We arrived in the port city of Le Havre at 04:30 Sunday (if the scheduled arrival time printed on the day’s activities sheet was accurate) and would remain docked there for two full days. Le Havre is at the mouth of the Seine. Sail any farther and you’d enter the body of water that separates France from England and that we Anglos call the English Channel. Since I’m in France, however, I’ll defer to my hosts and call it, as they do, la Manche or The Sleeve.

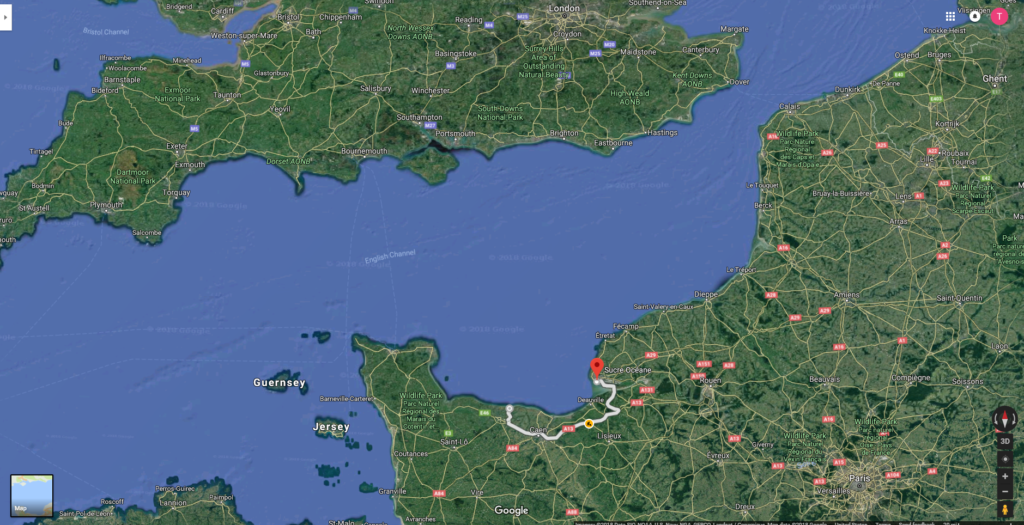

(We were docked in the port area. The city is located on the right bank of the estuary of the Seine barely to the north and east of the red pin that marks the starting point of the route my group would follow to Arromanches which would be our first stop before going in the afternoon to Colleville-sur-Mer the site of Omaha Beach and the American Cemetery. If you enlarge the map, you’ll see Paris in the lower right quadrant. I point this out because you’ll see we haven’t traveled very far – perhaps 180 kilometers or so.)

I should note that if I’m to believe the etymology on Wikipedia,

Until the 18th century, the English Channel had no fixed name either in English or in French. It was never defined as a political border, and the names were more or less descriptive. It was not considered as the property of a nation. Strangely, before the development of the modern nations, British scholars very often referred to it as “Gaulish” (Gallicum in Latin) and French scholars as “British” or “English”.[21] The name “English Channel” has been widely used since the early 18th century, possibly originating from the designation Engelse Kanaal in Dutch sea maps from the 16th century onwards. In modern Dutch, however, it is known as Het Kanaal (with no reference to the word “English”). Later, it has also been known as the “British Channel” or the “British Sea”. It was called Oceanus Britannicus by the 2nd-century geographer Ptolemy. The same name is used on an Italian map of about 1450, which gives the alternative name of canalites Anglie—possibly the first recorded use of the “Channel” designation. The Anglo-Saxon texts often call it Sūð-sǣ (“South Sea”) as opposed to Norð-sǣ (“North Sea” = Bristol Channel). The common word channel was first recorded in Middle English in the 13th century and was borrowed from Old French chanel, variant form of chenel “canal”.

The French name la Manche has been in use since at least the 17th century. The name is usually said to refer to the Channel’s sleeve (French: la manche) shape. Folk etymology has derived it from a Celtic word meaning channel that is also the source of the name for the Minch in Scotland, but this name was never mentioned before the 17th century, and French and British sources of that time are perfectly clear about its etymology. The name in Breton (Mor Breizh) means “Breton Sea”, and its Cornish name (Mor Bretannek) means “British Sea”.

the French shouldn’t be offended if I used the common Anglo term.

Although I chose not to avail myself of the option of eschewing the planned excursions and staying behind one day to explore the city of Le Havre, I’ll tell you a little about it. To begin, here’s a look at Le Havre and its beach courtesy of Wikipedia.

Le Havre, meaning the Harbor, was founded in 1517 by King Francis I and, over time, played a significant part in the slave trade beginning in the 17th century. Other international trade followed and today Le Havre is the second largest port in France in terms of traffic. It’s the country’s largest container port.

For all intents and purposes, the city was totally destroyed during World War II and was rebuilt as a city of concrete over two decades beginning in 1945. UNESCO was so impressed with the work of the Belgian architect Auguste Perret and the working group of architects he supervised that it named Le Havre as a World Heritage Site in 2005. That’s as far as I’m going. If you’re interested in learning more about Le Havre, you’re on your own.

A straight shot to Arromanches.

In military terms (since we’re visiting military sites), if you think of the collective group on our ship as a company (usually 60-200 soldiers) we again, as we did beginning in Paris, split into four platoons (the 40 or so on each of four buses). Two set off for Arromanches-les-Bains (hereafter Arromanches) in the morning and Colleville-sur-Mer (hereafter Colleville) in the afternoon and two flipped the order. Pat and I went on separate tours because after we got on the first bus, Pat returned to the ship to retrieve something she’d forgotten and our bus left before she could get back.

For me, the day turned into an example of a “be careful what you wish for” event so I think Pat might have had the better day of the pair of us. Before we left the ship, William introduced us to the woman who would serve as the guide for our platoon. She was an American living in France whose father had come onto Omaha beach some weeks after the initial assault and she told us that she had some affiliation with the American Battle Monuments Commission that oversees the American Cemetery in Colleville.

With those credentials I suspected she would be the best possible guide. I can’t speak to the competence of the other three guides but from my perspective she was closer to being the worst local guide than the best. On any tour. The first inkling came as we were leaving the port and had to cross the lock connecting the Grand Canal du Havre (on the right in the photo below) with the Bassin René Coty.

As we approached the crossing, she worried aloud that our bus might be delayed when she saw the raised drawbridge (on the right in the above photo) but then made an odd comment about knowing an alternate route. As it turned out, this was simply to cross the bridge on the opposite end of the lock. It seemed clear at the time that this was the intent of the design. When one bridge is raised the other remains lowered so vehicular traffic is never impeded. And I feel quite certain the driver would have known this without her help.

The second came as we approached the Pont du Normandie where there is apparently either some bit of artwork representing the drill bits used in the excavation for the bridge’s construction or the drill bits themselves. She told us to look at them as we passed them but neglected to tell us whether we should look on the left or right side of the bus – a pattern that recurred throughout the day. (“Oh, look at that!” “At what? Where?”)

I should write a little about the Pont du Normandie. With a main span of 856 meters, it’s currently the sixth longest cable-stayed bridge in the world. However, when it opened in 1995, it surpassed the previous record holder by more than 250 meters.

Although the cable-stayed design dates back to the late 16th-century, it’s uncommon – especially in the United States. (The iconic Brooklyn Bridge in New York combines cable-stayed and suspension technologies. The Golden Gate Bridge is a pure suspension bridge.) Because it’s design is rare in the U.S. the bridge had a particularly interesting look to my American eyes.

Unfortunately, the weather that morning was foggy and rainy (and would only worsen throughout the day) so I managed only a blurry photo or two of the bridge through the bus window. Still, I thought it worth a look so I downloaded this picture from Wikipedia. (I deliberately chose a cloudy day.)

Note: In keeping with my 2022-2023 reformation of the blog into shorter entries, backdated to maintain their sequence, any comments on this post might pertain to its new configuration. See the explanation in the post Conventions and Conversions.

Your tour guide sounds like a real “winner”…you would have been better off with me as your guide. At least I would have been honest and told you I have no idea what I’m talking about instead of blowing imaginary smoke….

The history of the the name English Channel was interesting as I have never thought about its origins…until now…

I also liked delving into the names of the beaches. Obviously they had to come from somewhere but again, never really thought about it…..out of the hypotheses given for Omaha and Utah, I lean towards the dogs…

One would think that a french cafe on the coast would have good fish stew…probably why everyone was going to the other place…

Another enjoyable read…can’t wait for the next one…

I was kind of taken with the idea that one of the beaches might have been called ‘Jelly’.