The D-Day beaches

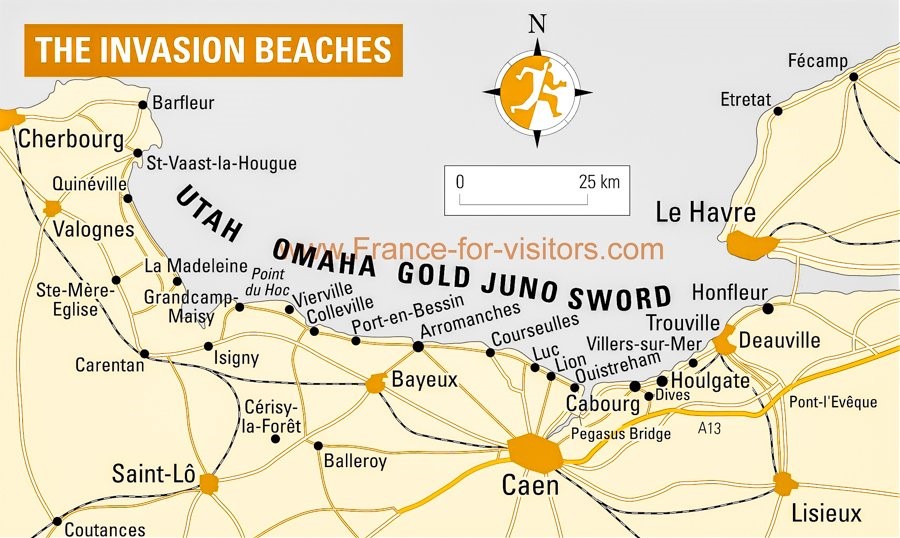

The Allied assault on Normandy that began at about 06:30 on Tuesday, 6 June 1944 spanned a length of coastline that stretched some 80 kilometers from Ouistreham in the east to Saint-Martin-de-Varreville on the west. From east to west, the five beaches or, more accurately landing zones, were code named Sword (British), Juno (British), Gold (Canadian), Omaha and Utah (both U.S.). (Crossword puzzle aficionados looking at the map will immediately recognize Caen and Saint-Lô – two favorites of puzzle constructors though the latter usually appears in the grid as STLO.)

Interestingly, the reason a particular code name was chosen for each zone has been more or less lost to history though there is some evidence for some of the names and reasonable speculation for others.

One report suggests that the three Commonwealth sectors were originally named for fish – goldfish, jellyfish, and swordfish but that Churchill, aware of the likelihood of significant casualties didn’t want Commonwealth soldiers dying on a beach called Jellyfish and ordered the change to Juno.

Another suggests a certain linguistic purpose to the choice. The names of the five sectors Utah, Omaha, Juno, Sword and Gold each have distinct pitch sequences as well as distinct sequences of vowels. Even with limited or disrupted sound transmission, they would each be readily distinguished by Americans, Canadians, and British. In addition, their letters are all readily distinct in Morse code and they do not make up an identifiable quintet.

There’s an interesting story in the Omaha World-Herald about the origin of the names of the two American sectors. A letter found in the effects of Gayle Eyler by his son asserted that General Omar Bradley,

code-named one of the two U.S. landing areas in Normandy as Omaha Beach in his honor, Eyler wrote, in recognition of his hard work “getting the place ready in a hurry.’’

The second U.S. beachhead, Eyler wrote, was similarly designated Utah for another carpenter on Bradley’s staff — a man who hailed from Provo, Utah.

The story offers another possibility

Bradley had a personal driver who took care of his uniforms and also cared for two fox terriers the general took with him all across Europe.

The dogs, Eyler wrote, were named Omaha and Utah.

The story details some of the investigative work that the World-Herald did to verify both accuracies and inaccuracies in Eyler’s account. It’s worth reading for the curious.

Our bus rumbled past Juno Beach

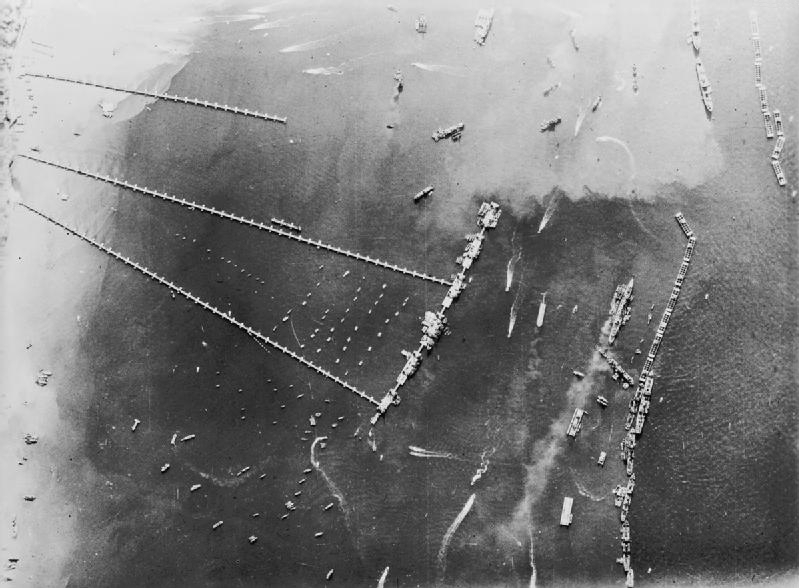

just a few minutes before we arrived at Arromanches and Gold Beach. Arromanches became particularly important to the Allies because at the outset of the invasion it was one of two assembly points for the Mulberry artificial harbours. (I use the British spelling of harbour since these engineering marvels were developed in the UK.) These were temporary jetties of prefabricated concrete supports, steel spans, and floating piers that were towed across La Manche in sections and aligned perpendicularly to the beach. The other Mulberry harbour was set up at Omaha Beach but, because it hadn’t been anchored to the sea floor as securely as its counterpart at Arromanches, it survived just a few weeks before it was so severely damaged by a storm that it was abandoned. From the air, the Arromanches harbour looked like this:

(Photo from Wikimedia)

In order to establish the harbour, engineers had to create sheltered waters. They used two methods to establish breakwaters. The first consisted of scuttled ships called Corncobs and the sheltered waters they created were called Gooseberries. Each of the landing zones had its own gooseberry and it was the gooseberries at Arromanches (Juno) and Colleville (Omaha) that grew into Mulberries. Sixteen ships were sunk to create the gooseberry at Arromanches.

In the photo above, you can see objects that are arranged parallel to the beach and perpendicular to the floating roadways. These are called Phoenixes. They are reinforced concrete caissons weighing between 2,000 and 6,000 tons. In preparation for the attack, they were built in England and sunk off the shores at Dungeness and Pagham. They were then refloated (hence the name Phoenix) under the leadership of an American Navy captain, Edward Ellsberg. Each caisson was towed to Normandy by two tugs and, together with the Corncobs, served as breakwaters for the Gooseberries at all the beaches and for the Mulberry harbours at Gold and Omaha Beaches. Some of the Phoenixes are still visible from the shore.

Closer to sea level, the floating roadways (known as Whales and the supporting pontoons called Beetles) looked like this:

(From Encyclopedia Britannica)

I can’t speak to the harshness of the storms in 1944 but the weather in Arromanches on the morning of 29 April 2018 did provide us with at least a sample of the sort of weather the soldiers and the harbour had to endure. With the temperature in the single digits, rain that varied from a tolerable drizzle to a pelting downpour, and winds gusting between 40 and 50 kph it made taking even a few photos like these and the one of the remains of the Phoenixes above something of a challenge.