One and the same.

Now that the planetary diversion is over, I’ll return to the walking tour. Our next stop is the Cathedral found in the Kaptol section which dates from 1094 and is the oldest part of the city. The Cathedral’s formal names are the Cathedral of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary and the Cathedral of Saint Stephen and Saint Ladislaus but the residents simply call it the Cathedral. In a previous post I mentioned King Ladislaus who moved the bishop’s seat from Sisak to Zagreb in 1094. The saint and the king are one and the same.

The first cathedral was destroyed by the Mongols in 1242. The bishop at the time rebuilt it in the middle of the 13th century and it stood for more than 600 years until 1880. In that year, the cathedral was damaged beyond repair not by invaders but by the earthquake I mentioned previously as well.

The cathedral’s restoration was led by Herman Bollé who had recently finished supervising the construction of the cathedral in Đakovo. Though he wasn’t Croatian by birth, Bollé settled in Zagreb where he became one of the country’s most influential architects. (Remember his name. It will appear again.)

The neo-gothic restoration added a second tower where the original cathedral had only one. The two spires, each 108 meters tall make the Zagreb Cathedral not only the tallest sacred building in the country but the tallest building in all of Croatia.

As you can see, the restoration is still not quite complete.

Tunneling through to the funicular.

Visiting Zagreb in August 2016 gave us a chance to pass through the city in a way that few visitors before us had been able to experience. The Grič tunnel, originally built as a shelter during World War II, had been largely abandoned following the war’s end. Connecting Radićeva and Mesnička streets, the tunnel is 350 meters long and three meters wide.

It provided some shelter during the nineties war but wasn’t essential because, as I noted, while the Serbs launched missiles at the city, Zagreb came through that period unscathed at least relative to some of the other cities we’d seen. Though it had fallen into disuse, the Grič tunnel managed to gain some notoriety during the Croatian War of Independence for being the site of the first underground rave party in Zagreb held in 1993 during the conflict.

Had we not had a guide, it’s unlikely that we would have found it or, given the unassuming entrance, probably would have chosen not to use it.

As it turns out, the tunnel has been restored to be a path for walking tours such as ours. It opened on 7 July just a little more than a month prior to our arrival. (The date of this walk is 16 August.) The restored tunnel is not only well lit

but also prepared, as one article put it, to host a range of different cultural events. There are also plans for a museum to also open inside the tunnel. The best evidence for all of this is seen here.

Yes, there are toilets in the tunnel.

Now, while it’s possible to climb stairs to the Upper Town, the easier way to get there is to ride the funicular (and by now you all should know I love me a good funicular ride). Here’s a cool fact about Zagreb’s funicular. It’s only 66 meters long making it not only Europe’s shortest funicular but one of the shortest public transportation funiculars in the world.

From the top of the funicular, a good bit of Zagreb looks like this:

You can easily see the demarcation between Donji Grad and Novi Zagreb (New Zagreb).

Finishing the walking tour.

Now it’s time to take a look at a few of the other sights we saw after our group gathered at the top of the funicular. We started in the main square of the Upper Town – St. Mark’s Square. At the center of the square stands St. Mark’s Church. There’s evidence in the form of a Romanesque window on the south side of the church that indicates it was built sometime in the 13th century. However, the church was radically reconstructed late in the 14th century and now has a late Gothic three nave structure. It’s particularly noteworthy for its tiled roof.

The pattern on the left is the coat of arms of the Triune Kingdom of Croatia, Slavonia, and Dalmatia.

(Take a deep breath because this is going to be a bit of a sprint. In 1745, the Ottomans were driven out of a chunk of territory in the eastern part of today’s Croatia. This territory became the Kingdom of Slavonia. In 1804 on the west side of today’s Croatia, the Austrian Empire annexed the Venetian Republic and in 1814 established the Kingdom of Dalmatia. The Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 created the Austro-Hungarian Empire and in 1868, the Kingdom of Croatia and Kingdom of Slavonia were joined into the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia within the Lands of the Crown of St. Stephen in the Hungarian part of the Empire. The Kingdom of Dalmatia remained in the Austrian part of the Empire. The new Kingdom in the east claimed the Kingdom of Dalmatia as the remaining Croatian land in the Empire. It often referred to itself as the Triune Kingdom of Croatia, Slavonia, and Dalmatia.)

On the right, you see the coat of arms of the city of Zagreb.

Two other buildings occupy an important place on the square. The columns visible in the very lower left of the photo are part of the Croatian Parliament building. On the opposite side of the square is this building:

This is the banski dvori or presidential residence. You should recall that this was one of the first casualties of Serbian shelling of Zagreb.

Just a short walk from Saint Mark’s Square we’ll move on to Kamenita street. The main attraction there is the Stone Gate and I’ll get to that in a moment. But first let me point out the unassuming building on the right. It’s another pharmacy (recall the pharmacy in Dubrovnik) and it’s the oldest in Zagreb. It has been in operation since 1355 and it’s said that the great grandson of Dante Alighieri worked there. I peered inside with my camera.

In reading about the Stone Gate, I concluded that it’s had a rather catlike existence because it has escaped demolition several times in its 750-year life. Recall that King Béla IV granted Gradec the status of free royal city in 1242. Although the first official mention of the Stone Gate appears in 1429, it’s known that the city walls with three gates were built between 1242 and 1266. The Stone Gate was damaged by fire on four separate occasions – 1645, 1674, 1706, and 1731. It’s this last fire that is of particular importance in the gate’s history.

The gate was surrounded by several houses one of which contained a picture of the Virgin Mary with the baby Jesus. The house burned but the painting survived untouched and its survival was deemed miraculous. The citizens of the town then built a chapel on the site where the painting is housed to this day. But wait, there’s more that the Stone Gate had to survive. My reading disclosed at least four instances when the city council proposed the gate’s – demolition generally for the purpose of widening the street to make passage easier. The first came in 1841. It was followed by similar proposals in 1871, 1878, and sometime in the first decade of the 20th century. However, each time someone proposed razing the gate, the citizens prevented it.

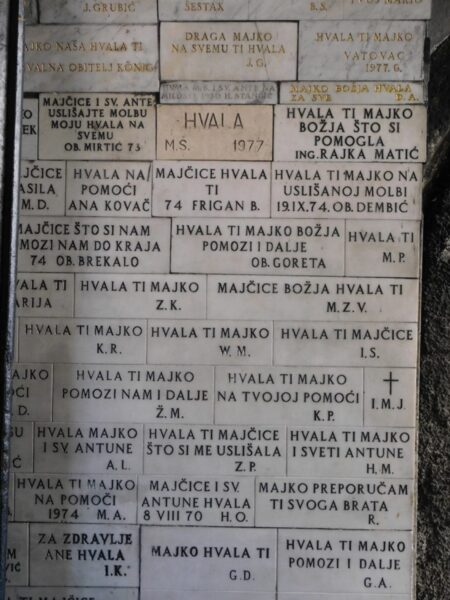

You see, the gate had become perhaps the most significant place in the city for its Catholic citizens to light candles as a token of gratitude for a prayer being answered. So staunch was this belief that even during Yugoslavia’s officially atheist communist period citizens continued to visit the site. The pavement and walls are lined with tiles with inscriptions of gratitude.

If you want to be reminded how to thank someone in Croatian, look almost anywhere in this photo and find the word hvala.