Oy! Just oy!

One reason I have a geological addendum for each location on this Olympic host cities tour (aside from the China pun, of course) is my general interest in the forces that have shaped our planet. Another is that I believe the geology, geography, climate, and topography of a location play a substantial role in governing human interaction with a place. Calling my formal geological education limited is a massive understatement but I’m able to read and patiently investigate until I’ve convinced myself that I have enough understanding to communicate the information to readers in an informal way using as little jargon as possible but also going beyond what a reader might find on Wikipedia. So, when I begin research on a location’s geology and one of the first sources I find opens with this sentence,

The geodynamic evolution of the Dinaride Mountains of southeastern Europe is relatively poorly understood, especially in comparison with the neighboring Alps and Carpathians.

or I have to wade through a description like this

The present-day configuration of tectonic units suggests that a former connection between ophiolitic units in West Carpathians and Dinarides was disrupted by substantial Miocene-age dislocations along the Mid-Hungarian Fault Zone, hiding a former lateral change in subduction polarity between West Carpathians and Dinarides.

my reaction is summed up by this section’s header.

A Serbian coin and the middle of the month

(Wikimedia Commons Derivative Work GabrielZafra BY CC-SA-3.0)

Even though it’s in French, the map above should give you some idea that Bosnia and Herzegovina (B&H) is dense with mountains. These mountains are often called the Dinaric Alps but most geologists use the name Dinarides derived from Mount Dinara a peak on the border with the Dalmatian part of Croatia and B&H. Four of the five mountains that surround the valley where Sarajevo lies, including all of the Olympic Mountains – Bjelašnica, Igman, Jahorina, and Trebević – are part of the Dinarides. (Curiously, the tallest of Sarajevo’s mountains, Mount Treskavica at 2,088 meters {6,850 feet} played no part in the Olympics.)

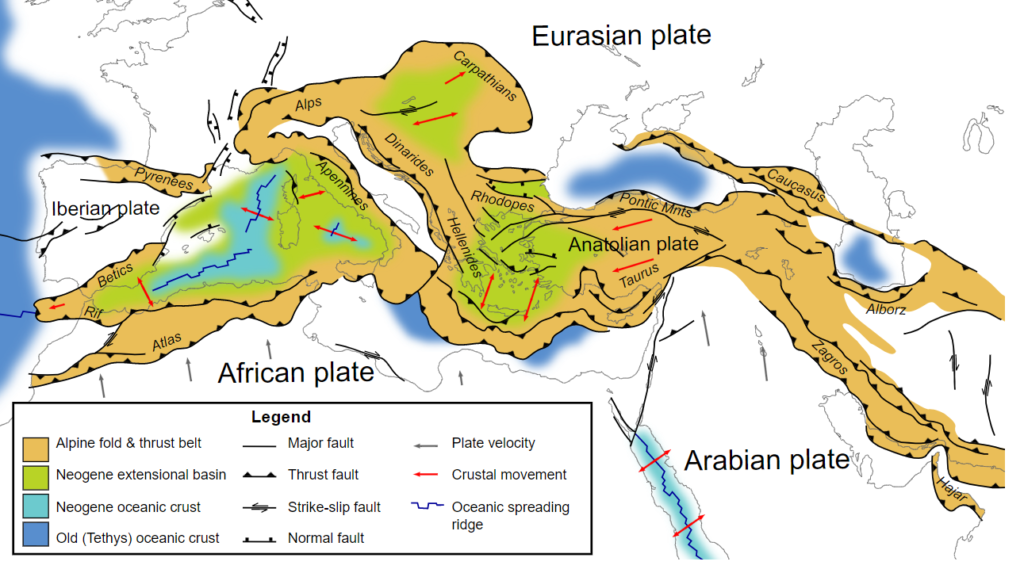

The Dinarides are part of the Alpine-Himalayan orogenic belt that stretches along the southern segment of the Eurasian Plate for more than 15,000 kilometers (9,300 miles). Spanning the late Mesozoic and early Cenozoic Eras, the Alpine orogenesis is the youngest of the three main orogenies that shaped the European continent as we know it.

(Wikimedia Commons – By Woudloper – Own work, CC BY-SA 1.0)

Although the oldest rocks in the region date to the Jurassic (about 200MYA) beginning about 110 million years ago and continuing for a period of 60-65 million years, the African, Indian (not shown above), and Arabian plates moved north while the Eurasian plate slid southward. As they collided and converged they created a subduction zone (where one plate slides underneath another) that built a number of mountain ranges as you can see on the map above. A smaller plate called the Adriatic plate was also involved in the labor that gave birth to the Dinarides. That gestation culminated near the end of the Alpine orogeny and they are a fold-thrust mountain range .

Karst be he who moves my stones

In terms of their composition, the Dinarides are substantially different from many of the mountains I’ve visited and described both throughout this series and the totality of this blog. The Dinarides rocks are primarily limestone and dolomite deposited on top of a huge carbonate platform. Carbonates (salts of carbonic acid) are a product of one of three types of precipitation – abiotic, biotically induced, or biotically controlled – rather than being a sediment transported from elsewhere and a carbonate platform. The fact that they’re precipitated salts indicates that the area was once covered by seas and lakes. In other word, the Dinarides are essentially karst mountains that look like this.

(From outdooractive.com)

(If you’re interested in further exploration of karsts, the term has appeared elsewhere in this blog and I wrote rather extensively about the Karst plateau that is the primary geographic feature of the region in the post called Feeling sLOVEenia.)

Curiously absent

While there is considerable evidence for substantial glaciation throughout the Balkan peninsula, most of it is farther south such as at Jablanica Mountain near the border between Albania and North Macedonia or at such coastal mountains as Velebit in Croatia. There’s considerably less evidence of glaciation in central B&H. This is something of a surprise since Sarajevo sits in a valley circled by five main mountains.

The best current explanation for the lack of glaciation is that the ice caps and the large ice-fields along the coastal ranges prevented humid air masses from penetrating inland. The resulting significantly drier conditions in the Balkan interior and in the Pannonian Basin compared to the coastal margin of the Balkan Peninsula that then inhibited the accumulation of enough snow to generate glacier formation.

Finding a city like Sarajevo in a valley isn’t particularly surprising since valleys are among the most common landforms on the Earth. Erosion is the main process involved in forming valleys with wind and water among the principal erosive forces involved. Whatever forces are most present will be a main factor in determining a valley’s shape.

The three common types of valleys are V-shaped valleys, U-shaped valleys, and flat-floored valleys each with its own distinctive shape and the shape is dependent on three main factors: the forces driving the erosion (as mentioned above), the composition of the rock or soil being eroded, and the length of time the forces of erosion have had to impose their will on the land.

A V-shaped valley is a narrow valley with steeply sloped sides formed by strong streams that, with enough time, cut down into the rock through a process called downcutting. While the Grand Canyon in the U.S. is a V-shaped valley, this

(Wikimedia Commons BY -Yasuhiro-Kojima-CC-BY-SA-4.0)

look at Mount Kistanistavi provides an easy visualization.

A U-shaped valley (sometimes called a glacial trough) is a valley characterized by steep sides that curve in at the base of the valley wall with broad, flat valley floors. They are found in areas with a high elevation and in high latitudes, where the most glaciation has occurred. They’re formed by glacial erosion as massive mountain glaciers moved slowly down mountain slopes. Had I been able to crest the Going to the Sun Road on my visit to Glacier National Park, I might have had a photo like this one of a U-shaped valley.

(From FLICKR BY User Ken Lund)

The flat floored valley is the most common type in the world. Like V-shaped valleys they are formed by streams, but they are considered mature while V-shaped valleys are considered more “youthful.” Given enough time, the slope of a stream’s channel becomes smooth and as it begins to exit the valley, the floor gets wider. Because the stream gradient is low, the river begins to erode the bank of its channel instead of valley walls eventually leading to a meandering stream across a valley floor.

Sarajevo’s valley

(Wikimedia Commons BY-Julian-Nyca-CC-BY-SA-3.0)

is largely the work of the Miljacka River.

Next up, some early humans.