The previous series of entries took a rather brief (though for some, perhaps too lengthy) look at the forces and processes that created the mountains and lakes of Banff National Park. Before I turn my focus to a different shaper of the environment, I’ll take a step back and share some of my impressions and experiences of the town of Banff starting with its name.

Those of you who are either American history or railroad buffs or who read my Utah journal know that the U.S. completed its first transcontinental railroad on 10 May 1869 at Promontory Utah. Some 14 years later, in 1883, Canada completed its transcontinental railroad at Banff. This was rather remarkable since the Confederation of Canada was established a mere 16 years earlier in 1867.

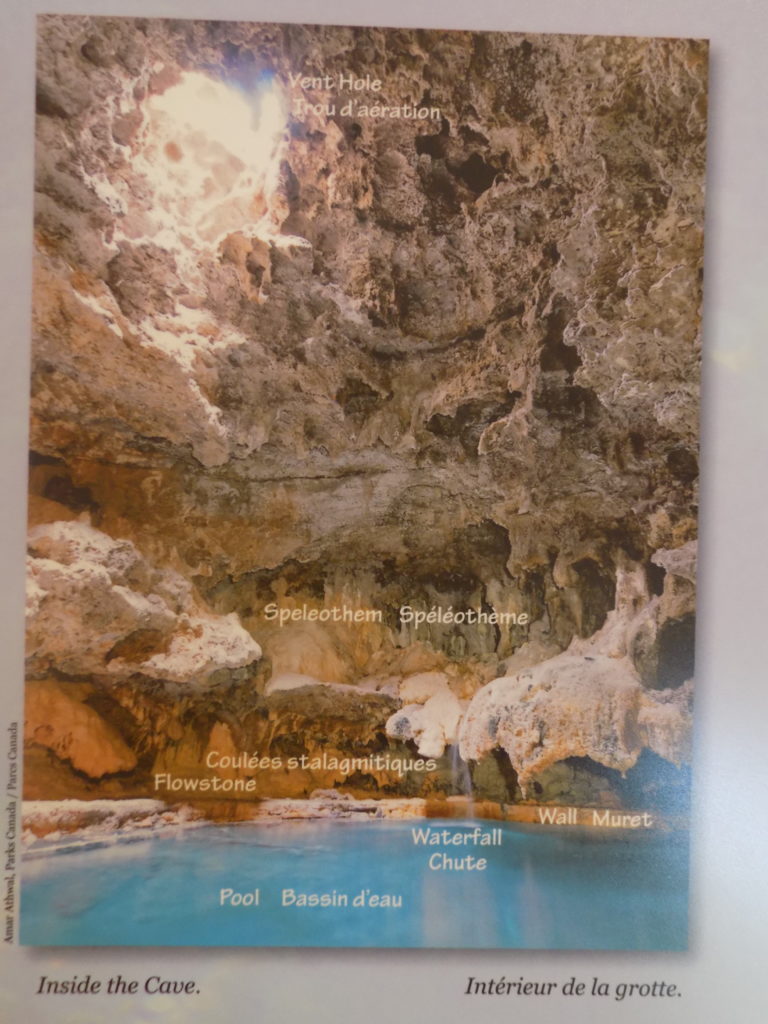

Sometime during 1883 three railroad workers happened upon a series of hot springs in the area of Sulphur Mountain that’s now called the Cave and Basin National Historic Site. This became the core of today’s national park and I’ll recount that history in some detail further along in this journal.

For now, I’ll note that in 1885 the federal government set aside 26 square kilometers surrounding the hot springs that would eventually become Banff National Park.

Needless to say (but I’m saying it anyway), the completion of the railroad was widely celebrated. In 1886, realizing the potential of the hot springs as a tourist destination, the government appointed a man named George Stewart to create an infrastructure of roads and services. Stewart chose the name Banff after Banffshire, Scotland to honor two of the directors of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR), George Stephen and Lord Strathcona, who had been born there. (The town of Banff, Scotland is about 74 kilometers north of Aberdeen on the northeast coast of Scotland and Banffshire is nestled between Aberdeenshire and Moray.)

Because of the delay at the rental counter, once I got started on my drive from Calgary, I determined that the only practical stops would be a brief one in the town itself and, perhaps, a quick look at Lake Louise. The town of Banff is interesting in a few ways. First, it’s one of only two municipalities located within a Canadian national park. (The other is Jasper in that eponymously named national park.)

Second, although it’s quite small at just 3.93 square kilometers, Banff sits at 1,383 meters elevation making it the highest town in Canada. (For a size comparison, the island of Manhattan occupies roughly 15 times more area than Banff.) It has a fairly static population of about 8,400 permanent residents with another 1,000 or so permitted if they are employed in the park for at least 30 days. Every resident of Banff must meet the “need to reside” requirement managed by the Canadian government.

I found the town itself quaint and charming though I doubt I would find it so in, say January, when it receives less than four hours of daily sunlight and the average daily high temperature is -6°. (Note, as is my custom, I will use the locally preferred measurement systems. Thus in Canada I’ll report distances using the metric system, temperatures in Celsius, etc. while in the U.S. I will switch to miles and Fahrenheit.) Perhaps you can see its charms, too.

More in the heart of town, it looks like this.

In addition to shopping and dining in town, I suspect many visitors to Banff will spend time at Cave and Basin (as will I, Monday) or in the Cascade Gardens that surround the town’s Tudor and Tudor Revival style administrative building (the vantage point of the first photo in this group) or even at the Buffalo Nations Luxton Museum (which had been on my itinerary before my airport delay).

I made a quick drive to the east side of town to get a quick peek at the Banff Springs (Now Fairmont) Hotel.

According to my movie locations guide, Marilyn Monroe stayed here when filming River of No Return which used Banff and the Bow River for some of its locations and the hotel, together with Betty Grable, appeared in Springtime in the Rockies.

According to my movie locations guide, Marilyn Monroe stayed here when filming River of No Return which used Banff and the Bow River for some of its locations and the hotel, together with Betty Grable, appeared in Springtime in the Rockies.

However, my one must stop was back toward the west side of town at the Banff Indian Trading Post. Now, those of you who know either that I have been gradually decluttering and divesting myself of many of my material possessions, or who know that I am not much of a souvenir collector might wonder why I’d be motivated to stop at a trading post. Well, it was to see the

Merman, of course. Here are some of the other photos of the Merman and from the town of Banff.

Now it’s time to turn to that other shaper of the environment.

The people of Banff

The official history of western Canada starts in the 18th century when Europeans brought horses, guns, and smallpox to the western plains with the latter killing about 60 percent of the native population. While the first Europeans crossed Arizona in the 16th century, the best evidence indicates that Anthony Henday was the first European to reach Alberta when, as an employee of the Hudson Bay Company, he camped with a band of Cree near present day Edmonton for the winter of 1754-55 thus becoming the first European recorded to have set foot in the Canadian Rockies.

In 1857, John Palliser led a three-year expedition on behalf of the British government to see if the land could be settled. Curiously, it wasn’t until 1882 that Tom Wilson, a CPR packer, led by a Stoney First Nations tribesman, became the first European to see the lake he called Emerald Lake and that was later named Lake Louise in honor of the fourth of Queen Victoria’s five daughters.

In 1883, the three railway workers I mentioned above, William and Thomas McArdell and Frank McCabe “discovered” the hot springs and by 1885 the Canadian government set aside those aforementioned 26 square kilometers as a federal reserve. Two years later, the government increased the area to 673 square kilometers and created “Rocky Mountains Park” making it the third national Park in the world. Over time, the park expanded to its current 6,641 square kilometers and had its name changed to Banff.

However, First Nations people inhabited the area long before the Europeans arrived. In fact, archaeological evidence indicates that humans have lived in and around Banff for at least 12,000 years. The park is located in the traditional territory of the Stoney, Kootenay, Blood, Piikáni (commonly called Peigan in Canadian English), Siksikáwa, and Tsuu T’ina First Nations peoples. (In lieu of the term Native American or American Indian, Canadians use First Nations to identify most of the people who lived south of the Arctic prior to the arrival of Europeans. People of the Arctic are called Inuit.) These groups, primarily hunter-gatherers, hunted game such as sheep, goats, moose, deer, and elk found in the Rocky Mountains.

As is the case with most First Nations peoples, most of their history is preserved through oral traditions. However, physical evidence of the lives of these earliest native people can be found in the petroglyphs and pictographs along the Milk River that runs through Writing-On-Stone Provincial Park which is about 40 kilometers east-northeast of Sweetgrass where I’ll cross the border into Montana. It’s claimed that this is the largest concentration of First Nation petroglyphs and pictographs on the great plains of North America. This evidence, together with a 10,000-year-old spearhead found in Athabasca demonstrate a lengthy and well-established way of life for the First Nations in Alberta.

In truth, archaeological sites can be found throughout the province. Within the confines of Banff National Park alone one can find more than 700 archaeological sites containing artifacts that provide evidence of the presence of Aboriginal campsites, butchering sites, quarries, mining towns, and historical dumps. These sites are both pre and post contact with Europeans. Unlike what I discovered about their counterparts farther south, if these natives formed more permanent pre-contact settlements, little if any evidence remains.

Note: In keeping with my 2022-2023 reformation of the blog into shorter entries, backdated to maintain their sequence, any comments on this post might pertain to its new configuration. See the explanation in the post Conventions and Conversions.

Thanks so much for all the sharing you do–these are amazing pix and fun reading!

Thanks, Jennifer. I appreciate comments. A lot!