Vancouver in the time before humans (Vancouver and Me supplement one)

Till we meet the first time – shaping clarity.

Sometimes elements of my research are a bit repetitive and routine. This can be beneficial because it pounds concepts I find difficult through my skull until they finally lodge at least semi-permanently in my gray matter. For example, understanding the vast times scales involved in tectonics minimizes the cognitive dissonance that arises trying to envision a tropical Canada.

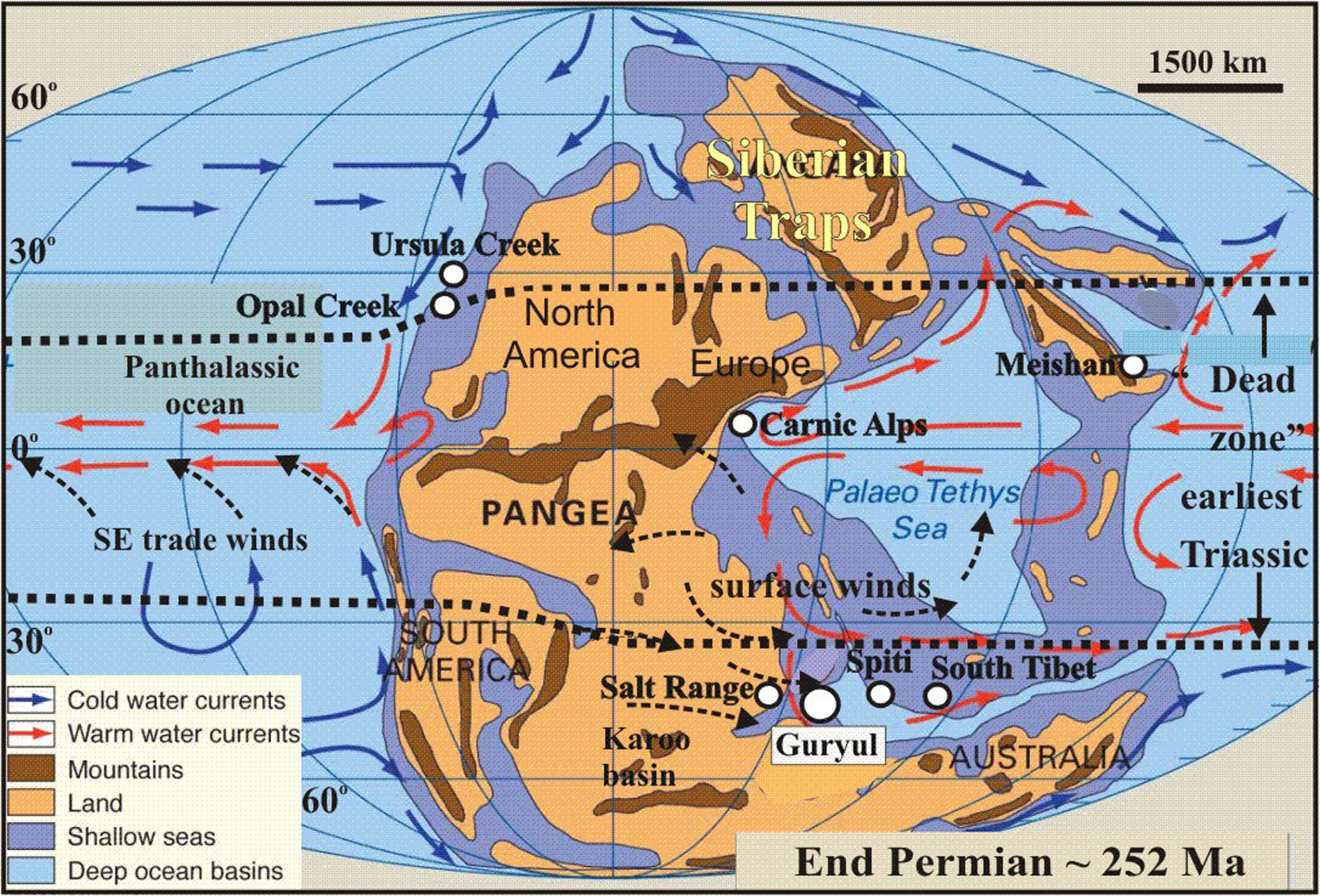

[From onlinelibrary.wiley.com.]

Specialized terminology that once seemed strange – orogeny, subduction, plutons, and the like – gains a measure of familiarity. And then, I start reading about a place like Vancouver and a new term arises that requires definition and research. That’s precisely what happened when I read the following, “the City of Vancouver is mostly on till” and I thought, “What in heaven’s name is till?”

The Encyclopedia Britannica, provided an answer. In geology, till is

unsorted material deposited directly by glacial ice and showing no stratification. Till is sometimes called boulder clay because it is composed of clay, boulders of intermediate sizes, or a mixture of these. The rock fragments are usually angular and sharp rather than rounded, because they are deposited from the ice and have undergone little water transport. The pebbles and boulders may be faceted and striated from grinding while lodged in the glacier. Some till deposits show limited organization of the fragments: large numbers of stones may lie with their long axes parallel to the flow direction of the glacier. This could provide more accurate information about flow direction than other glacial indicators. Although difficult to distinguish by appearance, there are two types of till, basal and ablation. Basal till was carried in the base of the glacier and commonly laid down under it. Ablation till was carried on or near the surface of the glacier and was let down as the glacier melted.

In some ways, this definition was something of a relief for me and it should be such for you. Given the necessity of glaciation, it should eliminate the need for yet another detailed discussion of plate tectonics. But that doesn’t mean I can ignore it completely.

Tectonics and Volcanism.

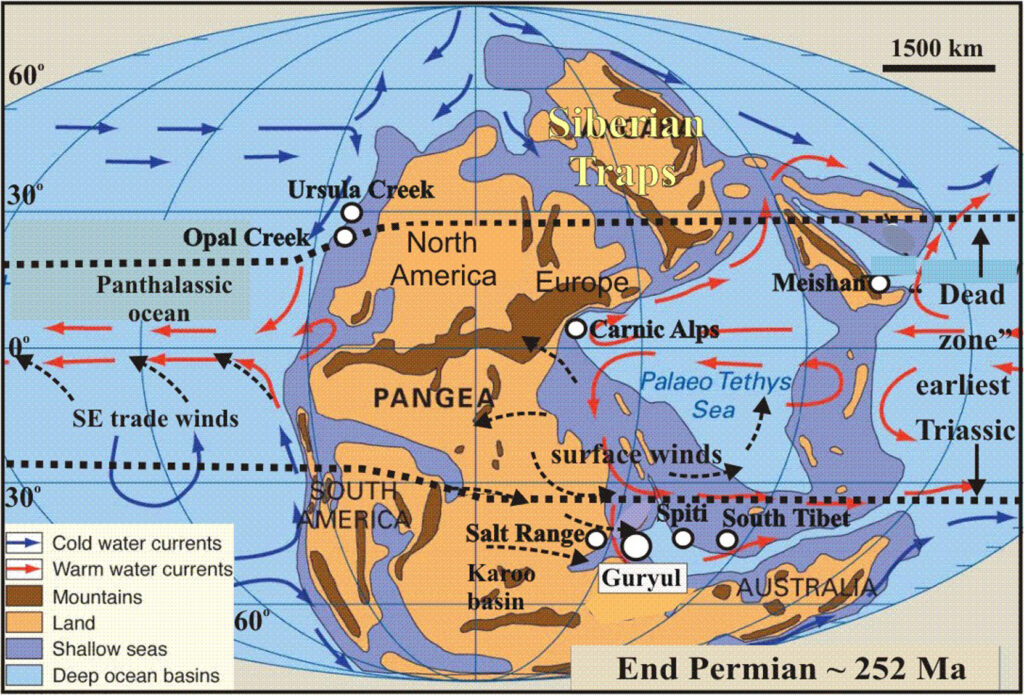

Those of you who read the paleontological-geological supplement on Japan might recall that the island chain is part of the Pacific Ring of Fire.

[Map from National Geographic and USGS.]

This time you need to focus on the side of the Ring that follows the west coast of the Americas from Chile north to Alaska. For the moment, let’s ask the WABAC machine to take us back about 200,000,000 years. The North American Plate had finally reached the stage where it was ready to strike out on its own from the supercontinent Pangaea. The land that would become the province of British Columbia was then close to today’s border between itself and Alberta.

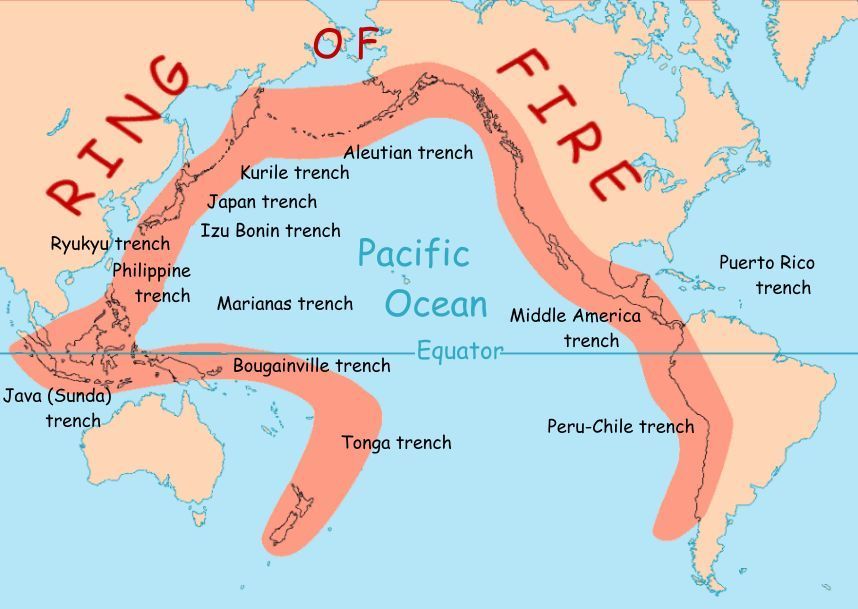

[Map from infoplease.com.]

As it migrated in a northwesterly direction, North America created a long-lived subduction zone where oceanic crust slowly sank beneath the new continent’s west coast. This brought two chains of volcanic islands, the Stikine and Quesnellia arcs, from proto-Asia ever closer to proto North America. About 180 MYA, the buoyant continental crust of the arcs collided with North America creating a new volcanic arc, the Omineca. Eruptions in the Omineca Belt generated enough magma to fuse the Intermontane Superterrane with the crustal fragments of North America becoming what is now eastern British Columbia.

(Paleontologists led the discovery of these collisions by identifying fossil species that are more akin to fossils in Asian rocks of the period than those native to North America. Geologists call these crustal fragments tectonostratigraphic terranes or simply terranes. When they see a repeated accretion of multiple terranes, they throw an S logo and a cape on it and call it a superterrane.)

Despite the force of this collision, North America continued its march toward the northwest. Some say that those who do not learn from history are doomed to repeat it. Such was the case for North America because some 60 to 80 million years later, another collision occurred with another island arc called the Insular Islands. Even the rocks found in the Insular Superterrane are not related to the rest of the North American continent.

[Wikimedia Commons By BlackTusk CC-BY-SA 2.0.]

(Although on the Ring of Fire, the BC volcanoes have been relatively quiet. The most recent eruption happened in Lava Forks – about 800 km [500 miles] northwest of Vancouver – some 150 years ago. There hasn’t been a major eruption since Mt. Meager exploded more than 2,300 years ago. One source posits at least 18 “sleeping” volcanoes in the province.)

Ice, Ice Baby Redux.

With this groundwork established, the WABAC can speed us through space and time to look at Earth’s northern hemisphere some 18,000 years before present (BP). Fortunately, the heaters on the WABAC are in good working order because what we see aren’t mere glaciers but ice sheets with Canada and much of the northern United States serving as the bed beneath. They are as much as two kilometers thick. (This is essentially what we saw when we were in London in this same time frame.)

There were two major ice sheets – the Laurentide and the Cordilleran – and the two merged at the Continental Divide. It’s possible that at its western end the pockets of refugia (places in which humans and other species survived this maximal glaciation) existed in the Cordilleran Ice Sheet. One of them is suspected to have been at the northern edge of Vancouver Island. However, the location of the city itself was well buried.

As the climate warmed and the massive ice sheets began to melt, it might have looked something like this:

Notice that within a mere three to five thousand years the Cordilleran had melted to the point that most of the coast was no longer under the ice.

Till – we meet again.

If you’ve sailed into the fjords of the Inside passage in Alaska or otherwise been to a place where you’ve seen a retreating glacier, you’ve seen till. When it still abuts the glacier, it’s called glacial moraine. When the glacier has abandoned it completely, it’s called till.

Watching the video above, you see the ice sheet retreat. As it receded, it was eroding the underlying rock by one of two processes – abrasion (the mechanical scraping of a rock surface by friction between rocks and moving particles during their transport by wind, glacier, waves, gravity, running water, or erosion) or plucking (when the melting ice at the bottom of the glacier infiltrates joints in the bedrock.) The ice sheet essentially acts like a giant bulldozer pushing up and carrying or leaving behind enormous amounts of sand, dirt, and rocks that, in this instance, underlie the city of Vancouver.

As the ice sheet retreated, it once again opened a path for the Fraser River. With its source in the southeast corner of Mount Robson Provincial Park, the Fraser is the longest river in British Columbia flowing for 1,375 km (850 miles) to its mouth at the Strait of Georgia at Vancouver. Much to the consternation of immigration services on both sides of this artificial boundary, its 50 km (31 mile) wide delta crosses the border into Washington State. No one on the American side has proposed a wall.

As you can imagine, the Fraser River (called Sto:lo in the Halkomelem language, Lhtakoh in the Dakelh language; and Elhdaqox in the Tsilhoqt’in language) played a critical role for the First Nations who have inhabited its environs for more than 10,000 years.

And we’ll discuss that in the next chapter.

-

It’s just a shot away – Prizren

March 6, 2026 -

Some things looking better, baby – Getting into Kosovo

March 4, 2026 -

Here, where the sky is falling – Kukës

March 2, 2026 -

That’s when we fall in line ’cause we got Berat

February 27, 2026 -

Walking on the big stuff – a climb to Tragjas

February 25, 2026