The good news was that of the three nights our group was in Prague the tour included concerts on two of them. Even better, tonight’s concert was at one of Prague’s most famous music venues – the Rudolfinum. Less than good news was that this first concert – the Final of the Clarinet competition of the Prague Spring International Music Competition – started at 18:00. With no bus, this meant Shlomit had to coordinate two cabs and potentially two separate return times because, at 1.5 km from the hotel, it was a bit farther than anyone wanted to walk especially dressed in our better clothes. Also, because the program required each of the three finalists to play the same two pieces of music and I was utterly unfamiliar with either composition, I anticipated an evening that had the potential to range from rapturous to disastrous.

A little history

The Rudolfinum began its life when it opened in 1885 as a center for musical and fine arts. The project itself began as a gift from the Böhmische Sparkasse (Czech Savings Bank) to celebrate its 50th anniversary. The bank, under the urging of its then director Wenzel Worowka, approved 400,000 guldens in 1872 for the construction of a House of Artists. In 1873, the bank’s board conferred the name Rudolfinum ostensibly to honor Rudolf I, the Crown Prince of Austria and Prince Royal of Hungary and Bohemia.

(Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain)

At the same time, by expressing the bank’s loyalty to the ruling Habsburgs, it was probably good for business.

Excavations began in June 1876 but proximity to the Vltava River required laying the building’s foundation deeper than originally planned and actual construction couldn’t begin until 1878. Masonry work for the first floor was completed in 1880 and by the end of 1882, work on the interior was nearing completion. When it opened, the building looked like this.

(From rudolfinum.cz / Prague City Archive)

Today, the building that stands on Jan Palach Square, looks much the same.

(Wikimedia Commons – By che – Own work, CC BY-SA 2.5)

The northern façade of the building – the area hosting the art gallery – is decorated similarly to create a unified appearance.

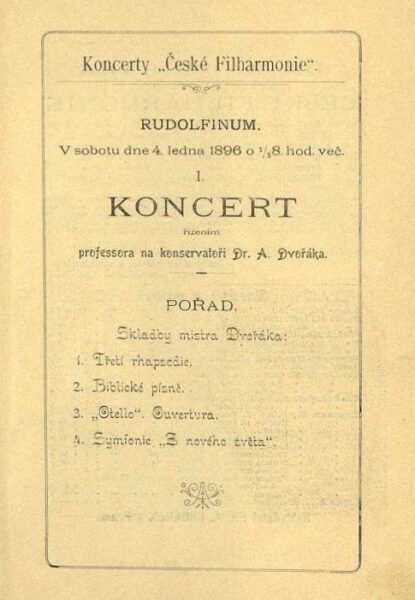

In its early days, the Concert Hall mainly hosted performances by the National Theater Orchestra and the conservatory orchestra. The Czech Philharmonic Orchestra had its debut at the Rudolfinum on 4 January 1896 with Antonín Dvořák conducting the Slavonic Rhapsody No.3 in A flat major, the world premiere of Biblical Songs Nos. 1-5, the Othello overture, and his 9th Symphony – From the New World.

(From rudolfinum.cz)

And then the sound of silence

Artistic silence descended on the Rudolfinum during the First World War when the building became an infirmary for wounded soldiers. One would have hoped that the end of the war would have seen the return of performances but such was not to be the case. The collapse of the Habsburg empire allowed the formation of the new Republic of Czechoslovakia. The new country’s leadership then selected the Rudolfinum as the ideal location to seat the Chamber of Deputies of the National Assembly and it continued in that role until 1939.

Led by Neville Chamberlain, the UK, France, and Italy signed the Munich Agreement in September 1938 hoping that ceding the Sudetenland to Germany would appease Hitler’s ambitions. It didn’t and by 1939, the territory looked more like this:

(From USHMM CC BY-SA 3.0)

Enter the Butcher of Prague

From the perspective of just about anyone other than Nazis or Nazi supporters, Reinhard Heydrich was vicious, sadistic, and downright evil. Soon after the portion of the former Czechoslovakia became the German Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, Heydrich, though he was only 37 at the time, was installed as the Deputy Protector and he went right to work terrorizing the populace. He immediately declared martial law and within six days had ordered 142 executions. Of course, this should come as no surprise to anyone who is familiar with his history and rise through the power structure of the Third Reich.

In 1938, Heydrich not only abetted but helped coordinate the events of Kristallnacht. He didn’t simply grant permission for arson and the destruction of Jewish businesses and synagogues, he coordinated the pogrom with the SS, SD, Gestapo, uniformed police (Orpo), SA, Nazi party officials, and fire departments. Many historians cite this event as the beginning of the Holocaust.

Heydrich was one of the three organizers of Operation Himmler – a false flag operation that provided the pretext for Germany’s invasion of Poland.

(So effective was Operation Himmler and the propaganda machine built by Joseph Goebbels, that on 1 September 1939, America’s paper of record, the New York Times, under the headline “Hitler Gives Word” reported that Germany had been attacked by Polish saboteurs according to “Chancellor Hitler.” Its principal source for the report, including the assertion that the attack had been a signal for ‘”a general attack by Polish frantireurs on German territory ‘”, was the Nazi Party newspaper Volkischer Beobachter.)

(Wikimedia Commons By Deutsches Bundesarchiv)

And on 10 October 1941, less than two weeks after his appointment to Prague, he was the senior officer at a “Final Solution” meeting of the Reich Security Main Office in Prague that discussed deporting 50,000 Jews from the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia to ghettos in Minsk and Riga.

His reprisals against any resistance were so brutal the Czechs called them Heydrichiáda and he became known as the Butcher of Prague. (In an act of great hubris, Heydrich typically rode in a car with an open roof. In perhaps another act of hubris, when the sten gun of Josef Gabčík, one of two Czech resistance fighters assigned to assassinate him, failed, rather than leaving the scene, Heydrich ordered his driver to give chase providing the other Czech, Jan Kubiš the chance to throw a modified anti-tank mine at his car. Heydrich died of his wounds in a hospital eight days later on 4 June 1942.)

So what has Heydrich to do with the Rudolfinum? The Deputy Protector considered himself a cultured man and during his time in Prague ordered the restoration of the theater. He engaged the architects Antonín Engel and Bohumír Kozák to not only restore the original function and decoration of the concert-stage and auditorium but also tried to improve the hall’s acoustics an aspect that had been considered subpar since the building’s opening. Only the Prague German Philharmonic Orchestra performed there (likely part of Heydrich’s goal to ‘Germanize the Czech vermin’ as he’d once told his subordinates. Today, the Dvorak Hall, the main concert venue of the Rudolfinum, is considered among the finest acoustic halls in Europe. And that is probably the only grain of gratitude the citizens of Prague owe Reinhard Heydrich.

The Competition

Though more figurative than literal, it had the potential to be a long night of music so the show got started early at 18:00. As I noted above, three clarinetists were scheduled to perform the same two works – the Première rhapsodie by Claude Debussy and Rudolf Kubin’s Concerto for clarinet and orchestra. Together, the two compositions need half an hour more or less. Thus the performances should total an hour and a half with a pair of intermissions and, of course the award to the winner. That meant it wouldn’t necessarily be an overly long evening but, to me, it projected as one potentially lengthened by repetition.

The hall was beautiful

and the acoustics lived up to their billing. I found the music less than enchanting and, I think others in our group concurred. Five of us had Shlomit call a cab after the second performance. Hearing both pieces twice combined with a growing ‘hanger’ because I’d eaten such a light and quick dinner, prompted my early departure.

As for the performers themselves, I saw the Frenchman, Lilian Lefebvre, who ultimately won the top prize and a Chinese woman, Yung-Yuan Chiang, who took third. I didn’t see the second place finisher, Anna Sysova, who was the hometown favorite. As for the pair I did see, I liked Lefebvre’s performance of the Debussy but much preferred Chiang’s interpretation of the Kubin.

I have to add that a pre-concert talk (that my wandering might have caused me to miss) would have been very helpful given the general unfamiliarity of both compositions but particularly so the Kubin. The two performers approached the piece very differently with Lefebvre taking a very aggressive attack and Chiang a softer more rounded approach. Based on the reaction in the hall, I had the impression that the audience agreed with me but the orchestra agreed with the ultimate decision by the judges. Because I didn’t know the music at all, I don’t know whether the judges rewarded originality or conventionality.

If you’re curious, here are Lefebvre’s winning performances from that night.

and

In the next post, I’ll begin recounting my last day in Prague that featured an early morning walk on my own, a guided tour of Josefov (aka the Jewish Quarter) with Jana, a chance to stand where Mozart once stood, a final concert, and more.

A good to great read there Todd.

I was entertained by the history provided- thanks.

Thanks for reading & commenting, Shell. New information you can use to entertain your friends and maybe snakes!