The first of the two major trips I have planned for 2017 will take me to Arizona and Utah – two of the five U S states I’ve never visited. I will cover two of the remaining three – Wyoming and Montana late in the summer leaving Hawai’i as the last state I need to visit to complete the set of 50. For this trip, I’ll arrive and depart from Tucson and will spend about a week in each of the two states.

My flight from BWI had an early morning departure and, after a transfer at Chicago’s O’Hare Airport, arrived in Tucson without incident. I picked up my Hyundai Accent – which, by trip’s end, would have nearly twice its beginning odometer reading of 4,060 miles – and started toward the city with directions provided by Google maps.

A few travel tips.

Let me jump forward in time but digress in subject matter. In general, Google maps proved to be a reliable guide and helpful resource. However, I’d also urge anyone planning to travel in the open spaces and back roads of the west to do so with a paper map as well (at least as of 2017). It’s certainly possible that some of the issues I encountered were attributable to my mobile provider (T-Mobile) but driving some of the state roads and two-lane US Numbered Routes I found myself without service for long stretches of time and distance. Sometimes work arounds were easy. Other times, not so much.

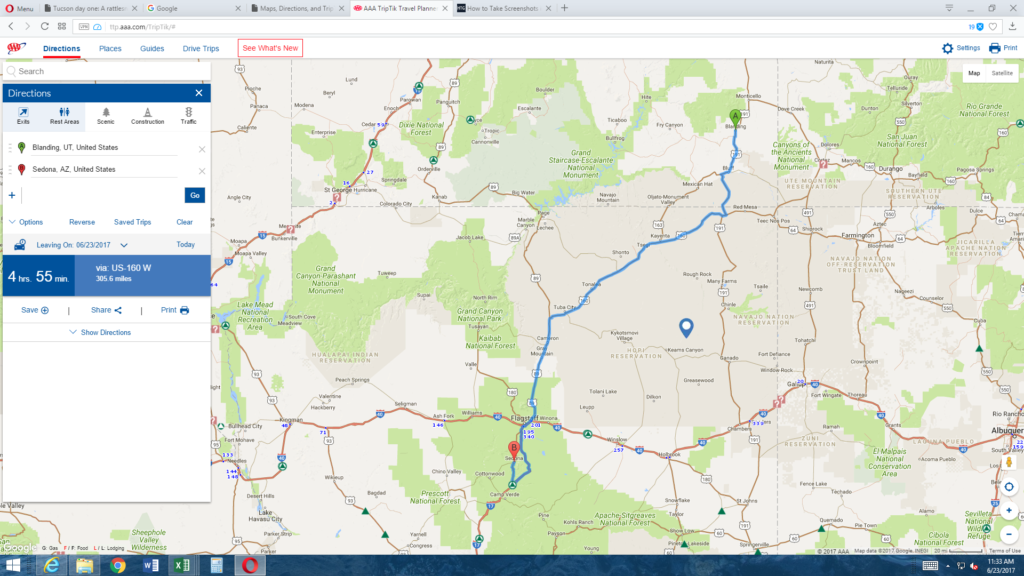

For example, prior to the trip’s final day, I downloaded directions to my phone while at a motel in Blanding, Utah. My plan was to drive from Blanding to Tucson with a stop in Sedona for lunch. The drive to Sedona was a mostly Interstate free route. I used the motel’s wi-fi to download the directions to my phone the night before my departure. Leaving Blanding, the signal was fine but as I traveled south on US 191, the GPS, while maintaining contact seemed to lose some of its synchronicity. By the time I passed southwest of Kayenta on US 160 toward Tuba City, the synchronization between my phone and the satellite warped even further and the verbal instructions from the phone began to precede my physical location by a half mile or so. Eventually, the disparity grew to nearly five miles, making awareness of my surroundings quite important.

While I’m offering tips about traveling in this region, I should add that it’s best to start the day prepared in other ways, too. By this I mean fill your tank and empty your bowels and bladder before you set out. Have a snack and water or some potable liquid in the car. You might need it. For example, once I left Blanding, the ensuing 80 miles or so had no gas stations, no rest stops and traffic in either direction was minimal. This is not uncommon on these roads.

My last tip is that if you’re traveling through Arizona in the summer, just ignore the time. Here’s the problem. Arizona remains on standard time year-round. So, when the rest of the U S is springing forward Arizona’s laying back. For all practical purposes then, Arizona is in the Pacific time zone. You can rely on that unless you’re in the Navajo Nation because this area does switch to daylight savings time putting you back in the Mountain time zone. You can rely on that unless you’re in the Hopi Nation inside the Navajo Nation because the Hopis do not use daylight savings time. Got it?

By the way, Utah makes the switch to daylight time so if you cross into Utah from Arizona you will “lose” an hour unless, of course, you’re crossing the state line from the Navajo Nation. You can rely on this unless you’re going to one spot in Glen Canyon called Dangling Rope because while the rest of Utah changes to daylight savings time, Dangling Rope doesn’t. Got it?

Arriving in Tucson.

Now, I’ll return to Tucson. For my first two nights I’d arranged a stay through Airbnb and, since I had a late afternoon check-in, my host Carolyn suggested I might want to take a drive up Mount Lemmon. But first, I wanted to get a look at the Rattlesnake Bridge. This pedestrian and cycling bridge (Tucson seemed generally friendly to both pedestrians and cyclists, by the way) crosses Broadway Boulevard near state route 210. Apparently, it was built with public arts funding as a high concept project. One report I read noted that, at one time, sensors lit the eyes and rattled the tail but that wasn’t the case on the day of my visit. (Please note that, if you want to see more pictorial details, you can see an uncompressed version of any photograph by clicking on it.)

After walking through the belly of the beast, I returned to my car and headed off toward Mount Lemmon.

Mount Lemmon sits a bit northeast of central Tucson in the Santa Catalina Mountains. It’s accessible by a single multi-named two-lane road that was 18 or 20 miles from my location at the bridge. The climb starts at Tanque Verde Road as Catalina Highway. At some point, the name changes to Mount Lemmon Highway then changes again to General Hitchcock Highway. The route is also known as the Sky Island Parkway and has been designated as a National Scenic Byway.

What makes Mount Lemmon zesty?

If someone took off in a parachute or parasail from the top of Mount Lemmon and could glide in a direct line to the starting point of the Catalina Highway, they would descend more than 6,000 feet and travel about 12 miles. If they rode a bicycle down the road, they would descend the same 6,000 feet but would travel 27 miles. What makes the drive up (or down) Mount Lemmon so fascinating is what happens over those 27 miles.

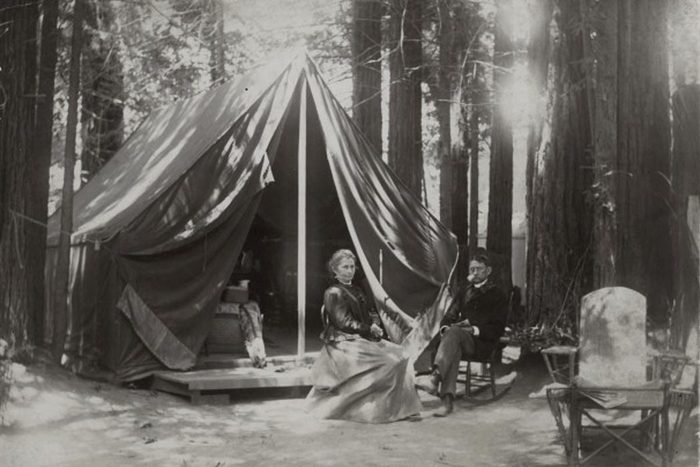

The mountain draws its name from Sara Allen Lemmon nee Plummer. Sara Plummer was a botanist and an adventurous soul who found a match in her husband John Gill Lemmon who was, like Sara, an adventurous botanist. While honeymooning near Tucson in 1881, the couple decided to try to scale the tallest peak in the Santa Catalina Mountains – called Babad Do’ag in the native O’odham language.

[Photo from the Santa Barbara Historical Museum via daily.jstor].

After several failed attempts, and hearing that the north face of the mountain wasn’t as steep as the southern side, the Lemmons enlisted the help of a local rancher, E O Stratton, who helped them find a path to the mountain’s summit. Along the way, the Lemmons collected several new species of ferns and flowering plants that John would later classify and, by doing so, earn his spot in the biology texts while conveniently overlooking the work his wife had done. (She was responsible for the designation of the golden poppy as California’s state flower.)

In addition to the ferns, when they reached the point where the mountain’s oak forest transitions to a pine forest, Mister Lemmon declared that he had located a new species of pine – Pinus Arizonica – distinguished by a preponderance of five fascicled needle bundles as opposed to the three needle bundles typically found on the Ponderosa pine that also populates the mountain.

The two pines are closely related and some botanists consider the Arizona pine a variant of the Ponderosa pine. Interestingly, the bark on Ponderosas changes color as the trees age. The younger pines have black bark that gradually turns yellow as the trees mature. Better still than this color change for people driving to the top of Mount Lemmon, is the scent the trees produce. Some people say you need to get up close and personal with the trees but for me, as I drove up the mountain with my windows open, the scent of vanilla was apparent. For some people, the smell is said to be more like butterscotch and for others, coconut. My guess is that however you perceive the scent, you’ll enjoy it.

Meanwhile, how do we know that Mount Lemmon was named for Sara and not John? For that we can thank Mister Stratton who noted contemporaneously, “From Carter’s camp we went to the highest peak of the Santa Catalina Mountains and christened it Mount Lemmon in honor of Missus Lemmon who was the first white woman up there.” A 1904 Pima County map formalized the name.

Note: In keeping with my 2022-2023 reformation of the blog into shorter entries, backdated to maintain their sequence, any comments on this post might pertain to its new configuration. See the full explanation in the post Conventions and Conversions.

Todd. The pictures of the ghost horses are so cool. I’ve done some traveling out west but have never seen the bridge or the horses. I guess I need to go back and do a little more sightseeing.

Thank you so much for sharing your newest adventure. Awesome!

Hi Todd,

Muchas gracias for sharing your adventures. Fascinating!

Pedro

I cant wait to show my son that bridge!

Sadly the artist responsible for the Invisible Horses and many other public works of art died a year following the horses finding their home. As a Tucsonan, I often drive out of my way to catch a iew of the mare and foal and the retaining wall sculptures.

I’m so sorry to hear that. I hope she (or he) had the chance to see that people appreciated them.

I apologize if I took too long to approve your comment. Since I haven’t been able to travel for more than a year, I expect mainly spam comments and don’t check the site daily.