Having taken a brief but, I think necessary, introductory detour into trying to understand the unique world view of Australia’s First People we can return to the main road of my personal journey as one among 20 Road Scholars. Sometime around 07:30, the IP reached Adelaide. We disembarked, rounded up our luggage, and boarded the bus for our “coach tour of Mount Lofty.” We set out for a ride of about half an hour from the Railway Station (I had a ticket just for one) headed for the highest peak in the Mount Lofty Ranges – called Yuridla by the Kaurna people but generally known as Mount Lofty – climbing the Mount Lofty Summit Road until we’d crest at the majestic height of 710 meters above sea level. (We traveled from point A to point B in the map from Bing Maps below. In the lower left you’ll also see Kangaroo Island where, after a night in Adelaide, we’ll spend the ensuing two nights.)

I would like to acknowledge the Kaurna People – the Traditional Custodians of this land. I would also like to pay respect to the Elders past, present, and emerging and extend that respect to other Aboriginal people present.

Along the way, S, our local site coordinator, provided a little information about the history of Adelaide (named after Queen Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen – the wife of William IV of England) and the importance of Mount Lofty.

Matthew Flinders named the peak on his mapping expedition when he spotted it on 23 March 1802 from Kangaroo Head on Kangaroo Island. Hence, Flinders is memorialized

at its summit. A moment of greater importance to the city of Adelaide, occurred nearly a quarter century later when Colonel William Light is believed to have chosen the site where the city would be built while viewing the Adelaide Plains from hills near Waterfall Gully in 1836. Adelaide was to be a planned city and Light, who was the first Surveyor-General of South Australia, was largely responsible for that planning. Although it might require a bit of imagination to erase the modern city from the image, this view

should provide some indication of the potential White saw in the plain below the peak.

Hindmarsh v Light

As we stood making our own survey of Adelaide and peeking excitedly at a nearby koala,

S spoke for the first time (but certainly not the last) of the dispute between Colonel Light and John Hindmarsh – the colony’s first governor.

Hindmarsh, who had served as a Rear-Admiral in Horatio Nelson’s navy, favored coastal locations such as Port Lincoln, Port Adelaide, Victor Harbor, and Rapid Bay but Light chose the Adelaide Plains site because of its good water supply, fertile soil, and proximity to the Adelaide Hills, which he believed would provide higher rainfall. This last factor was important given South Australia’s status as the continent’s driest state. (Most of Adelaide’s average of 546 mm of rain falls in the summer. It’s the driest capital city in Australia.)

Light effectively decided on the site for the planned capital city on 18 December 1836. Hindmarsh arrived ten days later and the dispute between the two men began almost immediately. Light couldn’t begin his formal survey of the plain and develop his plans for the city’s layout until Hindmarsh

[From Wikipedia – Portrait of John Hindmarsh – Public Domain]

approved. The dispute culminated in a public vote on 10 February 1837 ending with Light’s plan winning by a vote of 218-137. Despite losing the vote, the autocratic, abstemious, and unpopular Hindmarsh continued attempting to undermine Light. Hindmarsh was recalled in July 1837.

Light’s Vision

(I’m watching the dust as it falls and settles on my fate.)

With regard to city planning, William Light was both a man of his time but in many ways a man ahead of his time. Although the plain might have lent itself to a grid design, Light’s use of this pattern in both South Adelaide (now the city center) and North Adelaide conformed with the patterns of British design in the empire’s colonies. However, most of the rest of his approach broke with convention.

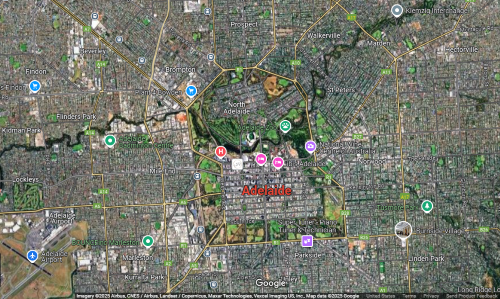

This break began with his method of surveying the city. His was the first known trigonometrical survey – a method far more precise than the standard running survey used in that time. His method likely aided his decision to position the city on gently rising ground straddling Karra Wirra Parri or as he would have called it the River Torrens. Light also introduced the concept of a “Garden City”. He surrounded Adelaide with a 903 hectare belt of parklands. (Although the rise isn’t visible in this Google Maps satellite image, you can clearly see the grid, the river, and the belt of parklands.)

It’s almost certain that Light’s plan for Adelaide provided significant inspiration for Ebenezer Howard’s 1898 book Garden Cities of To-Morrow which, in turn served as the genesis for the global Garden City Movement.

Somewhat sadly, a combination of tuberculosis and the battles with Hindmarsh took a toll on Colonel Light

[From Wikimedia – William Light – Public Domain]

and his poor health was among the reasons he resigned as Surveyor-General of South Australia on 21 June 1838. He died at age 53 on 6 October 1839.

City of Churches, City of Pubs

Established in 1836 using many of the principles espoused by Edward G Wakefield, himself a former convict, the colony of South Australia was the first free British settlement on the continent and Adelaide was built free of convict labor. Wakefield’s systematic colonization theory (which he also attempted to apply in New Zealand) espoused two main ideas. First, he advocated for the sale of “crown lands” to finance the immigration of laborers. His second goal was creating a balanced colonial society with a mix of laborers, tradespeople, artisans, and capitalists. These ideas influenced the text of the South Australian Act of 1834 also called the Foundation Act or South Australian Colonization Act.

[From Wikipedia – Public Domain]

Perhaps influenced by Wakefield’s emphasis on attracting migrants and people of mixed skills and professions, the city’s founders emphasized religious tolerance from the outset. They not only allowed but encouraged diverse religious groups to practice their various faiths freely. (Except, of course, for the Aboriginal People because, under the principle of terra nullius, they didn’t exist.) Early in the city’s life, 40 to 50 churches occupied space in the city’s central business district.

At first blush, it might seem odd that the City of Churches was also known as the City of Pubs. But understanding that the first cognomen’s use was describing Adelaide’s religious tolerance and that the city was something of Wakefield’s blend of “laborers, tradespeople, artisans, and capitalists” a diversity of pub life seems considerably more reasonable and a bit more natural.

By the time of Adelaide’s establishment in the mid 1830s, the public house was taking on the characteristics we associate with pubs today. They began to be purpose-built with distinctive facades and fittings specifically for retailing liquor and offered a wider range of alcoholic beverages than the taverns of the time. Perhaps most importantly, pubs became central to community life, hosting various social events such as christenings, holiday celebrations, weddings, and wakes. In other words, they were a full service establishment taking the community from birth to earth, if you will. They were accessible gathering places for the working class, where people could find community support.

Although the city proper has fewer than 50 pubs today, it’s reported to have had nearly 200 in the heyday of the pub. As with so many stops, RS had so filled our time in Adelaide that I found no opportunity to drink up (either a beer or the atmosphere) in even one such establishment.

There’s more to report about our day in Adelaide so in the next post, I’ll take you down from Mount Lofty and into the heart of the city.

Good stuff Todd. I knew of the city but not so much of its history.

200 pubs… u don’t say?

And I got to nary a one 😢

Well, I think we all got to the bar in the hotel, Todd, so there was that!

Well there was that! 🥴🤣