The newly shortened version of the previous post ended with confirmation that Mount Lemmon name honors Sara and not her husband John but we hadn’t yet reached its peak so let’s continue our ascent.

In addition to the changing scent, here’s something else that happens on that 27-mile drive. At the base of the mountain, most of the vegetation looks like this:

What you see is the Saguaro cactus, cholla, prickly pear, and mesquite trees that you expect to see in the southwestern United States. Ascending the mountain means passing through four more distinct life zones – starting with semiarid grasslands, to chaparral and oak woodlands where you also see manzanita and alligator juniper trees, to the gloriously scented ponderosa and Arizona pine forest that begins at about 8,000 feet. Upon reaching the summit you encounter Douglas fir, quaking aspen, and mountain ash trees – a remnant of the Pleistocene era. According to the U.S. Forest Service, the diversity of this 27-mile drive is akin to the diversity you’d encounter driving across the country from Mexico to Canada.

As you ascend, the air holds more moisture, the trees grow taller and the increase in tree height seems proportionate with the decrease in temperature. The mid ninety-degree temperatures at the valley floor dropped into the low seventies at the higher elevation.

In addition to the views, recreation, and trails, there’s also a small community called Summerhaven and an observatory at the top of the mountain. The International Dark Sky Association is based in Tucson and, while the city itself is not a recognized dark sky locale, they have taken steps to minimize nighttime light pollution. The observatory at Mount Lemmon conducts the Catalina Sky Survey which is a program designed to identify any potentially hazardous asteroids or other near-earth objects that may pose a threat of impact.

You can see more pictures of Mt. Lemmon here, if you’re interested.

Who was General Hitchcock and what army did he command?

Each week, one of my favorite NPR shows, Science Friday, features a segment called “Good thing, bad thing” because every story has at least two sides. This is the case for this variously named highway. The good thing should be obvious. Because of this road, thousands upon thousands of people have easy access to make this remarkable 27-mile drive that spans five life zones and 100 centuries while taking part in all the mountain has to offer.

But now let’s look at how the road was built. About nine miles from its starting point at Tanque Verde Rd., the Catalina Highway becomes the General Hitchcock Highway. So I’ll start by telling you a bit about Frank Harris Hitchcock. He was the chairman of the Republican National Party for two years beginning in 1908. From 1909 to 1913 he led an army of postmen as William Howard Taft’s Postmaster General where his major achievement was establishing the first U.S. airmail service.

When the Lemmons and E.O. Stratton summited the mountain in 1881, they encountered two men identified as Carter and W. Reed near the top. These hunters had built a cabin in what is now Summerhaven and planned to build a flume so they could send lumber to the growing city in the valley below. By the early 20th century some form of rudimentary road existed and when Hitchcock began his efforts to raise the funds and resources to construct an improved road, Summerhaven had become a popular destination.

(from Wikipedia)

Construction of the road began in 1933 and here is where the situation begins darken a bit. To ensure enough labor to build the road, Hitchcock used his political connections to broker an arrangement between the Bureau of Prisons, the Bureau of Public Roads, and the Arizona Highway Commission to establish the Tucson Federal Prison Camp at the foot of the mountains. His express purpose was using prison labor to construct the road.

With the outbreak of World War II, the darkness deepened. The first prisoners to arrive were mainly draft resisters who were eventually joined by 41 nisei – or second-generation Japanese – in what was now known as the Catalina Honor Camp. Their unpaid labor continued construction of the road during the war.

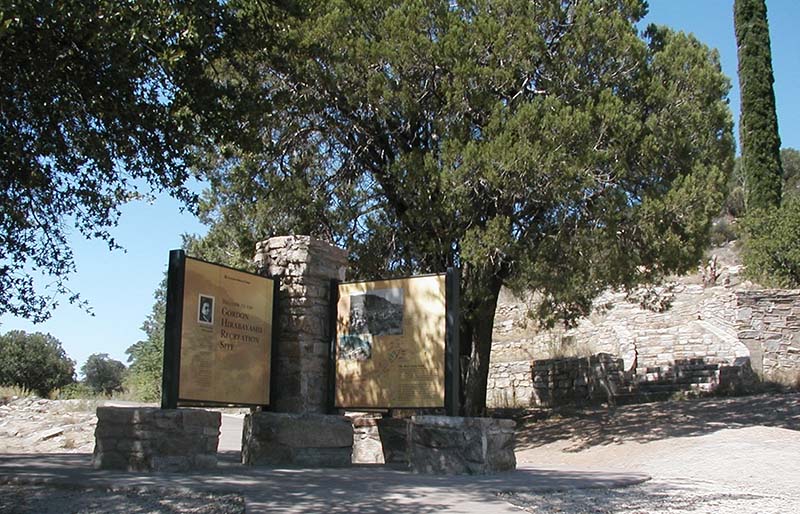

(Probably the most notable of those among the nisei was a man named Gordon Hirabayashi. After joining the American Friends Service Committee as a conscientious objector, he turned himself in to the FBI in 1942. He was sentenced to 90 days in prison but, with the backing of the ACLU, appealed his case to the Supreme Court which eventually upheld his conviction. He reported on his own to the camp where he served his sentence.

Hirabayashi later spent a year in federal prison at McNeil Island Penitentiary for refusing induction into the armed forces, contending that a questionnaire sent to Japanese Americans demanding renunciation of allegiance to the emperor of Japan was racially discriminatory because other ethnic groups were not asked about their adherence to foreign leaders.

In 1983, Peter Irons, a political science professor at the University of California San Diego uncovered documents that clearly showed evidence of government misconduct in 1942 -evidence that the government knew there was no military reason for the exclusion order but withheld that information from the United States Supreme Court. With this new information, Hirabayashi’s case was reheard by the federal courts, and the ninth circuit Court of Appeals overturned his conviction.)

The highway was competed in 1950 and named for Hitchcock who had died in 1935. In 1999, the site of the Honor Camp was converted into the Gordon Hirabayashi Recreation Area.

Now, let’s descend the mountain to find

Ghost horses in the middle of the road.

The speed limit on South Houghton Road on Tucson’s east side is 45 miles per hour and if you’re cruising along at or above that speed, you’ll likely miss one of the more unique works of street art in all of Arizona. The truth is, you need to pull into the lot of the Quick Mart on the corner of South Houghton and East 22nd Street, park and walk a half block or so to really get a good look at these ghost horses.

In fact, even if you were caught in heavy traffic and stopped beside the sculpture by Lauri Slenning called Mare and Foal, you might look at them and think they were rather unremarkable given that this is what you would see this:

However, if you park your car and walk toward them along the median strip, their appearance entirely changes:

To experience an even more remarkable disappearing act, pop into this folder where I’ve included some additional pictures of Rattlesnake Bridge and the horses including one I found on the artist’s website. I think that picture alone is worth the click.

I know I often share my gustatory adventures as part of my retelling but, in truth, none of the meals on this trip was particularly memorable. However, I’ll try to share noteworthy elements as I recall them. Two of them occurred on this first night when I had dinner at the Guadalajara Grill. The first was the trio of strolling musicians and the second was having fresh salsa prepared table side. Unfamiliar with what might be considered gastronomically hot in the southwest and out of an abundance of caution, I ordered the medium. This was a mistake. I should have gone for the spicy.