In the introduction to the post about the 19oo Olympic Games I teased two stories about the 1924 Games. The first focused on a pair of dates in 1981 and 1982 when one story from the Games of the VIII Olympiad came to prominence in the American – and possibly the world’s -consciousness. The second hinted at a story I think is even better. The first date was 25 September 1981 and, while people in the UK had seen and heard this several months earlier, it was the first chance for the American public to enjoy

the stories of Harold Abrahams and Eric Liddell. On 29 March 1982, Chariots of Fire, this somewhat fictionalized account of their competition, went on to win the Academy Award for Best Picture of 1981. For those who are somehow unfamiliar with this story, I’ll provide a brief summary below. I’ll also get to that more remarkable tale at some later point. But first, let’s take a broader look at Paris 1924. (The opening scene in the above excerpt was filmed at West Sands a beach adjacent to the Old Course of the Royal and Ancient Club at Saint Andrews and the exterior of the ‘Carlton Hotel’ is actually the R & A Clubhouse.)

And I grew strong,

And I learned how to get along.

After the chaos of 1900 and the confusion and minor debacles of 1904, the Olympic movement took two steps forward in London in 1908 and Stockholm in 1912 before taking one step back when the 1916 Games, scheduled to be held in Berlin, were canceled due to the First World War. So in 1920, Baron de Coubertin had to be thinking, “Thank goodness for Antwerp.” The Belgian capital hosted the Games a mere two years after being occupied by German forces in World War I where it instituted the tradition of the athletes’ oath and the five ringed Olympic flag designed by de Coubertin himself made its first appearance.

The 1924 opening Ceremony took place in the Stade de Colombes

[Photo from Wikipedia by Frederic rugbypioneers.com CC 2.0.]

which also hosted athletics, gymnastics, rugby union, and the football final among other events.

Although the 1932 Los Angeles Games had the first formally constructed Olympic Village, the term was first applied in Paris in 1924 to a small number of cabins built close to the Stade de Colombes.

Held in association with the 1924 Summer Olympics, a series of sports competitions in Chamonix between 25 January and 5 February 1924 called Semaine des Sports d’Hiver (Week of Winter Sports) later became designated by the IOC as the first Olympic Winter Games.

The 1924 Games were the last organized with de Coubertin as the President of the IOC.

The 44 National Olympic Committees and 3,089 athletes set new participation records.

Rather than being held in the Seine as happened in 1900, the swimming competition for the first time used a standard 50 meter pool with lane markings.

The 1924 Games introduced the closing ceremony ritual of raising three flags – the flag of the IOC, the flag of the current host nation, and the flag of the next host nation.

Standout Athletes.

The great Paavo Nurmi, called the Flying Finn, surpassed his total of three gold medals that he won in Antwerp by capturing five at Paris in 1924.

[Photo of Paavo Nurmi from Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain.]

Nurmi won individual gold in the 1,500 meters, the 5,000 meters (which was run just two hours after the 1,500 final), and individual cross country while being a member of Finnish teams that won gold in the cross country and 3,000 meters.

Harold Osborn set a pair of Olympic records in winning his two gold medals. His record leap of 6′ 6″ in the high jump remained the Olympic record for 12 years. (Another American, Leroy Brown took the silver. None of my research has confirmed the degree of his badness.) Osborn, who had lost most of the vision in one eye in a childhood accident used a unique jumping style that came to be called the “Osborn roll.”

Meanwhile, Osborn’s decathlon score of 7,710.775 points set a world record. Setting two world records resulted in press coverage declaring him the “world’s greatest athlete.”

In that standard 50 meter lane delineated pool, American Johnny Weismuller claimed three gold medals and one bronze. His two individual medals came in the 100 and 400 meter sprints and he also captured gold in the 4 x 200 relay. The bronze medal came from being a part of the water polo team. Weismuller would return to the Olympics in 1928 in Amsterdam to successfully defend the 100 meter and relay golds he won in Paris. After returning to the U S Weismuller got his big Hollywood break in 1932 when he took the titular role in the film Tarzan the Ape Man – a role for which he originated this:.

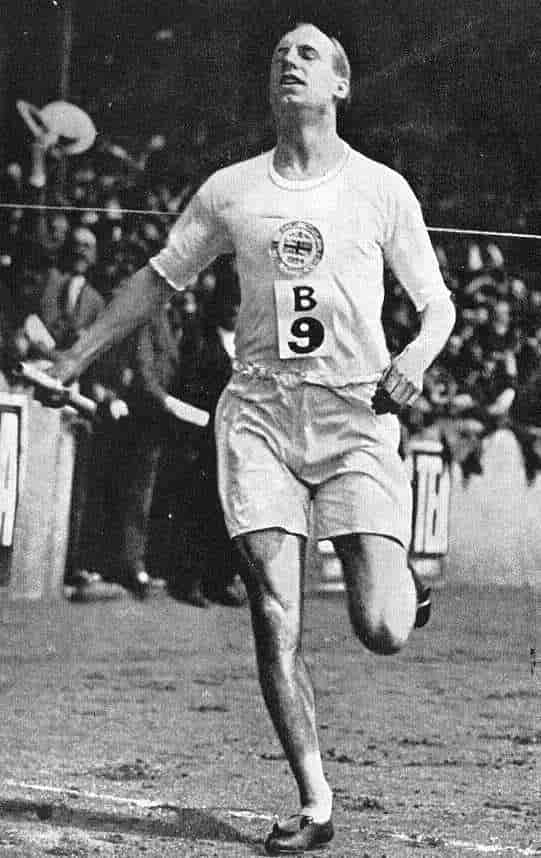

In the sprints, the UK’s Harold Abrahams and Eric Liddell won the 100 and 400 meters races respectively.

With a winning time of 10.6 seconds, Abrahams became the only Englishman to win the sprint crown until Linford Christie’s victory in 1992.

[Photo of Harold Abrahams Wikipedia – Public Domain].

(Scotsman Alan Wells had his controversial victory in Moscow in 1980 under the flag of the UK but he was most certainly not English.)

Liddell, who was also an accomplished rugby union player, famously refused to run in the 100 meters final because it was held on a Sunday. He won the gold medal in the 400 meter race and his winning time of 47.6 seconds set new Olympic, European, and British records.

[Photo of Eric Liddell from Wikipedia – Public Domain.]

As for the movie, let’s say it took some creative license.

Early in the film we see Abrahams challenging the Great Court Run at Trinity College. There’s neither a record nor a report of Abrahams ever attempting it. It was filmed not at Trinity but at Eton’s school quad.

When Abrahams attends a performance of The Mikado and falls for its star Sybil Gordon, he’s falling for the wrong Sybil. Sybil Gordon was a singer for the D’Oyly Carte Opera Company but Abrahams fell for another D’Oyly Carte singer – Sybil Evers. He actually met her in 1935 – 11 years after the Olympics and married her in 1936.

One of the moments of high drama occurs on board a ship as the UK team is on its way to Paris. In the film, it’s at this time that Liddell learns that the 100 meter final was scheduled for Sunday and refuses to run because of his religious principles. The latter part is true. The former is not. The schedule had been public for months and everyone knew that he would compete only in the 200 and 400 meter races long before they boarded that ship.

In another moment of high drama we see Sam Mussabini massaging Abrahams after he’d been beaten “out of sight in the 200” and Abrahams using it as motivation for the upcoming 100 meters. The problem is that while Abrahams indeed faired badly in the 200 the race came after his win in the 100.

We also see Mussabini sitting outside the stadium in the training room punch through his straw hat upon hearing God Save the King signaling Abrhams’ win. However, you might recall that according to both the Guinness Book of World Records and the Olympic Games Museum, this tradition of playing the winner’s national anthem began in Los Angeles in 1932.

Abrahams actually died just a few days after beginning to work with producer David Puttnam and writer Colin Welland and attending his memorial service sparked the idea for the framing of the film.