Before Montreal, before the French, before Haudenosaunee (Montreal and me supplement one)

In the time before humans.

Our planet is a dynamic and turbulent place. Tectonic plates slide along faults and crash into one another creating and moving continents and lifting up mountains. In another mountain building exercise, magma boils up from the molten core through subduction zones and gradually accretes on the surface.

The climate changes. Glaciers grow and retreat carving out spaces for lakes and rivers. Rivers can carve canyons and erode those very mountains built by tectonic movement and volcanism. In our all too brief lives, we can feel the impact but never witness the ultimate effect. The geology of the northeastern section of the American continent exemplifies these alternating epochs of creation and destruction in fascinating ways. In this chapter, I’m going to take a look at a tiny sliver of the geologic forces that shaped the area we now call the Province of Quebec and more specifically, the city we call Montreal.

How far can the WABAC machine take us.

Given that mount is part of the city’s name, I could start with the process of orogeny or mountain building. (Those of you who have read my previous posts are, I hope, at least somewhat familiar with the term. If you need a refresher, try this post and scroll down to the section headed ROCKY MOUNTAINS. The uber inquisitive among you might want to read about the Grenville Orogeny because Grenvillian rocks stretch from this part of Canada through Atlanta – a city I’ll discuss in an upcoming entry.) However, I’m going to narrow my discussion to a look only at the large intrusive stock hill immediately west of downtown Montreal. (A stock is an igneous intrusion with less than 100 kilometers of surface exposure.)

For those too young to understand the reference in this section header and for those old enough to experience a touch of nostalgia,

I present above the image of Mister Peabody and Sherman. The narrow scope of my discussion means we won’t be testing the temporal limits of the WABAC Machine although we will use it often. To an educated eye, the view from the top of the hill can take one back a billion or so years into the past. Fortunately, we needn’t look back that far to see the birth of Mount Royal.

At this link there’s a look at Mount Royal courtesy of Google Earth. Given the overall shape of the mountain and the small lake near its peak, there was a time when people thought Mount Royal was an ancient extinct volcano. This is not the case. Mount Royal is one of a series of plutons known as the Monteregian Hills that stretch from Saint-Andr├®-d’Argenteuil in the west to Mount M├®gantic in the east.

(A pluton is a deep-seated intrusion of igneous rock that began as magma several kilometers underground in the EarthŌĆÖs crust that made its way into pre-existing rocks and then solidified. Those who have vicariously journeyed with me might recall encountering the plutons that dot the harbor of Rio de Janeiro.)

One can find hilltop lakes on several of these hills such as Beaver Lake (Lac des Castors) on Mount Royal and Lake Hertel atop Mount Saint-Hillaire some 40 kilometers to the east of Montreal.

[Image from Flickr – Abdallahh.]

While it looks very much like a crater lake, Lake Hertel, like its counterpart atop Mount Royal, was a glacially generated depression as advancing and retreating glaciers combined with other naturally erosive forces to create it.

Now, about those glaciers.

Let’s return to the WABAC Machine and take a great leap forward to a time a mere twelve or thirteen thousand years ago. Kept afloat by our pontoons and aided by our WABAC drone, we see that much of the land that now comprises the provinces of Quebec and Ontario (as well as parts of the U S states of New York and Vermont) was the seabed at the bottom of the Champlain Sea.

(When the last great ice age ended, glaciers no longer blocked the inflow of the ocean. The water rushed in and formed the Champlain Sea which existed for about 3,000 years. Almost immediately after forming, the sea began to retreat. You see, while the glacial melting allowed the oceanic influx, another process called isostatic rebound began to raise the land.┬Ā Parts of the northern hemisphere were covered in ice up to three kilometers thick and under all that weight, the land sagged and deformed. With the weight lifted from its metaphorical shoulders, the land began a slow {and still ongoing} process of uplift and reformation.)┬Ā

Whale fossils (beluga, fin, and bowhead) together with marine shells and fossils of oceanic fish such as capelin found in the areas around Montreal and Ottawa provide a piece of evidence showing the extent of the Champlain Sea while clay deposits – particularly of a type known as Leda clay – in a plain along the Ottawa and Saint Lawrence Rivers provide evidence of the sea itself.

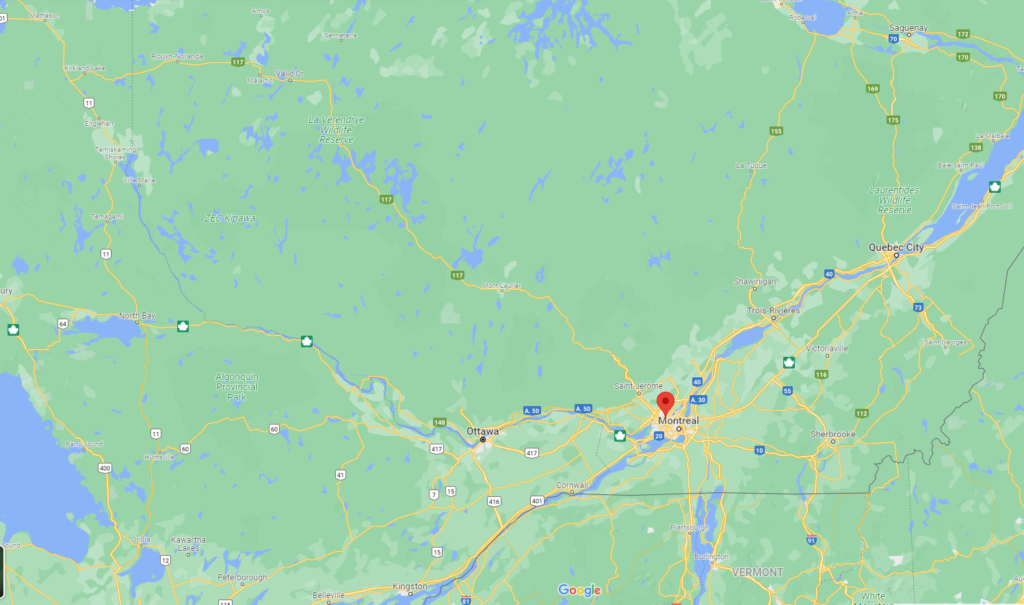

Today, a Google Maps view of the area looks more like this:.

If we were to zoom in on Montreal, we’d see that the city is, in fact, a river island at the confluence of the Saint Lawrence and Ottawa Rivers. It’s the largest island in the Hochelaga Archipelago and the second largest in the Saint Lawrence River.

Now that we’ve taken a brief look at how the land came to be we will next track humanity’s arrival.

-

It’s just a shot away – Prizren

March 6, 2026 -

Some things looking better, baby – Getting into Kosovo

March 4, 2026 -

Here, where the sky is falling – Kuk├½s

March 2, 2026 -

That’s when we fall in line ’cause we got Berat

February 27, 2026 -

Walking on the big stuff – a climb to Tragjas

February 25, 2026

2 responses to “Before Montreal, before the French, before Haudenosaunee (Montreal and me supplement one)”

Yeah checking in Todd, I had to make an appearance here.

I’ll finishing reading this during lunch- but I’ll be back on occasion just say’n.

SH

Thanks for checking in, Shell. I hope you like these. They should be a nice distraction.