Notes on the XXI Winter Olympiad – Vancouver 2010 (Vancouver and Me addendum one)

A curious choice.

At first glance (and even at a second glance) Vancouver seems like an odd choice to host the Winter Olympics given that the average low temperature in December and January – the city’s two coldest months – never dips below freezing (2° C or 36° F) and the average high is about 6° C or 43° F. It’s marginally warmer still during the event’s scheduled February dates (12 through 28). Even its partner town in the bid, the Coast Mountains ski resort town of Whistler where the mountain sports were located struggles to get below freezing and can have as much February rain as it does snow. In fact, the weather was so poor leading up to the Games that it forced the cancellation of training runs at both skiing venues and delayed the first Alpine event – men’s downhill – by two days forcing others to be rescheduled.

While Whistler, some 121 kilometers (75 miles) north of Vancouver eventually managed enough snow to host its events, Cypress Mountain the closer to Vancouver venue for snowboard and freestyle skiing imported truckloads of snow from Manning Park about 250 kilometers (160 miles) to the east of the city.

John Furlong was the chair of the Vancouver Olympic Organizing Committee (VANOC) and it appears that Mister Furlong was able to work out, shall we say, a questionable arrangement to help bring the Games to British Columbia.

[Photo from Wikimedia Commons – Dave O from North Vancouver CANADA-CC-BY-SA-2.0.]

Although he was cleared of any wrongdoing by an International Olympic Committee (IOC) investigation, Furlong wrote in his memoir that he and Bob Storey, another VANOC official, met with Moscow mayor Yuri Luzhkov in his office near Red Square ahead of the IOC vote in June 2003. He states they reached a deal that involved the Vancouver team arranging a special Olympic bidding workshop for the Russians in exchange for votes from Russia’s IOC members.

Furlong’s book claimed that six or seven IOC members’ votes were potentially involved in the deal, but according to the IOC investigation “in reality the number was three.” Three was still enough. The final round of the IOC vote gave Vancouver 56 votes and the remaining city P’yŏngyang, North Korea 53.

(Depending on your point of view, Furlong has a character you will either admire or despise – or perhaps a bit of both. On one side he emigrated from Ireland to Prince George, British Columbia in 1974. There, he became a teacher and athletic coach at Prince George Catholic High-School where more than 80% of the students were aboriginal. Such Catholic schools across Canada were notorious for incidents of physical, psychological, and sexual abuse. They forcefully replaced First Nation languages with English, stripped Native culture and belief systems, and replaced them with forced conversion to Christianity. The degree to which Furlong participated in these activities, if any, is up for debate.

On the other side, Canadians admire Furlong enough to honor him with the Order of British Columbia and enshrine him in the BC Sports Hall of Fame mainly for his work in bringing the Games to Vancouver.)

John Furlong and the Terrible; Horrible; No Good; Very Bad Day.

The torch relay mishap:.

I’ll get this bit out of the way: John Furlong chaired the Vancouver Olympic Organizing Committee (VANOC) and, even without the tragedy, the opening day of the Games would have been close to disastrous.

You might recall that the Olympic Torch Relay for the 1984 Los Angeles Games covered 15,000 kilometers and passed through 33 states and the District of Columbia. The Canadian plans for Vancouver’s torch relay sent the torch over 45,000 kilometers or nearly 28,000 miles although less than 10 percent of the distance was actually covered on foot.

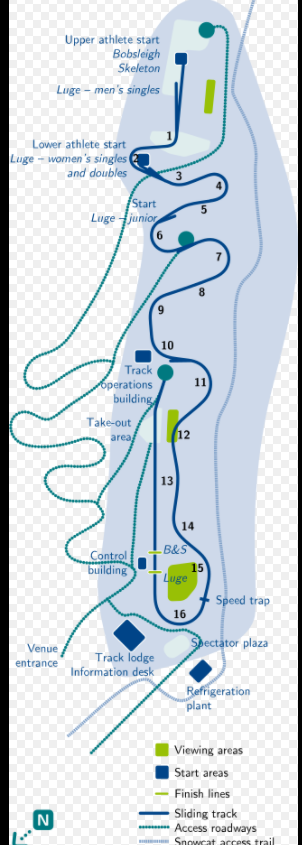

[Map from Olympics.com.]

After its arrival in Vancouver from Greece on 30 October 2009, the torch began the circuitous journey that would take it through every province and territory of, by area, the second largest country in the world. On 8 November, the flame arrived by air in Alert – a mere 817 kilometers from the North Pole in the territory of Nunavut. It’s the northernmost permanently inhabited place in the world. Although the latter doesn’t appear on the map, the flame passed through both Montreal and Calgary the two previous Canadian host cities.

The torch returned to Vancouver and the University of British Columbia on 11 February with the Opening Ceremonies scheduled for the next day. In what they no doubt thought was an innovative stroke, the organizers planned for the Ceremony to be held at BC Place making it the first Opening Ceremony to be held indoors.

Not all Canadians (let alone British Columbians) were thrilled to have the games held in Vancouver. Indigenous people, environmental activists, and a range of other protesters descended on the city. While the protests would spill into vandalism on the thirteenth – the first official day of competition –

[Photo from CBC.]

protesters were out in such force on the day of the Opening Ceremony that VANOC had to alter the planned route from the university to the arena.

The torch lighting mishap:.

The Opening Ceremony of every Olympic Games ends with the lighting of the Olympic Flame that will burn throughout the duration of the Games and Vancouver was to be no exception. As the three hour Ceremony neared its close, five of Canada’s greatest Olympic athletes – wheelchair athlete Rick Hansen, hockey great Wayne Gretzky, skier Nancy Greene Raine, NBA star Steve Nash, and speed skater Catriona LeMay Doan – each bearing a torch were to be lifted together from the arena floor on a series of pillars to light the cauldron in unison. However, LeMay Doan’s pillar malfunctioned bringing the Ceremony to a halt as engineers tried to address the problem. Eventually, she walked onto the surface and saluted the crowd with her torch.

In a rather ironic touch the cauldron at BC Place was extinguished shortly after the end of the Opening Ceremony. The VANOC had an identical cauldron at Jack Poole Plaza in Coal Harbor. This second flame, lit by Gretzky was the one that burned throughout the duration of the games. The BC Place cauldron was relit so it burned during the Closing Ceremony and was extinguished again, this time simultaneously with the cauldron at Jack Poole Plaza.

The real tragedy:

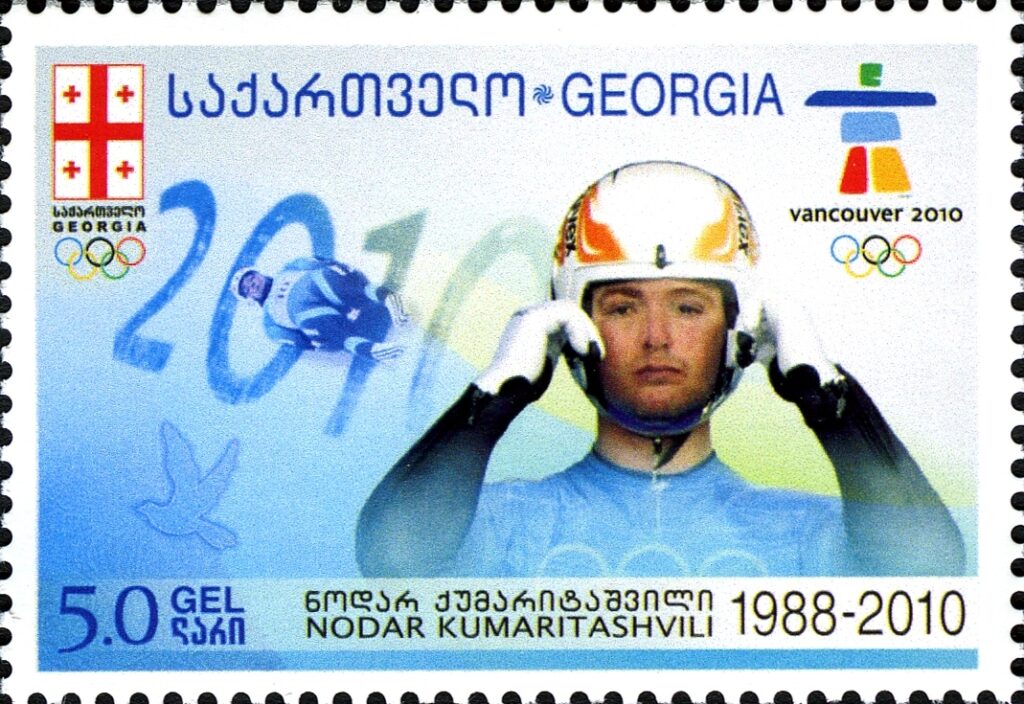

All of this would have likely provided fodder for comedians had the day of the Opening Ceremony not been marred by the death on a practice run of Georgian luge racer Nodar Kumaritashvili. Although accidental, many believe that the accident was foreseeable and preventable.

The Whistler Sliding Centre faced controversy from its conception because parts of it were constructed on First Nations spiritual land. Nevertheless, it opened for testing on 19 December 2007 and although both the International Luge Federation (F I L) and the International Bobsleigh and Tobogganing Federation (FIBT) provisionally certified it in March 2008, a foreshadowing of the trouble that would follow arose in its earliest days.

[Image from Wikimedia Commons BY-Lumu-talk-Own-work-CC-BY-SA-3.0.]

Attempts to fine tune the track continued into December 2008 but F I L President Josef Fendt, seeing top training speeds reaching 149 km/h (93 mph), worried publicly that the track’s speed was too high. German luger Felix Loch, the 2008 world champion, suffered a serious shoulder injury during a World Cup training run. He noted luge speeds for men’s singles reached 100 km/h (62 mph) before turn three at the women’s singles and men’s doubles’ start house.

Nearly a year before the start of the Olympics, John Furlong expressed a fear that athletes could still get “badly injured or even worse” on the luge track. After early testing the F I L requested major changes to six curves on the luge track including curves 15 and 16. This was the section of the track that led to Kumaritashvili’s death.

Fendt wrote a letter to the designer of the track noting that it was recording “historic sled speeds” that were nearly 20 kilometers an hour faster than the track designer had anticipated. The rules of the FIBT limits to five the g-force exerted on racers. A CBC investigation found a g-force of 5.02 possible for male lugers on the track in Whistler.

The F I L conducted an investigation with a report issued in April 2010 concluding that Kumaritashvili’s mistakes primarily caused his death citing, according to a report on ESPN, gravitational forces that “overpowered out-of-control Georgian luger Nodar Kumaritashvili and left him unable to avoid the crash.” The report further stated that Kumaritashvili exited the 15th curve in the 16-turn course too late, causing him to take a less-than-favorable line into the final curve and that energy threw Kumaritashvili upward and over the opposite side of the track, milliseconds after he was clocked at 144 km/h (89.4 mph).

American slider Tony Benshoof had his Olympic race suit signed by all 10 members of the American team and placed it on auction on E-Bay to raise money for Kumaritashvili’s family.

As for the Olympics, there was a moment of silence in his honor at the Opening Ceremony. Kumaritashvili was 21.

-

It’s just a shot away – Prizren

March 6, 2026 -

Some things looking better, baby – Getting into Kosovo

March 4, 2026 -

Here, where the sky is falling – Kukës

March 2, 2026 -

That’s when we fall in line ’cause we got Berat

February 27, 2026 -

Walking on the big stuff – a climb to Tragjas

February 25, 2026