It’s Thursday morning and we’re about to set off on a three-and-a-half-hour bus ride from the Hotel Rosario La Paz to the Hotel Rosario Lago Titicaca. Yes, the two hotels have the same owners and, for me, this turned out to be a fortunate development. But for you my three-and-a-half-hour bus ride means reading about the geological forces that lifted the Andes Mountains to their impressive heights – or not. It’s your choice.

Long Tall Andes.

Stretching 7,000 kilometers, the Andes Mountains are considered to be the longest mountain range on Earth’s surface. The range quite literally spans the entire south-north length of South America. In fact, although they may not immediately evoke images of craggy mountain peaks, several islands from the Isla de los Estados off the southern tip of Tierra del Fuego to Aruba and Curacao in the north, are surface manifestations of submarine extensions of the range. For some perspective, the Rocky Mountains of North America span a mere 4,800 kilometers and the mighty Himalaya range a comparatively paltry 2,300 kilometers.

Speaking of the Himalayas, let’s talk about how you measure the highest mountain on Earth.

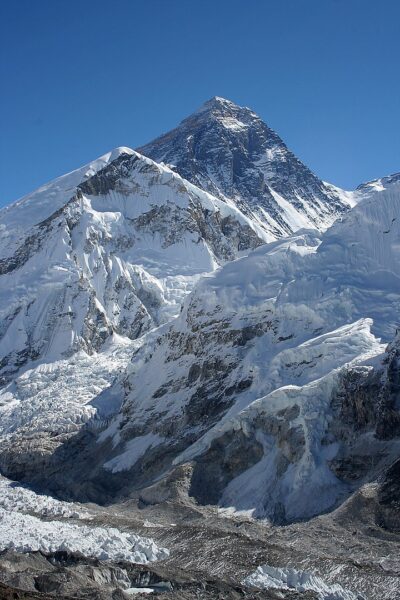

[Photo from Wikipedia – By Pavel Novak – Pavel Novak, {{Own}} father of User:che, took this picture and gave User:che permission to upload it under a free license, CC BY-SA 2.5.]

We all know the one in the photo above – the mountain the Nepalis call Sagarmatha, Tibetans call Chomolungma and we in the west call Everest is the tallest mountain on the planet, right? After all, it soars 8,848 meters above mean sea level and using sea level for the base measurement makes sense because we humans are terrestrial creatures. But what if we measure from a different starting point?

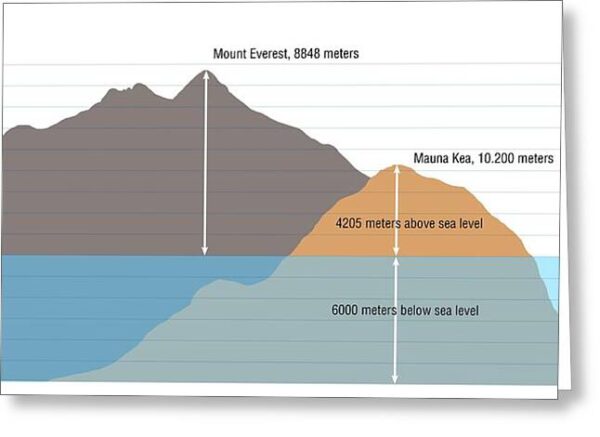

For example, would Everest remain the tallest if we started our measurement from the mountain’s base on the seafloor? The answer, as I’m sure you suspect, is no. We’d have to bestow that honor on Hawai’i’s Mauna Kea. As this graph from Tales of Hawaii shows,

although the 4,205 meters of this mountain that are above sea level reach less than half the height of Everest’s peak, the total height of Mauna Kea measured from its base on the seafloor is 10,210 meters or roughly 25 percent taller than Everest.

But what about this mountain?

[From Wikipedia By Dabit100/ David Torres Costales Riobamba – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0.]

You see, another alternative is to start our measurement from the Earth’s core and this provides yet a third result. The Earth has a significant bulge at the equator (the older you get, the harder it is to get rid of that stubborn fat around your middle) and, accounting for that, Mount Everest would only eke into the final spot on the top 10. The summit farthest from the core of the planet is Mount Chimborazo (seen above) in the Ecuadorian Andes. Although its elevation is only 6,263 meters above sea level (MASL) it is more than 6,384 kilometers from the core edging the second place finisher, the south summit of Mount Huascarán in Peru by a mere 10 meters. In fact, just as the Himalayan range holds most of the highest peaks above sea level, eight of the 10 summits farthest from the core are in the Andes. Because it’s too distant from Earth’s equatorial bulge, the peak in the chain that rises the highest above sea level, Argentina’s Mount Aconcagua at 6,962 MASL, is not on this list.

Let’s get ready to sub-duhhhhhhhhct!

For those of you who scaled the orogenesis of the Rocky Mountains on my 2017 trip through Alberta and a few states in the American west, this section might sound vaguely familiar but I won’t presume any foreknowledge for those who didn’t read that journal or (“Say it ain’t so, Joe!”) those among you who have forgotten that lesson.

Let’s start with orogenesis or the related term orogeny. The word combines two roots from Greek – oros meaning mountain and genesis meaning creation. Thus, orogenesis is simply mountain creation. Orogeny happens when the Earth’s crust is deformed by plate tectonics – usually requiring the movement of at least two plates.

In the case of the Andes, we met one of the plates while we were traveling on the east coast of the continent. That would, of course, be the South American plate. Now it’s time to introduce the other plate: “Ladies and gentlemen, moving east toward the South American plate at a recently measured rate of 79 millimeters per year I give you the Nazca oceanic plate.”

[Map of Pacific plates by Alartaristarion from Wikimedia Commons.]

When the edge of an oceanic plate slides sideways and underneath the edge of a continental plate because the former is denser, the process is called subduction and it’s the most common mountain building process on our planet. In much the same way that the hood of a car folds up when it collides with a wall, the Earth’s surface folds when two plates tectonically collide. The mountains that rise from these collisions are called fold mountains. (If you’re interested in a relatively simple discussion of different mountain types drop by this post from my 2017 trip.)

Although the subduction process began about 140 million years ago, the Andes themselves are considerably younger. In fact, recent studies indicate they may be as young as 45 million years and this would likely make them the youngest mountain chain on Earth. Two new techniques – one using physics and 3D modeling of tectonic movement and another using temperature – have contributed to an Andean picture that portrays a young mountain range characterized by rapid (meaning over a few million years) periodic growth spurts rather than a slow and steady gradual uplift. This recent analysis has been controversial but it has been gaining greater geological traction. That ends today’s lesson on orogenesis.

Thor Heyerdahl in Bolivia?

When I traveled through the American west in 2017, I made a point of stopping at what we call roadside attractions such as Keepers of the Wild that I mentioned in one of my posts about Iguazú. These are not the sorts of places where tours generally stop so I was a bit surprised when, a short time after we had our first glimpse of Lake Titikaka, our van turned at this sign

because, while I knew of Thor Heyerdahl and his Kon-Tiki expedition, I had no recollection of it having anything to do with Bolivia. And, in fact, it didn’t.

Kon-Tiki was a raft made of balsa wood, constructed in Peru with a design based on drawings of Inka rafts that the Spanish made in the 16th century. Heyerdahl believed that there were ancient connections between South America and Polynesia and there was enough archaeological evidence available at the time to at least give some credence to the theory. In 1947, Heyerdahl and a crew of five sailed west from the coast of Peru on a large raft he’d named Kon-Tiki. They completed an 8,000 kilometer crossing of the Pacific Ocean before crashing at Raroia an atoll in the Tuamotu archipelago. He recounted the story in his 1948 book The Kon-Tiki Expedition.

But the inquisitive spirit of the Norwegian adventurer didn’t stop at this journey. In the mid-1950s, Heyerdahl did extensive archaeological work on Rapa Nui (Easter Island) probing possibly deeper ties between Polynesia and South America. Then, in the late sixties he began a project to sail the Atlantic to prove that, just as there could have been contact across the Pacific, there could have been contact between ancient Egyptians and the Americas.

Heyerdahl’s first attempt using a boat built of reeds from Lake Tana in Ethiopia launched from the coast of Morocco in 1969. It began taking on water and broke apart after sailing about 6,400 kilometers failing by a mere 160 kilometers to reach any of the Caribbean Islands. His team later discovered that rather than being a failure of material, the attempt failed because they had omitted a crucial step in the Egyptian boat building method.

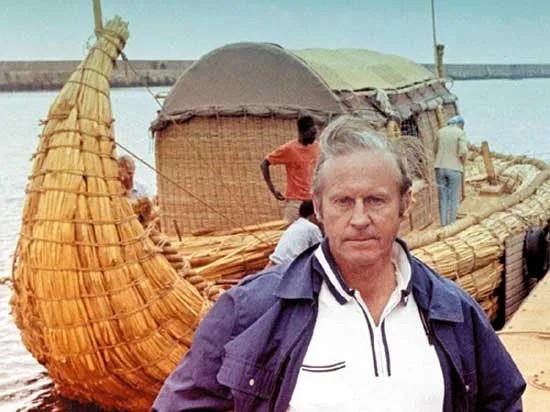

[Photo of Heyerdahl and boat from Encyclopedia Britannica.]

Making a bit of a leap, Heyerdahl turned to the denizens of the Lake Titikaka region who had great expertise in building reed boats because they had maintained an ancient tradition dating back centuries using the totora reeds native to the lake. The second expedition in a boat named Ra II reached Barbados and demonstrated that African mariners could have sailed west long before Columbus or the Vikings. The success of this Heyerdahl expedition could also lend some credence to hypotheses about the figures found on the art at Tiwanaku.

Paulino Esteban, one of the Aymara boat builders, sailed with Heyerdahl. Afterward he returned to his home where he established this small museum and continued building boats until his death in 2016. We met his son Fermin who continues the family tradition. The Ra II is in the Kon-Tiki Museum in Oslo.

In the next post, we’ll take a look at whether Lake Titikaka is, indeed, the highest lake in the world.