Today you get to ride with me through the armpit and then to the toe fungus of Wyoming. The prospect doesn’t excite you? Let me explain. Since I was the only visitor at my first stop this morning, I had time to have a long chat with Sandy (not her real name) – the Wyoming Parks ranger there. We got onto the subject of my day’s itinerary and she provided that bodily disparaging description of my route because, I think, like the eastern plains of Montana. This isn’t the scenery people come to Wyoming to see. Still, I hope you’ll find some of the stops I made along the way both interesting and curious.

Douglas, Wyoming POW Camp

By the time the United States entered World War II on 7 December 1941, the war in Europe had been raging for more than two years and prisoner of war (POW) camps in Great Britain had become overcrowded. Even though only 2,000 or so POWs reached U.S. shores in 1942, with British camps already overcrowded the U.S. military knew it had to devise an American internment plan. During the course of the war, the two countries would hold a collective total of nearly 1,000,000 POWs.

The earliest steps the United States took to deal with the burgeoning POW problem included reactivating and re-purposing previously abandoned Civilian Conservation Corps camps (as we saw in Salina, Utah), opening unused portions of several major military bases, and setting up “tent cities” in remote areas of the country. Some of these tent cities would become more permanent camps as part of a $50,000,000 construction program. Other camps had to be outside a 150-mile-wide zone along the Canadian and Mexican borders and at least 170 miles from any coastal areas. They also had to be located a “safe” distance from shipyards, munitions plants, and other vital wartime industries to prevent possible sabotage. Although location was a factor in the construction costs, more of the expense resulted from the military’s insistence that to adhere to the terms of the Geneva Convention, the camps had to be constructed to the minimum standards of a regular military compound.

Sensing a possible economic benefit, many communities offered to host POW camps and had their local chambers of commerce lobby on their behalf. Located approximately 129 miles north of Cheyenne, the town of Douglas not only met the broad requirements but also the specifications the Army set for the ideal camp:

- 350 acres of level and well drained land (Douglas had 687 acres above the North Platte River

- Within 5 miles of a railroad (Douglas’ land was within 1 mile)

- At least 500 feet from any public road (The Douglas site was undeveloped)

After a brief legal battle, the federal government acquired the land and announced the construction of the camp in January 1943. Peter Kiewit and Sons from Omaha, Nebraska came in with the low bid and the company set up operations in Douglas by February. Four to five hundred construction workers used the 4-H buildings on the state fairgrounds as dorms and a dining hall. The government contract specified the buildings be completed within 120 days; Kiewit and Sons finished the job in 95 days.

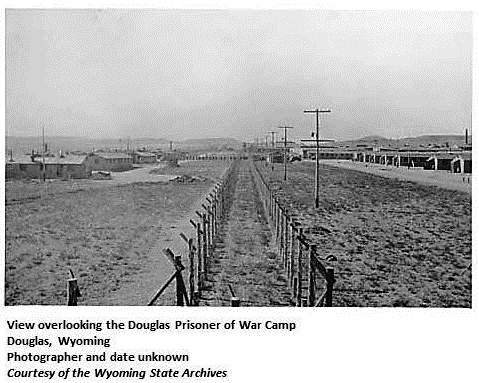

The inner fence was electrified. If the buildings on the left in the photo were part of the camp, they would be the Officers’ quarters and clubhouse which were the only buildings outside the camp’s perimeter. Inside, the prison complex was organized into three compounds, separated by wire electrified fencing, and each with a capacity of approximately one thousand men.

A group of 412 Italians were the first to arrive at Camp Douglas in August 1942. Captured in the Tunisian Campaign, they’d been transported by boat from Europe and then by train from New York City. By the end of 1942, the camp housed more than 1,900 prisoners all of whom were Italian.

As thousands of Wyoming’s men enlisted in the Army, the state lost much of its agricultural manpower. As they would elsewhere throughout the country, POWs would provide the labor in many essential agriculture related tasks particularly in harvesting crops whether it was cotton in the south or sugar beets and timber in Wyoming. Depending on the job, the POWs in Wyoming could be paid as much as four dollars per day.

Although the Italians surrendered on 3 September 1943, most of the prisoners weren’t released until the spring of 1944. The camp was largely abandoned from that time until October of that year when it saw an influx of Germans. From 1944-1946, the camp housed more than 3,000 German POWs. Like the Italian prisoners before them, the German POWs also provided thousands of hours in agricultural labor for which they, too, were paid daily wages of $4.00. It’s said that the thriftiest of the prisoners returned home with as much as $500.

The camp officially closed on 1 February 1946. Excepting the Officers’ Club, the site was gradually dismantled and much of the camp fell into disrepair. In that one remaining building, three Italian prisoners left a considerable artistic legacy in the 16 murals they painted more than 70 years ago.

Hoping to keep some remnant of the camp alive, the Douglas Lodge #15, Independent Order of Odd Fellows purchased the building from the Junior Chamber of Commerce in 1963. The efforts of the Odd Fellows have managed to keep the building preserved (though not completely restored) and it’s managed today by Wyoming Parks.

This video plays continuously at the site and you can see more photos here.

On the way to Laramie

Dome on the range

After my nice chat with ‘Sandy’, I returned to I-25 and continued south toward Cheyenne where I’d meet I-80 and turn west toward Laramie, my end point for the day. Once I made that turn to the west, I’d make a few stops along the way and I came upon the first of those about 15 minutes after I turned onto I-80.

This particular curiosity sits in a field just south of the eastbound lanes near exit 342. It would be easy enough to miss for travelers coming from the west and had I not known about it in advance of my arrival, I would certainly have missed it traveling to the west.

This is the cupola that sat atop the Wyoming State Capitol building in 1917. It was replaced at some later date and was subsequently purchased and restored by a resident of Granite, WY (the unincorporated town abutting this exit). He then placed the dome in a field near the 1892 Old Granite School House which is considered another historical landmark. Both were surrounded by a fence and, at a glance, the schoolhouse looked to me as though it had gone to seed. For this reason and because I hadn’t stopped to see it, I have no photo of it.

As authentication, I did find this picture

from the Wyoming Historical Society showing the Capitol as it was when the cupola graced the building rather than gracing a field some 20 miles west of Cheyenne.

from the Wyoming Historical Society showing the Capitol as it was when the cupola graced the building rather than gracing a field some 20 miles west of Cheyenne.

Metaphorically hopping back onto I-80 West, I needed to drive only about nine miles to reach my next stop on my “Curiosities of Southern Wyoming Tour,” Phin Deli Town Buford once known simply as Buford. There are several reasons this town merited a stop on the curiosities tour.

First, the town is named for General John Buford. Buford’s main claim to notoriety is that while in command of a division on the first day of the battle at Gettysburg he had his troops set up defensive positions there on 30 June in anticipation of the Confederate Army’s arrival. His men held the position until reinforcements arrived. This massive three day battle, as noted in the brief biography of Custer, was the turning point of the American Civil War.

Now, it’s not overly unusual to name a town after a famous military hero. In this case however, Buford was born in Kentucky, attended and is buried in New York at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, and died – possibly of Typhus – in 1863 just a few months after Gettysburg. I could find no connection between this particular general and Wyoming.

While interesting, that alone wouldn’t make it worth a stop but I thought it a fact worth mentioning. The next entry reveals what attracted me to Buford.

Note: In keeping with my 2022-2023 reformation of the blog into shorter entries, backdated to maintain their sequence, any comments on this post might pertain to its new configuration. See the explanation in the post Conventions and Conversions.

Nice travelogue, Todd, you have been a genial guide to some pretty inconsequential sites. How else could we have known about them? My mind, ravenous to learn about the amusing and trivial, thanks you. It has been fed its morning snack. I am eager to hear about the controversies of Laramie. Or, will we hear your controversial descriptions about some otherwise tame stuff? In either event, I anticipate having my eyes opened and my heart racing. BTW. thanks for verifying the cupola. Nice touch. I am a cupola fan. I am thinking bout going out there and spiriting it away and placing it on my roof.

.

Is anything really inconsequential?

The trips (and my recounting of them) have to include some lighter moments, I think. As for the Laramie controversy, it could be dependent on your initial point of view.

I think the cupola would be a handsome addition to your roof.