As always seems to be the case anything that happens in the Balkans has distinctive layers of complexity that all but demand deeper exploration than one might normally apply in describing similar circumstances elsewhere in the world. Costs are always prohibitive and facilities so often degrade into unused white elephants that people apply the term “ruin porn” to describe them. (A 2021 article on moneycontrol.com noted, “Every Olympics held since 1960 has overshot its budget by an average of 172 percent, which is the highest overrun recorded for any mega event – not just sports.”) Somehow, it seems predictable and strangely fitting that the ruin porn of the remnants of the Sarajevo Games would stand apart from so many others.

But first…

As I noted in the previous post, Sarajevo wasn’t the obvious choice to host the Olympics – even in Yugoslavia. Before its transformation spearheaded by Branko Mikulić, the head of the Communist Party in Bosnia, Sarajevo was a city bereft of infrastructure but saturated with pollution both in the air from the coal fired utilities and in the Miljacka River. Bolstered by American television money, Mikulić created a Sarajevo very different from the one that Debbie Armstrong had visited just a year earlier during the Alpine World Cup.

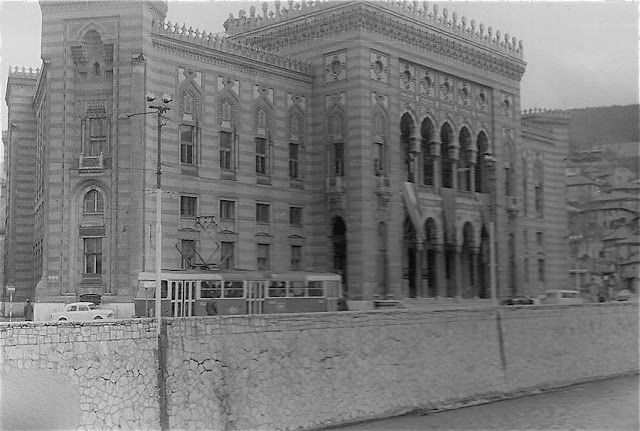

[Photo From Twitter @BosnianHistory.]

The United States won a total of eight medals in Sarajevo in 1984. Four were gold and four were silver. Athletes born or raised in the state of Washington accounted for half those totals – three in Alpine skiing and one in figure skating so it’s somewhat unsurprising that a Spokane newspaper – The Spokesman – would publish a retrospective 30 years after the Games ended. In it, Phil Mahre, Debbie Armstrong, and the lone Yugoslav medalist Jure Franko shared some of their memories.

When she arrived for the 1984 Games, Armstrong recalled for the Spokesman, “…we show up in ’84 and it was so evident that this city was ready. I felt like it was a coming-out party for Yugoslavia and Sarajevo.”

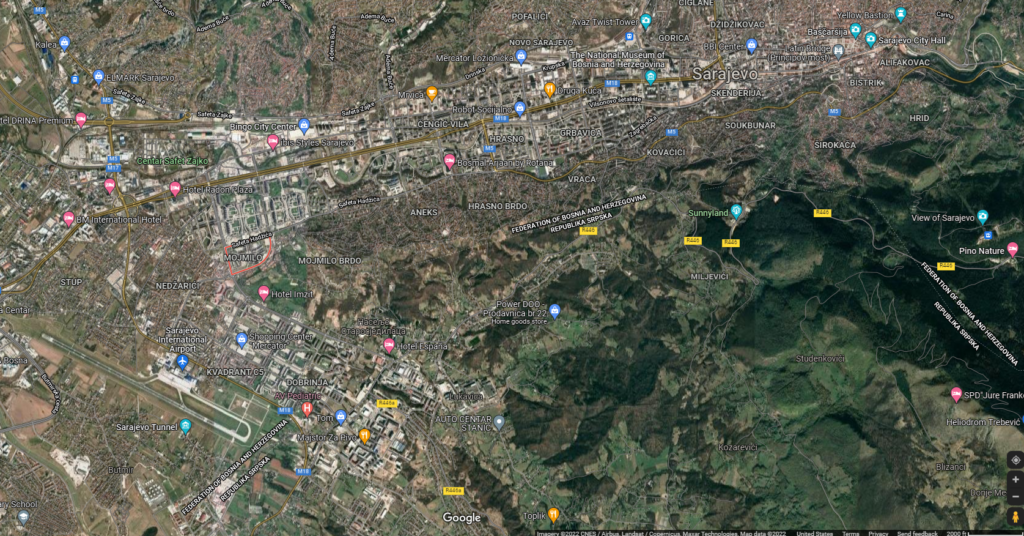

The Main Olympic Village in the Mojmilo District was a bit more than seven kilometers from the Old Town. (There was a secondary Village for athletes and coaches of cross-country skiing, Nordic combined, and biathlon on Mount Igman.)

[Satellite photo from Google Maps.]

Phil Mahre, who competed at both the Innsbruck and Lake Placid Games, calls the Sarajevo Games his most memorable for reasons quite beyond winning a gold medal. He told the Spokesman, “I met a lot more people and took in the experience. I took a week away from skiing and just played volleyball and basketball and hung out at the Village. They were probably the most colorful games I went to.”

Armstrong recalled, “It was Disneyland for athletes inside that Olympic Village. It was fabulous.”

Reflecting on how disconnected Olympics feel in big cities like Salt Lake City and Vancouver, B C, Mahre added, “It was just a completely different atmosphere. It was a small community. There will probably never be another Games like that. Those games were special.”

But the Bosnian people left a lasting impression for Armstrong. An elevator attendant gave her a good luck charm shortly before she won her giant slalom gold medal. “It was a little thing that I was able to attach to my ski team parka. And it’s still attached to that parka today,” she told the Spokesman in 2014.

When local hero Jure Franko won his silver medal, he had to fend off kisses from men and women alike. “The place just went nuts,” he told the Spokesman in 2014. “It really brought the whole country together.”

It was, as Peter Korchnak of the blog Remembering Yugoslavia called it, “the high point of Yugoslav history, Yugoslav sports history.”

And then…

Marshal Josip Broz Tito was dead. There is no doubt whatever about that. This must be distinctly understood for anything to come of the story I am about to relate.

[Photo from Wikimedia Commons – Public domain.]

Tito had more or less unilaterally ruled Yugoslavia from 1953 until his death in 1980. Like Sarajevo, Tito was a study in contrasts. In some ways he was ruthless and repressive while in others he was far more lenient than many of his communist counterparts of the era. When he died with no clear succession plan in place, Yugoslavia’s breakup was all but inevitable. Although all were, in some ways, southern Slavs, Yugoslavia was a nation of ethnically and religiously diverse people cobbled together for political convenience and held together by the force of personality and iron rule of Marshal Tito.

Tito had borrowed prodigiously to prop up Yugoslavia’s economy and even by the mid 80s the country was sagging under the weight of that debt. Though the fraying rope tethering the republics together would hold until 1991, it was at least a peripheral miracle that there was no evidence of the tensions building between the republics during the 1984 Olympics.

The first fighting broke out the day after Slovenia formally seceded from Yugoslavia on 25 June 1991 when the Yugoslav People’s Army (JNA) began a series of limited skirmishes around Slovenia. However, even as the situation grew hotter, Sarajevo, in fact most of Bosnia and Herzegovina, took pride in its multiethnic, multicultural, peaceful coexistence. Even during my visit, on a walk through the Baščaršija spotting

women in hijabs and burkas strolling past others in miniskirts while men sat by in cafés eating bureks, drinking strong Bosnian coffee, and ubiquitously puffing away on a cigarette was a common sight.

However, once Slovenia made the first move and Croatia followed soon thereafter, the end of Yugoslavia was imminent and, just more than nine months later, the JNA, aided by Bosnian-Serb paramilitary forces began the Siege of Sarajevo on 5 April 1992.

Occupying much of the high ground, the JNA used Olympic venues such as the Bobsleigh track as artillery launch points.

[Photo from Business Insider By Dado Ruvic/Reuter)].

Some venues such as Zetra Hall, where Torvill and Dean scored their perfect 10s and Scott Hamilton captured his Olympic gold medal, were flattened. The Zetra Ice Rink where Dan Jansen and Bonnie Blair made their Olympic debuts became a makeshift vegetable garden and Koševo City Stadium (which has since been rebuilt), because there was no other place to bury victims of the siege and because the wood from the seats could be used to construct coffins, became a makeshift morgue and cemetery.

[Photo from Business Insider By Dado Ruvic/Reuters.]

So many of Sarajevo’s venues had become not simply ruin porn but war ravaged ruin porn.

Although I’ve written about my fondness for visiting cemeteries, after my interaction with the people of Sarajevo, this was one cemetery I couldn’t bring myself to visit.

[Photo from The Spokesman.]