So, how did the canyon come to be?

Let’s return briefly to that figure of 70 million years ago. It was about this time that the North American Plate started to override the Pacific Plate and the Rocky Mountains began to form. (I assume that all of my readers have at least an awareness of plate tectonics as among the key forces that shape our planet.) As the plates shifted and overrode each other, a corner of what is now New Mexico and large areas of what is now eastern Utah, western Colorado, and northern Arizona rose from sea level to thousands of feet in elevation in a process called uplift. This formed the Colorado plateau. One of the unusual traits of this particular uplift is that the existing sedimentary layers tilted or deformed very little.

Now we can move forward to the time between six and seventeen million years ago when the Colorado River, compelled by gravity to flow downward, began seeking a path to sea level and the Gulf of California. Seasonal rains washed sparsely vegetated soils into the river and, carrying heavy sediment with no signs warning it to shift into a low gear, the steep gradient made the river a potent tool for erosion.

The main river begins to cut the canyon. Its tributaries then erode into the canyon’s sides thereby increasing its width. Softer rock layers erode more rapidly than harder layers above them. As they lose their foundation, the hard layers collapse and the cliffs and slopes that profile the canyon form. The forces of erosion also continue wearing away the ridges separating abutting side canyons exposing buttes and pinnacles and carving one grand canyon.

Even today, we can see these forces at work. This is a photo of Granite Rapids.

If you’d visited the canyon prior to 1984, you wouldn’t have seen these rapids because they didn’t exist. Their formation illustrates the relation between zones of structural weakness, tributary streams, debris fans, and rapids. Repeated flooding from nearby Monument Creek transported sediment that built what’s known as a debris fan. A river’s tributaries often follow zones of structural weakness thereby eroding a pre-existing weaker debris fan or passing through the bedrock wall if the wall is more erodible than the debris fan. This process can result in the formation of a pronounced meander and new rapids can form.

Fossils are okay.

Given the ages and exposure of its rock layers, it’s quite natural to expect that Grand Canyon is rife with fossils. If this is your expectation, you are correct. In fact, the canyon has three principal types of fossils – marine, terrestrial, and recent.

Let’s first take a quick and superficial review of how fossils form. To begin, that fossils form at all is often simply a function of random good fortune for fossil hunters. When most living things die, they are quickly recycled into nature by bacteria (through decomposition) and, to a lesser extent, by scavengers in processes that are especially true of the soft tissue such as flesh and muscle.

However, every now and then, a creature might die near water and its remains become buried in mud and silt. While the soft tissue still decomposes, the harder bones and shells, which are less susceptible to decomposition, get left behind and gradually buried under those layers of mud and silt. The sediment builds up and turns the bone into hard rock. As the layers of sediment increase, so does the weight and pressure on the “bone rock.” Ground water seeps in dissolving the bone and forming a natural mold that preserves the original shape.

If the water is rich in minerals, the minerals will, over time, fill the mold effectively forming a cast of the bone or shell in a process called permineralization. Over millions of years, geologic processes such as mountain building, earthquakes, and erosion lift the fossil to the surface and expose it.

Fossils can form through other processes such as freezing, desiccation, entrapment in substances like amber or tar (think La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles), and carbonization but the process of permineralization is the most common.

In the Grand Canyon, a prehistoric marine environment has laid down layer upon layer of sedimentary rock over the past 525 million years. Thus, marine fossils are quite common. Searchers have discovered stromatolites, trilobites, crinoids, brachiopods, bryozoans, and corals among other types of fossils.

If you look back at the table depicting the canyon’s three sets of rocks (in this post), you’ll see four layers in the blue section labeled as the Surprise Canyon Formation, Supai Group, Hermit Shale, and Coconino Sandstone. These rock layers are terrestrial rather than marine in origin. This is where you can find leaves, insects (mainly dragonflies), and animal tracks.

Finally, there are the recent fossils. Pleistocene and Holocene remains have been discovered within many of the canyon’s caves as have remains of even more recent animal habitat.

But no dinosaurs are allowed.

For all the fossils commonly found in Grand Canyon, perhaps the most notably absent are any relating to dinosaurs (unless you consider birds as descendants of the dinosaurs and choose to classify some of the recently fossilized condor bones as “related”). But, if you paid attention in the section about the Grand Canyon’s age, this absence should come as no surprise.

It’s true that the rock that makes up the canyon walls is incomprehensibly ancient. But the canyon itself, even if it’s as old as 17 million years, didn’t form until scores of millions of years after the dinosaurs became extinct some 65 million years ago. Hence, no dinosaurs allowed.

A few random facts approaching the end of the Trail of Time.

Weather or not.

You might have read that, from a microclimatic standpoint, mountains can create their own weather. They do this by forming a barrier for moving air that wind then pushes up the mountain to elevations where the air is cooler and the atmosphere thinner making the air pressure lower. Moisture in the air that was a gas at the higher pressure of the lower elevation then condenses forming clouds before falling as precipitation.

So it is with the sudden elevation changes in the Grand Canyon. The weather varies (or at least can vary) dramatically depending on where you are in the canyon. For example, the coldest, wettest weather station in the entire region is the Bright Angel Ranger Station on the North Rim, while the hottest (and one of the driest) is at the Phantom Ranger Station just 8 miles down the Kaibab Trail near Phantom Ranch.

A town so near and yet so far.

Just outside Grand Canyon, is the Havasu Canyon that has become part of the Havasupai (People of the blue-green water) Indian Nation. It’s roughly an eight-mile hike from Hualapi Hilltop to Supai Village near the floor of the canyon and this trail is the only access to the village. The Havasupai have lived in this place for at least 800 years. Many consider Supai village the most remote community in the 48 contiguous states and it’s the only place in the U S where mail is still delivered by pack mule.

No fishing allowed.

The Grand Canyon was once home to eight species of fish. However, only five of these species are found in the park today. The three missing species are Colorado pikeminnow, bonytail, and roundtail chub. Of these three, the first two are considered endangered. The five remaining species are humpback chub (endangered), razorback sucker (endangered), bluehead sucker, flannelmouth sucker and speckled dace.

The eight native species belong to only two families – minnows and suckers – and six of the eight are found only in the Colorado River Basin. Today, particularly close to the Glen Canyon Dam, (completed in 1963) the most common species are non-native rainbow and brown trout.

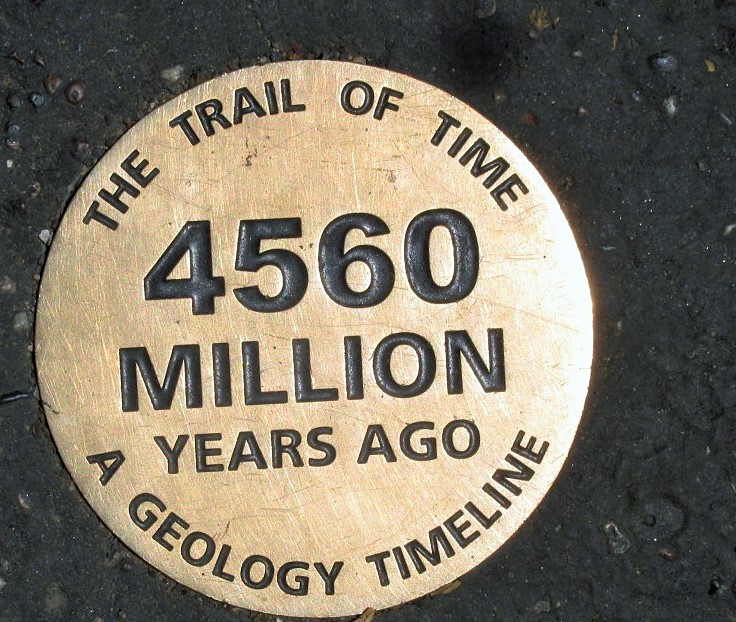

And now, we’ve reached Maricopa Point and the end of the Trail of Time. At the beginning of the walk, the embedded trail marker read 920 million years ago. We’ve now figuratively traveled back more than three thousand million years and the end of our temporal journey is signified by this marker.

I hope you feel you know the Grand Canyon a little better than you did when you set out with me.

More than six and a half miles lie ahead before I reach the western terminus of the south rim Trail at Hermit’s Rest.

For now, I’ll leave you to contemplate four thousand five hundred million years. What lies ahead of me for the rest of this day is physically exhausting. I’ll guess that what lies behind for you is a different sort of exhaustion acquired from reading this far. I’ll give both parties a break. I’ll have more to say about the Grand Canyon and my time there in my next entry.