Phantasmagoria and again a bit of a Danse Macabre.

Unless you have a guide like David Downie or very specific interest, chances are that on your visit to Père-Lachaise you will overlook the very interesting and very curious tomb of the very interesting and very curious Étienne-Gaspard Robert who was also known by his stage name – Robertson.

Robertson’s grave site is both grotesque and compellingly intriguing if you stop and look closely at it. Although it stands taller than most, if not all, of the other graves nearby, Père-Lachaise is filled with so many works of sepulchral art that this one becomes evocative only when you closely examine the relief sculptures that adorn it.

Born 15 June 1763 to a wealthy merchant family in Liège, Belgium, Robertson was a precocious child who, from an early age, displayed an abiding interest in the two areas that would come to be the focus of his life – science and the macabre. In one of his Memoires (he wrote at least two) he wrote,

Who has not believed in the devil and werewolves in his early years! I confess frankly, I believed in the devil, in evocations, in enchantments, in infernal pacts, and even in the brooms of witches; I thought an old woman, my neighbor, was, as everyone assured, in regular commerce with Lucifer. I envied his power and his relationships; I locked myself in a room to cut off the head of a rooster and force the prince of demons to show himself to me; I waited for seven to eight hours, I molested, insulted, jeered that he did not dare to appear: “If you exist, I cried, slapping my table, get out of where you are, and lets see your horns, or I deny, I say that you’ve never been.” It was not fear, as we have seen, that made me believe in his power, but the desire to share it to also operate magical effects.

(It might be appropriate simply to play this music on a loop as you read this and the next section.)

As a young man, he moved to the city of Leuven (a city you might know because today it’s the headquarters of Anheuser-Busch In-Bev) where he studied philosophy and optics while also displaying some artistic skill particularly in his drawings of insects – the study of which was another area of interest for him.

When he returned to Liège, he began working with a local optical instrument maker named Villette. His drawings and his scientific curiosity so impressed Villette that the older man encouraged Étienne to go to Paris where he could better pursue both interests. In a decision that disappointed his parents who wanted him to become a priest, Étienne followed Monsieur Villette’s advice and set off for Paris early in 1789.

About halfway through his journey, Robert stopped for a night at Liesse-Notre-Dame. Arriving at night, he had an experience that remained seared in his memory when he saw a village conjuror who claimed he could raise the spirit of any dead person to appear at night out in the open country. Robert watched the demonstration and immediately understood the magician’s trick. The lesson he took with him was the ease with which willing people could be duped.

Once in Paris, Robert began working as a cameo artist and as a tutor to the children of nobility. After a time, he began to attend physics lectures given by Jacques Charles. Charles not only developed Charles’ Law describing how gases tend to expand when heated (This was formally published by Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac in 1802 but he credited it to unpublished work by Charles.) but he also – with two Robert brothers unrelated to Étienne – launched the first hydrogen filled balloon on 27 August 1783. (The launch took place on the Champ de Mars where the Eiffel Tower stands today and among the crowd witnessing the event was the Minister to France from the United States of America, Benjamin Franklin.) Charles’ interest in aeronautics sparked a similar passion in Robert.

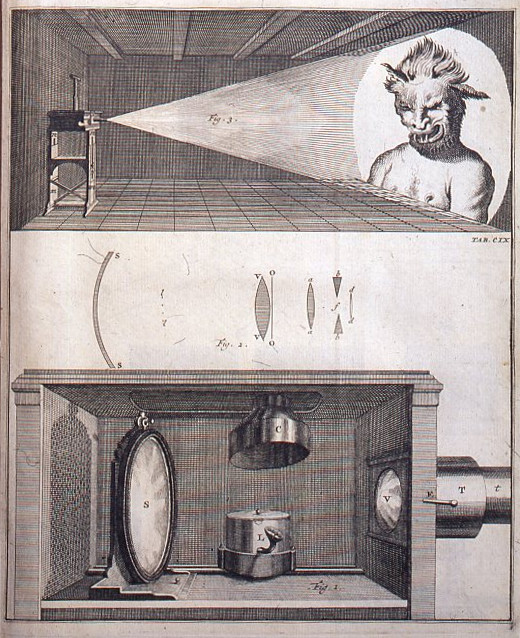

Bear with me for a few moments when I take you back to 1645 when a German Jesuit named Athanasius Kircher included a description of one of his inventions in Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae (The Great Art of Light and Shadow) – one of 40 books this brilliant scholar published. He called this particular invention the “Steganographic Mirror.” This was a projection system using a focusing lens and text or pictures painted on a concave mirror reflecting sunlight that was mostly intended for long distance communication. Fourteen years later the Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens incorporated some of Kircher’s ideas in his invention of the magic lantern.

(You should think of the magic lantern as the progenitor of the slide projector. Early iterations of the device projected images using pictures painted on transparent plates made of glass. It used a concave mirror behind a light source to direct as much of the light as possible through a small rectangular sheet of glass on which was painted the image to be projected into an adjusting lens at the front of the apparatus. The adjusting lens focused the plane of the slide at the distance of the projection screen, which could be simply a white wall, forming an enlarged image of the slide on the wall.)

[From a 1720 book showing Jan van Musschenbroek’s magic lantern projecting a monster. – Wikipedia – Public Domain.]

Though he had ongoing associations with families in the nobility, Robert stayed in Paris through the early years of the Revolution and is said to have witnessed the executions of both Madame du Barry and Marie Antoinette. More important to his future, he also witnessed a magic lantern show in 1793 by Paul Philidor. Sometime after that, he fell ill and returned for some time to Liège to recover. It was during this time that he turned his mind to developing his own show combining his talent for art and his knowledge of science to create a new, more terrifying magic lantern show the phantasmagorie or phantasmagoria. According to Wikipedia,

Phantasmagoria was a form of horror theatre that (among other techniques) used one or more magic lanterns to project frightening images such as skeletons, demons, and ghosts onto walls, smoke, or semi-transparent screens, typically using rear projection to keep the lantern out of sight. Mobile or portable projectors were used, allowing the projected image to move and change size on the screen, and multiple projecting devices allowed for quick switching of different images. In many shows the use of spooky decoration, total darkness, sound effects, (auto-)suggestive verbal presentation and sound effects were also key elements. Some shows added all kinds of sensory stimulation, including smells and electric shocks. Even required fasting, fatigue (late shows) and drugs have been mentioned as methods of making sure spectators would be more convinced of what they saw. The shows started under the guise of actual séances in Germany in the late 18th century, and gained popularity through most of Europe (including Britain) throughout the 19th century.

I’ll pick up the story of how Robert used the phantasmagoria in the next post.