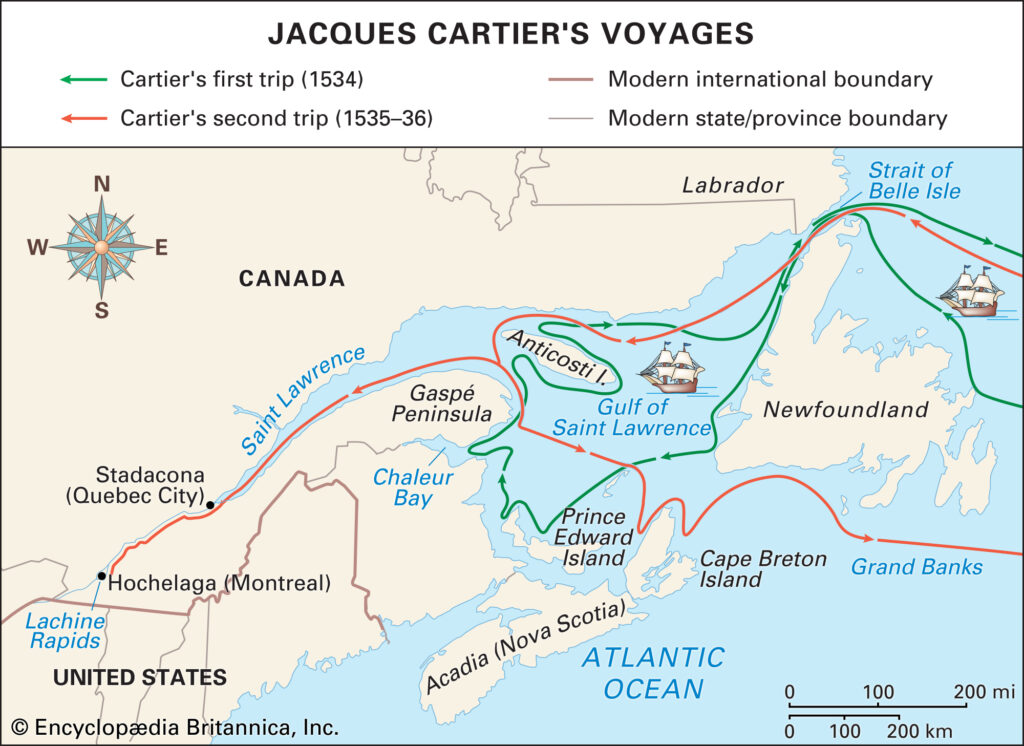

As I noted in the first post about Montreal, Jacques Cartier was the first European to have contact with the Haudenosaunee in 1534. He reached what is now Montreal on his second voyage in 1535 in what would have been considered Kanienkehaka (Mohawk) territory.

[Map from Encyclopedia Britannica.]

By the time of Cartier’s arrival, the tribes that had banded together as Haudenosaunee had settled into a peaceful coexistence living mainly as horticulturists. Their still fortified villages generally consisted of a number of longhouses each housing different clans with matrilineal social governance.

(The Haudenosaunee view the longhouse as a metaphorical description of not only their political alliance but also as a symbol of social and cultural comity. Thus, the Great Law of Peace becomes not only a political document but a social and cultural one as well.

Typically clans have animal names like Bear, Wolf, Turtle, or Hawk attached to them and members of a clan were considered family regardless of their tribal birth or allegiance. Today, many Haudenosaunee people continue these traditional systems and will thus identify themselves first by their clan and then by their nation. When in need of guidance they will look to the chiefs and the Clan Mothers who chose them.)

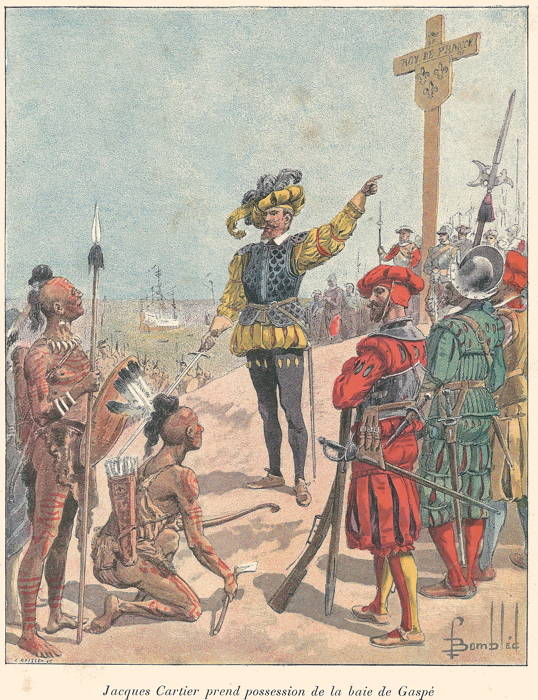

Relations between the First Nations and the Europeans didn’t have the most promising of starts when Cartier erected a cross in present day Gasp├® proclaiming the territory as New France

[Image from Wikimedia Commons Histoire de la Nouvelle France, Euge`ne Gue┬┤nin, 1900, Public Domain.]

after which he effectively abducted two tribesman from the settlement of Stadacona┬Ā – the sons of the chief Donnacona according to some reports. Cartier eventually used them on his second voyage as “guides” as he sailed up the Saint Lawrence to Holechaga or present day Montreal.

From this time into the middle third of the seventeenth century, relations between the Haudenosaunee and the French were perhaps not cordial but were certainly civil and based mainly on trade. However, as the British and Dutch began their own expansion into North America in the early part of that century, the tribes of the Confederacy became more deeply involved in the European fur trade providing animal pelts – principally beaver and deer – to the British and Dutch in return for iron tools, firearms, and other items. As some tribes increased their trade with the British and Dutch, it provided an opportunity for the Huron-Wendat and Algonquin tribes to expand their trade with the French.

These tribes and the tribes of the Confederacy had viewed one another belligerently for generations. Mix in the competition between the European powers and the situation had an inherent combustibility waiting for a spark of ignition.

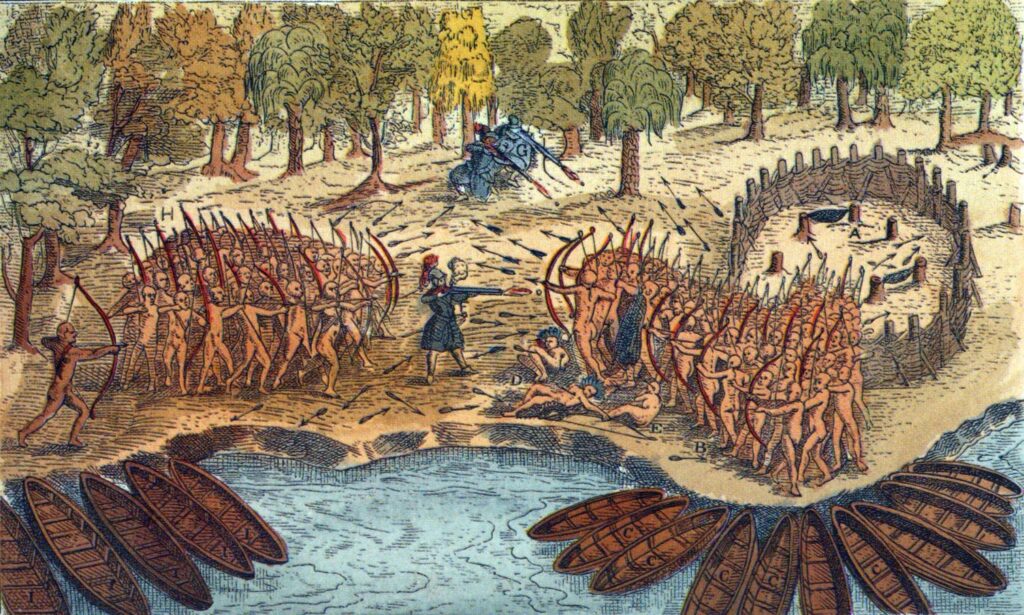

By the middle of the 17th century, the Haudenosaunee had overhunted the beavers in their traditional territory and began an aggressive attempt to expand it. Well armed because of their trade with the British and Dutch, the Kanienkehaka and Oneyoteaka began raiding Algonquin territory in the Ottawa Valley and by the 1640s were attacking New French settlements throughout the Saint Lawrence Valley. The French began fortifying their settlements – including at Montreal – and tried arming their Huron-Wendat and Algonquin allies.

The conflict also known as the Beaver Wars continued in fits and starts with the Haudenosaunee signing peace treaties with the French in 1653 and, after renewed hostilities, again in 1667.

[Image from Canadaehx.com.]

This treaty allowed the French to expand their trade and settlements both in the north, through the Great Lakes, and south along the Mississippi River while the Haudenosaunee displaced or absorbed other first nations as they greatly expanded their hunting grounds to include most of present day Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, and much of Illinois. Meanwhile, all of this took place against the backdrop of a broader conflict between the French and the English.

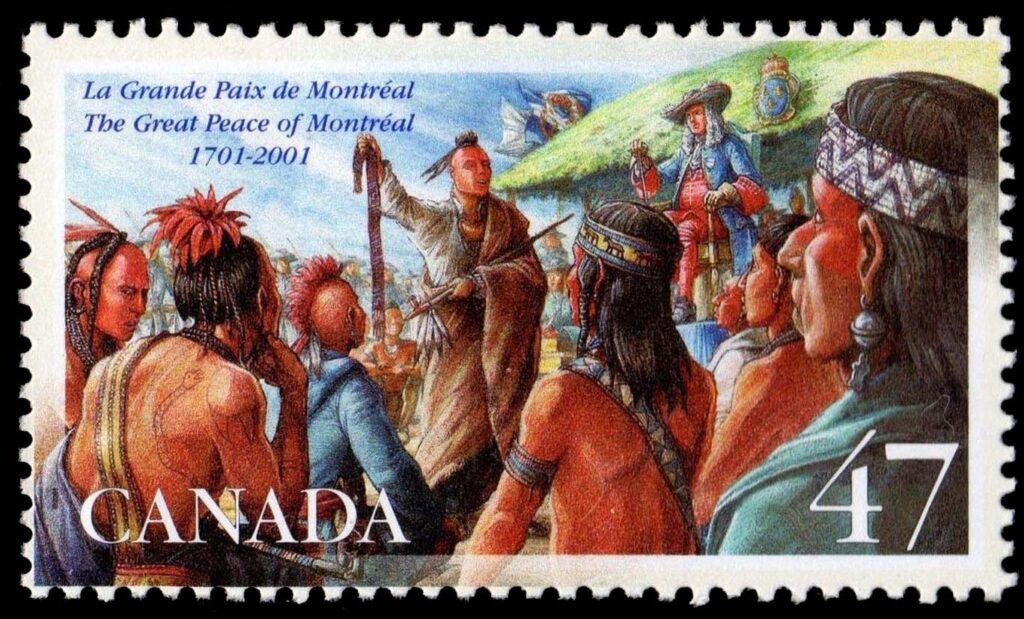

On 19 July 1701, the Haudenosaunee signed an agreement with the British known as the Albany Treaty ceding these lands to the English Crown while retaining hunting rights. However, the French, mainly through their alliance with the Algonquin also had a claim to the same territory. A few weeks later, on 4 August 1701, the French and the Haudenosaunee signed a treaty known as the Great Peace of Montreal.

The treaty granted the Confederacy what today we might call most favored nation status allowing them to trade freely and to acquire French goods at favorable costs. The price the Haudenosaunee paid was allowing a settlement at Detroit and their promise of neutrality in any wars between the French and the British. And those wars would not be long in coming.

While there were minor skirmishes between all the parties, all the fires remained controllable for about five decades before bursting into the flames of what has been called by some World War Zero.┬Ā As Great Britain clung to its 13 colonies along the east coast, the French claimed control over Canada and the Great Lakes. The focal point of the conflict was the upper Ohio River Valley with the French and their allies holding sway.

An incident involving a young George Washington led to his only military surrender. It came at the Battle of Great Meadows and triggered a full fledged war between the British, the French, and various indigenous tribes.

(On 28 May 1754 Washington and his Indian allies had successfully ambushed and defeated Joseph Coulon de Villiers de Jumonville and his French Canadian forces at the Battle of Jumonville Glen. They took a number of French as prisoners of war including Jumonville. An Iroquois chief named Tanacharison unexpectedly tomahawked Jumonville to death and he and his tribesmen scalped another nine. One man managed to survive, escape, and report the massacre to the French.

Their counter attack became the Battle of Great Meadows. Washington was in a topographically disadvantageous area and though he attempted to fortify it – what he called Fort Necessity – the weather and an unexpected French battle strategy led to his ultimate surrender.┬Ā

[Photo from Wikimedia Commons – By ScottyBoy900Q CC By SA-3.0].

It was essentially the truce document that Washington signed that helped enflame the broader war. Written in French, it contained not only the terms of surrender but, unbeknownst to Washington, a confession that he had assassinated Joseph Coulon de Villiers.)

Eventually, as William Pitt began financing not only the Prussian Army as it faced off with France in Europe but also reimbursing the British colonies in North America for raising armies to beat back the French, the British began piling up victories beginning with the battle at Louisburg in July 1758.

The British forces would march forth from the newly minted Fort Pitt (which replaced the French Fort Duquesne) and on to Quebec where they emerged triumphant in the Battle of Quebec in September 1759 before returning south to capture Montreal a year later.

The war came to an end with the 1763 Treaty of Paris in which the French lost all claims to Canadian territory though some of their social ethnocentrism persists to this day.┬Ā Neither the Treaty of Paris nor its later counterpart the Treaty of Versailles (1783) that ended the American Revolutionary War make any mention of the indigenous people.

Finally, for those too young to grasp the reference of the title of this post, I present this video:

FYI: The famous battle on the Plains of Abraham resulted in the British capture of Montreal, although Gen. Wolfe was killed in he assault. This battle sealed the British victory in the even Years War, which ceded Canada to England.

So much history. Pivotal in that war and worth looking at in depth, yes but I chose not to do so since that battle took place somewhat farther north than this chapter’s focus.

Always helpful to open more rabbit holes for people to dive into.