Old habits fade slowly. When I was working, I was typically up and out of bed by 05:30. Now, after nearly 10 years of retirement, sleeping in has stretched to about 07:00. Since my early morning tendencies left me with and hour and a half before my scheduled ‘day before departure Covid-19 test’, I started with a brisk walk hoping for some exercise and an opportunity to take some Prague photos without people – or at least with as few people in them as possible. Our walk through the Jewish Quarter (again led by Jana) was scheduled for later in the morning so I had ample time to indulge in a big breakfast, too.

First, take a powder.

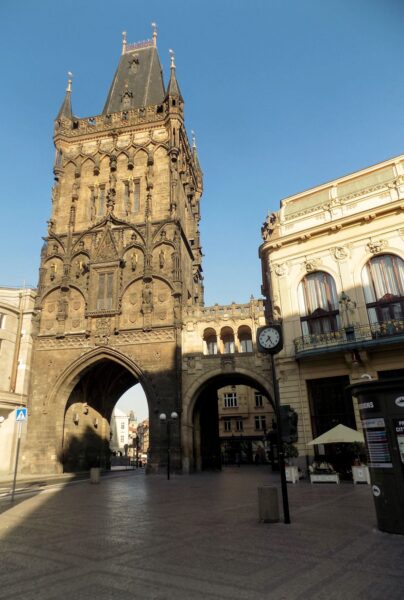

While I intended to take pictures of anything that caught my eye, I also had a number of specific photos in mind including trying to get a better picture of the Hus Monument in Old Town Square (which I finally did after several attempts), another of Prague’s odd museums – the Museum of Torture, and the Powder Tower – one of the old city gates that not only had a memorable appearance

but had served as a directional marker for me. (Since I often walk alone, I usually try to find a structure that stands out from its surroundings to use as a point of recognition knowing I can always find my way back from there.)

Construction on the 65-meter-tall tower, which was one of the Old Town’s 13 original city gates, began in 1475 when King Vladislav Jagellonský (Vladislaus II) laid the cornerstone. Its Late Gothic architecture mirrored that of the Staroměstská mostecká věž or Old Town Bridge Tower that stood near the Charles Bridge.

This resemblance likely provided the original appellation of New Tower. Its more common name arose from the the decision in the 17th century to use the tower to store gunpowder. The façade was adorned with sculptures resembling the work of Peter Parler prominently seen on the Charles Bridge. The sculptures on the tower were replaced in 1876 more than a century after the tower itself had suffered severe damage in the Battle of Prague during the third Silesian War.

Josefov or the Jewish Quarter – a brief history.

Prague’s Jewish Quarter was born in 1437 when King Albert, the first Habsburg monarch, ascended to the throne and, as one of his first acts, established the area where the city’s Jewish citizen’s would now have to live.

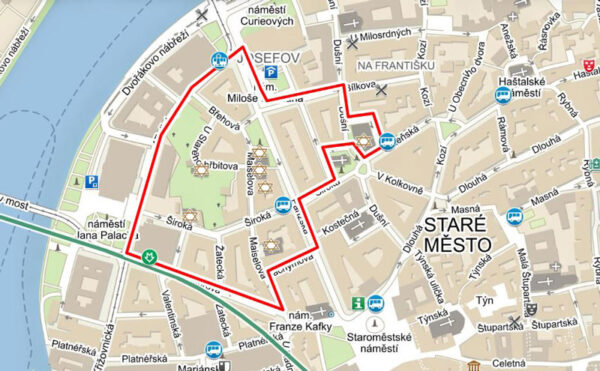

[Map of the Jewish Quarter from livingprague.]

His designated area, just north of Old Town Sqa]re abutted the river and was, as was most of the land in that area, prone to regular flooding. It’s likely the Jews of Prague had likely been segregated there for some time before Albert’s decree. (Although the designation isn’t properly used until the 19th century, I will use Josefov interchangeably with Jewish Quarter. I’ll also be using images somewhat randomly to break a wall of text.)

This isn’t to imply that life for the Jewish population of Prague was easy before the Quarter was officially established. The city’s Jews were the victims of a pogrom as early as 1096.

By the middle of the twelfth century the area along Široká Street had become the center of Jewish life. However, under the influence of the Crusades and church edicts during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, the Jews of Prague saw a continual degradation of their status.

Then, in 1254 and 1262 King Přemysl Otakar II issued a pair of edicts establishing new Jewish privileges. They made the Jews “servants of the King,” prohibited violence, protected their festivals, and barred damaging cemeteries and synagogues. Jews were granted religious freedom and were allowed to set up their own administration. As a form of protection (or confinement?), six main gates closed off access to the Jewish quarter.

(The Old-New Synagogue built ca 1270).

It helped. But not for long. On Easter Sunday 1389, a new pogrom saw an estimated 1,500 Jews killed. The Jews also didn’t help themselves in the early 15th century when they supported the Hussites in the wars from 1419-1434. The resulting power shift opened some doors for the Jewish population while closing others. They lost their banking monopoly but were able to become more involved in commerce and crafts. This didn’t sit well with established burghers and craftsmen and they began demanding Jews be expelled from the city first in 1501, again in 1507, and yet again in 1517.

It wasn’t until the period between 1543 and 1545 after the Jewish population had reached about 1,200 that Ferdinand the First acceded to the burghers demands.

The expulsion didn’t last very long. In 1567, Emperor Maxmilian II reconfirmed Jewish privileges and issued an imperial charter easing restrictions on Jewish trade and business. His successor Rudolf II did more than reaffirm Jewish privileges. He expanded them. First, he confirmed the affiliation of Jews to the imperial court. Then, in 1599 he exempted the Jewish community from all customs and toll duties in Prague (but not high taxes). It was in this period, something of a Golden Age for Czech Jews, that Mordecai Maisel was not only the mayor of the Quarter but rose to the position of Finance Minister in Rudolf’s court. Today, the 1592 Maisel synagogue

still stands on Maiselova – the street that bears his name and that was the first stop on our tour.

Advance and retreat continues.

By 1680, the Jewish population of Prague had grown large enough that Emperor Leopold the First was considering stricter segregation measures but an outbreak of plague that killed 3,500 solved the problem for him. The population quickly recovered and by the last years of the century exceeded 11,000. Hoping to slow this growth, Emperor Charles VI issued the Familiants Law that allowed only the eldest son in each family to marry. He also oversaw the first truly detailed census in 1729. It counted 10,507 adults in Josefov.

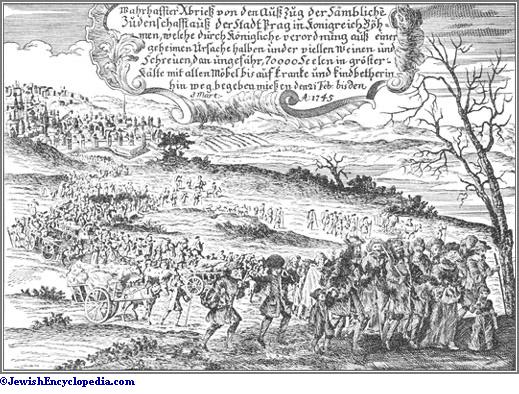

The Jews were expelled again in December 1744 under an order from Empress Maria Theresia and were allowed to return in 1748 only after agreeing to pay a Tolerance Tax of 20,000 gulden per year for five years.

[Painting of Maria Theresia – Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain.]

(One source I found reports that they paid a one time 204,000 gulden Tolerance Tax as well but I couldn’t find independent verification.)

Josef II.

In 1780 Josef II succeeded Maria Theresia and began what essentially became a second Golden Age for Jews in Prague. When he wasn’t commissioning operas by Mozart, Josef began a set of reforms in 1781 beginning with removing the obligation for Jews to wear special clothing. Next, he reopened paths for Jewish participation in trade, crafts, and agriculture, and he provided them access to all local schools.

In part, this was a systematic policy of Germanization in which Jews had to adopt German family names and all business transactions had to be undertaken in that language. In 1784, Jews were brought under the purview of the public judiciary, and Jewish courts were restricted to deciding cases solely involving religious and family law.

[Painting of Josef II – Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain.]

The situation continued to improve over the ensuing decades. The first Austrian constitution abolished the Familiants Law, freed the Jews from being required to live in segregated areas, and set them on the path to full equal rights. The year 1850 saw the formal incorporation of the Jewish Quarter as part of the city of Prague and it was at this time that the district chose the name Josefov (or what the mainly German speaking Jews would have called Josefstadt) to honor Josef II. That decade also saw Jews granted the right to own property and land and they became fully emancipated under the 1867 constitution.

The Jewish population of Prague grew to become one of the largest in Europe – exceeding 20,000 by 1889 – but while many remained in Josefov, others who could afford to do so relocated to more pleasant areas of the city. As these more prosperous Jews left, the quarter, known for frequent flooding and tightly crammed buildings, began to deteriorate just as the city itself was beginning to expand.

In the latter half of the 19th century, Prague’s city planners razed nearly all of the former defensive walls to allow the city to both expand and unify. This time period began a new era of city planning all over Europe and Prague was no different.

By the end of the 19th century, modernization was all the rage and some of the improvements the city planned to implement included reorienting the roads, expanding the electric network for better lighting and expanded public transportation, and establishing systems to supply potable water and remove sewage. Over nearly five decades they gathered city-wide statistics broken down by neighborhood on housing overcrowding, overall hygiene, and mortality rates. Given its inherent disadvantages, Josefov didn’t fare well in any of these metrics. We’ll take a look at what happened in the next post.