As I noted in the post about Pisaq, researching the material in these posts is something of a pre and post-travel temporal stew. If I expect it’s a subject I’ll cover in depth I’ll have compiled tens of pages of notes prior to departing. After the trip I read them, decide what I’ll include, what I need to supplement, and what I’ll discard.

In other instances, I might only have a general idea about the place or its people in advance of my departure. The ruins at Tiwanaku are a good example of that. I’d read somewhere about the archaeological site near La Paz and thought it might be an interesting place to visit but I knew nothing about the Tiwanaku culture before going there. Sometimes there’s a place on my itinerary that generates either a pre-trip shrug or a sort of exploratory indifference. Then, an intense experience adds significant post trip seasoning to my research stew. Every place we visited in the Sacred Valley represented this sort of place. None more so than Ollantaytambo.

Unprepared in more ways than one.

In the final itinerary JLA sent about my trip the complete description of our day read: “Visit the beautiful Sacred Valley, seeking out Inca temples and fortresses.” Thus, when we reached Ollantaytambo (correctly pronounced Oh-yahn-TIE-tahm-bo), I had no idea the site beyond the market would look like this.

(This and most of the photos of Ollantaytambo come courtesy of Jan. Once again, my camera batteries died and I hadn’t toted any replacements and my phone is a far better phone than it is a camera.)

The overcast skies at the time of our arrival dull the impression this place makes in sunshine when it has an ethereal glow. I had a stronger reaction when I first saw the so-called fortress of Ollantaytambo than I’d had at Mount Rushmore. It looked as though the Inkas simply carved their way up the mountain and built structures that, more than most we’d seen, appear to rise organically from the contours of the hills.

Notice that I called Ollantaytambo a “so-called fortress.” Like every other Inkan mystery, we cannot be certain of the purpose of this multi-faceted and unfinished complex. It’s likely that at least some of the structures served a military purpose but its characterization as wholly – or even principally – military comes from the Spanish Conquistadors and undoubtedly reflects their experiences.

What’s in a name?

This is a rare instance where the present name of the town accords with its historical one. Of course, how that came to be is a matter of conjecture. The most likely explanation is that it’s a corruption of the Quechua words ullantawi meaning ‘a place to see down’ and tampu meaning ‘inn’ or ‘resthouse’.

The other alternative is tied to an Inkan folk tale of the love between a warrior called Ollanta (or Ollantay) and Kusi Quyllur a daughter of the great emperor Pachakutiq. It’s generally believed that as Pachakutiq quickly extended his budding empire into and up the Wilqamayu Valley, he began construction on the Ollantaytambo complex with its extensive terraces and sophisticated irrigation system. This is important in the story of the secret lovers. I’ve tried to cohesively cobble it together based on several different sources.

The warrior Ollanta and Kusi Quyllur were secretly married despite being from different classes that barred them from marrying. When Ollanta makes a public declaration of his love for Kusi Quyllur, Pachakutiq bans him from Cusco and sends her to the Inkan equivalent of a convent.

Ollanta retreats to the mountain complex at Ollantaytambo whence he launches a rebellion against Pachakutiq. The Emperor sends his best general Rumi Ă‘ahui to quash it but even after a decade of fighting the general couldn’t dislodge Ollanta so he devised a plan to win the war by deceit.

He pretended that the Emperor was going to punish him for his failure and arranged a meeting with Ollanta during the winter solstice festival of Inti Raymi. Rumi Ă‘ahui got Ollanta and his soldiers drunk, sprung a trap and took him prisoner.

Meanwhile, in Cusco, Pachakutiq had died and was succeeded by Tupaq Yupanqui and Kusi Quyllur had given birth to Ollanta’s daughter a child she named Imaq Sumaq. The new Sapa Inka listened to everyone’s stories and officially sanctioned the marriage. Because of his determination and bravery, the place that might have once been called Pakaritanpu was renamed in his honor.

More than a fort.

Ollantaytambo sits about 2,800 meters above sea level. The descent from Bolivian heights and better acclimitization made it easier to move around though I still needed to periodically stop to catch my breath ascending toward the Temple of the Sun. The combination of required rest and limited time made this visit similar to the one at Pisaq. This overview

from the website annees-de-pelerinage shows the overall breadth of the site. We climbed only from the area marked “Old town” to the “Templa del Sol” or Temple of the Sun. By now, the sight of agricultural terraces should be as familiar to you as they were to us so we took little notice of them. The areas we didn’t walk to are Araqama Allyu or ritual community, Incamisana (water temple), some granaries (Qolqas), and the Intihuatana – the astronomical clock. Clearly the site has a lot of territory devoted to non-military functions – mainly agriculture and ritual – thus belying a principally military purpose.

Some think the site was dedicated to water worship with archaeologists pointing out Ollantaytambo’s many similarities with TipĂłn a site southeast of Cusco best known for its large irrigation work and water channels.

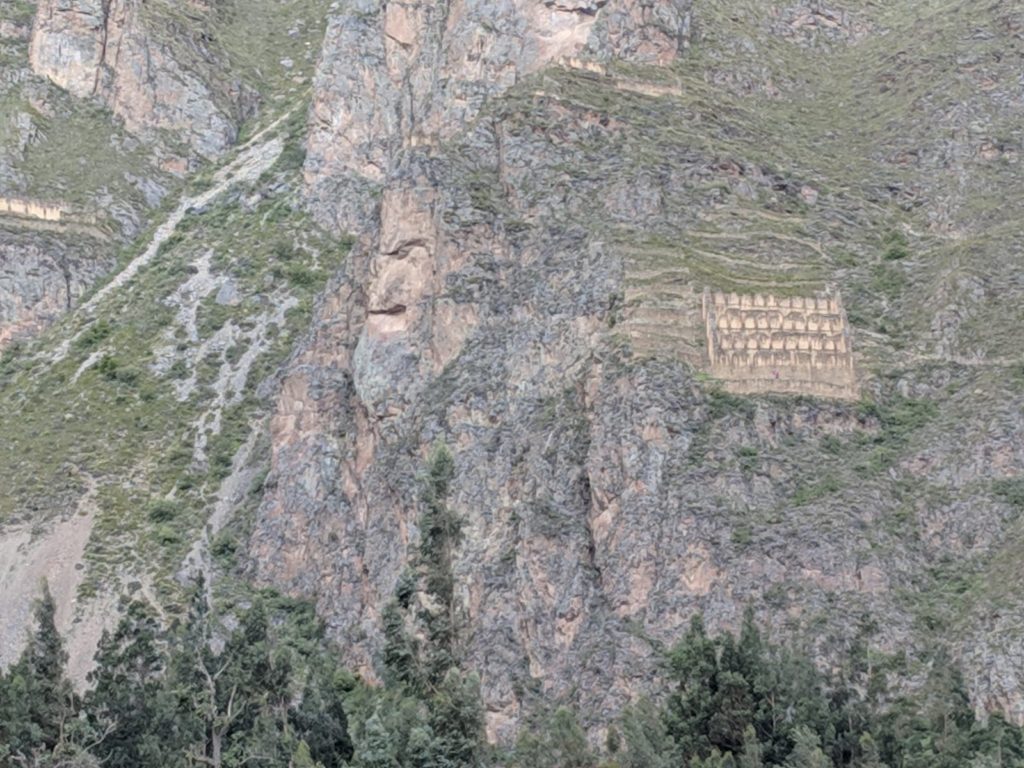

The photo above looks at the site from the west so invisible to you are the main storehouses. Let me remedy that.

The storehouses are on the right. To their left, appears a man’s face in profile. Some claim this is a carving of Viracocha. The greater likelihood is that erosion has created another instance of pareidolia. The rest of the pictures are here.

Lending credence to the notion of some military purpose, Ollantaytambo is easily defensible and is close to parts of the Inka road system that lead not only to Machu Picchu but to the Chinchaysuyu – the part of the Tawantinsuyu encompassing the Ecuadorian Rainforest. And there is, of course, the legend of Ollanta.

It was here, however in 1536 or 1537, led by Manqo Inka Yupanqui, where the Inkas achieved one of their last victories over Hernando Pizarro and the Spanish Army. The Spanish naturally concluded it was a fort.

A quick wrap-up.

See all you can in five days in Paris and I can make a list to fill another five days. Thus, I try to simply recount my experiences supplemented by areas that sparked my curiosity. Any time you travel with a schedule, you’re bound to miss exciting sites. What interests me may not interest you so I generally avoid making recommendations. This is an exception.

Visiting Cusco, the Sacred Valley, and Machu Picchu requires time to acclimatize to the altitude. Many people fly into Lima for a few days then hop to Cusco where they might also spend a day or two before moving on to Machu Picchu where they still feel the effects of the altitude. If you have the time, I’d recommend first spending at least two full days in Cusco alone. There you can see ruins, visit museums, and ease your adjustment to the altitude.

Then, using Cusco as your base, I’d suggest spending a full day visiting Chinchero. (For people who like to shop, try to go on Sunday when they have a lively market that functions largely on barter for fruits, vegetables, and their famous textiles.) Next, try to arrange a full day to explore Moray and Maras. Spend yet a third day at Pisaq. It’s only an hour’s drive from Cusco so you can once again return there after your visit. (If this seems to be too much, the key is allowing enough time to see these places without feeling as though you’re rushing from one to the other.)

Finally, Ollantaytambo is about two hours by van from Cusco. Get an early start so you arrive when the site opens and challenge yourself with some hikes if you’re up to it while also leaving time to explore the town because it’s probably the closest example you’ll find to a living Inkan village in terms of its architecture, roads, and lifestyle. Stay there overnight as we did then take the train to Aguas Calientes for your visit to Machu Picchu.

The video below (which I’ve started at the 9- or 10-minute mark) provides some inspiring visuals.

Revealing my mind again.

Some of you might have connected the pun in the title of today’s post to the song it references. Conversely, because it has as little connection to reality as the one I made between Arromanches and “My Romance” or Bolivia and “Lydia the Tattooed Lady” some of you might need some help. Here it is.