier ice carved many of the mountains into their present shapes. In fact, glacial landforms dominate Banff’s geomorphology. Those in the know can see all the classic glacial forms including cirques, arêtes, hanging valleys, moraines, and U-shaped valleys. The pre-existing structure left over from mountain-building strongly guided glacial erosion and this combination accounts for the many varied mountain types seen in Banff National Park today.

Glaciers are the largest moving objects on earth. They’re massive rivers of ice that form in areas where more snow falls each winter than melts each summer. Their scale can be truly gargantuan — the glaciers that form the ice cap covering Greenland hold enough ice to submerge the whole of planet Earth under 17 feet of water. The glaciers of Antarctica are so heavy they actually change the shape of the planet.

As glaciers advance and retreat, they can grind down mountains, scatter strange rock formations across the countryside and reduce solid rock to fine dust. In this process they can leave behind debris of rock and ice called terminal moraine. When this debris dams a river, it creates a lake behind it. Lake Louise in Banff NP is this type of glacial lake.

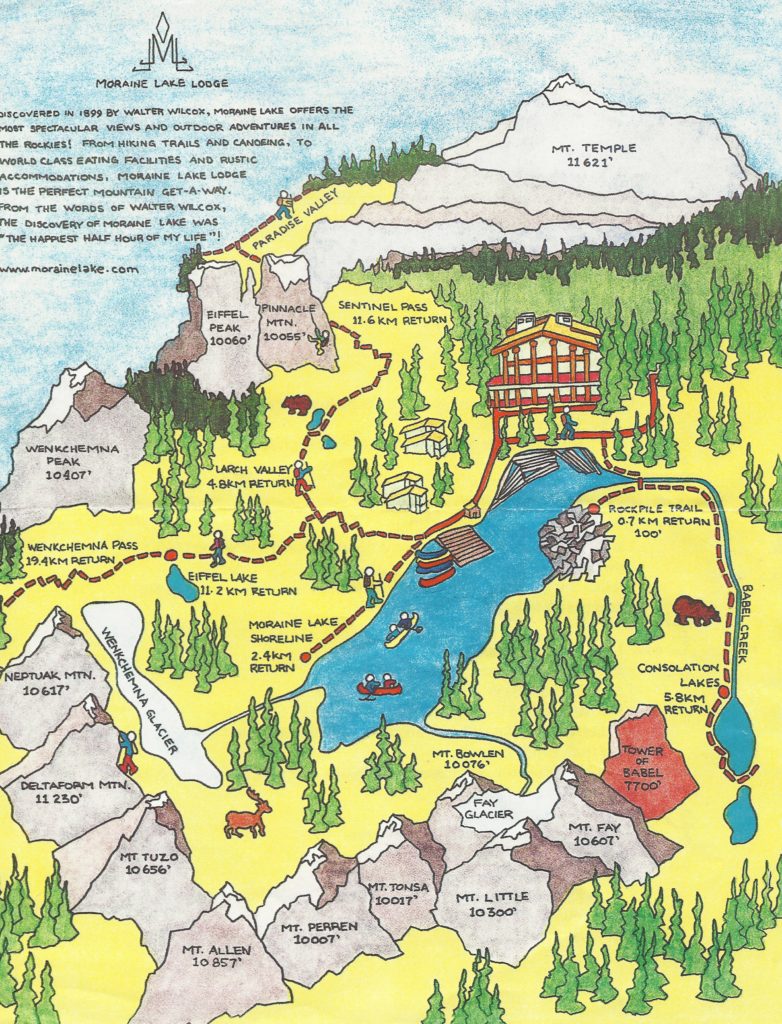

Somewhat ironically, while it is also a glacial lake, Moraine Lake, despite its name, was created differently. It wasn’t formed by damming of melt water by terminal moraine as is the case of Lake Louise; instead, this lake was formed by damming of water run-off from the surrounding mountains by falling rocks. Moraine Lake, where I’ll spend the night, is in the Valley of the Ten Peaks.

At the time the lake crests, generally in June, the intense blue for which it and many of the lakes in Banff NP are famous generally peaks as well. When I was there in August, it looked like this:

The sharp eyed among you might recognize this lake (and the less sharp eyed simply need to look to the right).

The photo was taken from the Rock Pile and my hotel is to the right a bit outside the frame as you can see on the map below.

As glaciers erode bedrock, they can deposit silt size rock particles known as rock flour. When these sediments enter a river, they turn the river’s color grey, light brown, iridescent blue-green, or milky white. When the river flows into a glacial lake such as Moraine Lake and Lake Louise in Banff NP, rock flour creates shades of turquoise. As the increase in water flow from the glacier during snow melts and heavy rain periods increases the extent of the river’s flow, distinct layers of a different colors flow into the lake eventually dissipating and settling to give the lake its distinctive hue.

While there’s more to see and learn, my next entries – including a visit to the towns of Banff (inside the park) where I stopped on Sunday and Canmore (just outside the park) where I had lunch on Monday and visits to Johnston Canyon and Cave and Basin – are more personal and much less technical.

Some final notes

Because of my upcoming trip to Spain and some extended preparations for a trip to France in April 2018, I won’t adhere to a regular publication schedule. So, those of you on my email list can check there, those who follow me on Twitter can watch that site, or simply check the main page from time to time.

And, for those who are curious about the the title for this entry, it was inspired (with no particular relationship to the contents) by this song: