A linguistic hint shortens the trip

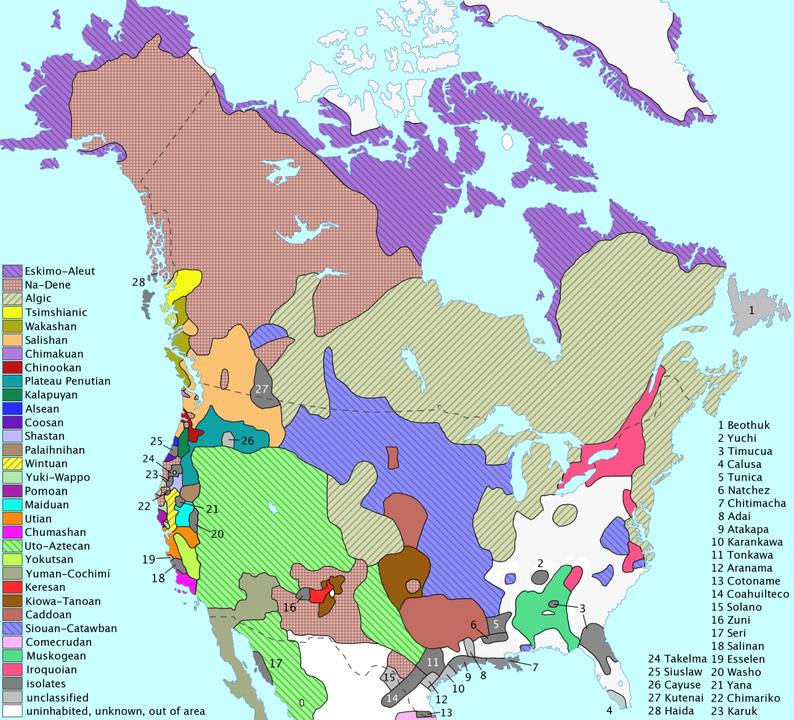

A typical Todd post would likely try to trace the origins of the native tribes living in and around present day Montreal at least as far back as 5,000 years Before Present (BP) to the Paleo-Eskimos who largely displaced an older population that had first crossed the land bridge known as Beringia. The older group was among the very first humans to migrate from Asia and occupied North American Arctic for at least six millennia prior to being displaced. However, I took one look at a map of Native American languages

quickly realized that this would likely lead me down a research path that would consume days of my time and yield a post that would demand your attention for far longer than is my present intent.

The narrow red band that represents the Iroquoian (hereafter Haudenosaunee) family of languages and surround Lakes Toronto and Erie is itself essentially surrounded by the Algic language family. It seems reasonable to conclude that since the groups comprising this population were linguistically distinct, they were also likely culturally and to some degree genetically distinct. So, while I have little doubt it would make a fascinating detour, it would probably be a scenic trip into a steephead valley so I’ll simply posit that the First Nations who would eventually form the Haudenosaunee Confederacy settled in the Saint Lawrence Valley about 5,000 years BP.

A few words about names and terminology

Unless I am writing about a specific tribe or tribal member, I will, for convenience, use the common English rendering. In general, I will use the term Haudenosaunee (People of the Longhouse) which is a confederacy of these five tribes:

Gayogohono (in English, Cayuga) – People of the Swamp

Kanienkehaka (Mohawk) – People of the Flint

Onandowaga (Seneca) – People of the Mountain

Oneyoteaka (Oneida) – People of the Standing Stone

Onondagega (Onondaga) – People of the Hills

This group might be more familiar to many as the Iroquois League.

The Legend of Haudenosaunee

As is the case with most early pre-colonial history in the Americas, written records about the foundation of Haudenosaunee simply don’t exist. There is, however, an oral tradition about two men – one named Hiawatha (though not the Hiawatha in Longfellow’s poem) and one called Dekanawida. Hiawatha was from the Onandowaga tribe and Dekanawida, who is called the Great Peacemaker, was born in the Wendat Nation of southern Ontario.

(From AncientPages.com)

Archaeological studies in this part of Canada describe a culture they call the Owasco with the earliest evidence of settlements being established around 900 CE. The Owasco was followed more than a century later by the tribes that would form the Haudenosaunee confederacy. Oral histories indicate a long period of extended warfare between the various tribes. Like the Owasco, the five tribes built their settlements on hilltops usually within a mile or two of a water source be it a stream or a lake. Unlike the Owasco, the Haudenosaunee settlements were heavily fortified. Additional evidence points to some consolidation of the settlements of the latter group beginning in the fourteenth century.

Archaeologists have also found evidence of both a growing homogenization of material artifacts as well as increased economic exchange within the five Haudenosaunee nations that suggests greater ties between the nations. Dating these artifacts, most scholars place the founding of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy sometime in the mid- to late 15th century CE.

(In 1997, researchers Barbara A. Mann and Jerry L. Fields proposed a founding date of 31 August 1142. They arrived at this by consulting the full oral tradition, archaeology, historical record, and even astronomical and actuarial calculations. The astronomical calculation stems from a legend in the Onandowaga tradition that states “a sign in the sky” led them to ratify the Great Peace. Mann and Fields hypothesized that this sign was a solar eclipse. The only such eclipse they found that would have been visible from the site of the treaty’s signing took place in August 1142 CE. If true, it would place the establishment of the confederacy more than four centuries before the consensus.)

The traditional dates, however, mesh well with the legend of Dekanawida and Hiawatha – the latter of whom is likely to have lived in the fifteenth or sixteenth century. The legend tells that Dekanawida had traveled east from his homeland and was living with the Kanienkehaka when he met a grieving Hiawatha and relieved the man’s grief by engaging in what came to be known as a condolence ceremony.

(From Mohawknationnews.com)

Explaining his vision of a Great Peace to Hiawatha, Dekanawida convinced his new ally to set out together to unite the five tribes.

(Interestingly, the legend of Dekanawida includes a virgin birth, his survival of two attempts to drown him by his mother and grandmother, performance of several miracles, and a prophecy to his mother that he would plant a Tree of Great Peace.)

As is the case with most oral history and legend, details such as date and location are sparse and often overlapping with other legends. In the case of the Tree of Great Peace, it is fairly certain that Dekanawida planted the tree in the territory of the Onondagega. Traditionally, the tree is a eastern white pine which is the only such tree that grows with five needles per fascicle or bundle. This is symbolic of the five tribes of the confederacy.

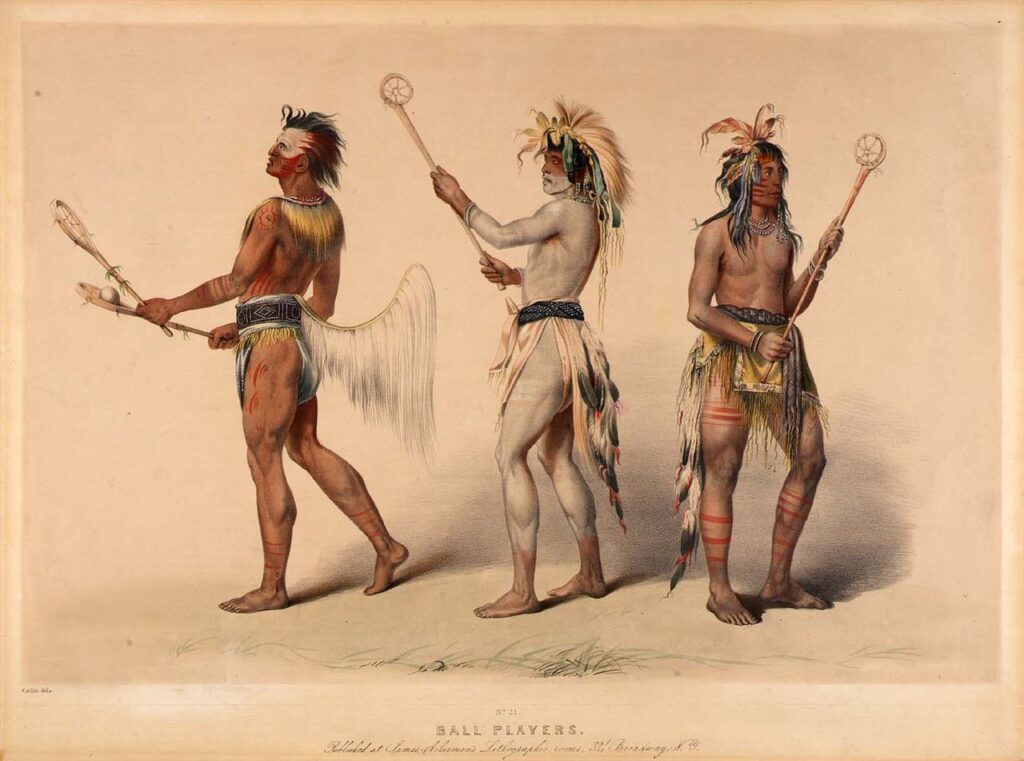

One legend says that Dekanawida had warriors from each of the tribes uproot a pine and throw their weapons into the hole before replanting the tree thus giving rise to the term “bury the hatchet.” Another part of the legend says that the warriors came together to play the Creator’s game called Deyhontsigwa’eh (They bump hips) in the Onondagega tongue or Tewaaraton in the language of the Kanienkehaka. Today, we call that game lacrosse.

(Wikimedia Commons – George Catlin Public Domain)

The Confederacy became one of the most potent political forces in the east and some say it served as an unacknowledged model for some of the ideas underlying the U.S. Constitution.

In the final Montreal chapter, I’ll take a look at the relations between the Haudenosaunee, the French, and the British.

And finally all the Cuyahoga(s) in Ohio make sense! You did a much better job than my 7th grade Ohio history. THANKS!

Am enjoying your recollections/faux travel.

I’ll go with being fortunate enough not to be coping with the distractions of a 7th grader.