General Phillip Sheridan, who also unsympathetically prosecuted many battles in the west, recognized the role of both the government and the railroad in forcing the indigenous people onto reservations with no compensation beyond the promise of religious instruction and basic supplies of food and clothing – promises which, he acknowledged, were never fulfilled. In 1878, in his Annual Report of the General of the U.S. Army he wrote,

“We took away their country and their means of support, broke up their mode of living, their habits of life, introduced disease and decay among them, and it was for this and against this they made war. Could any one expect less? Then, why wonder at Indian difficulties?”

Although this wasn’t the case, Sheridan could have been writing specifically about the Blackfeet. Smallpox epidemics, military skirmishes, and the extermination of the buffalo, all contributed to a drastic population loss among the Blackfeet. The year 1883 proved to be particularly devastating. It began a series of starvation winters, where the routine delay and frequent failure of the government to deliver rations guaranteed by the Lame Bull Treaty of 1855 which had also first set the boundaries of the Blackfeet Reservation (and that reduced their traditional territory by more than 90 percent), led to the deaths of over one-quarter of the tribe.

Desperate to raise funds for food and basic supplies, the tribe began selling pieces of their remaining land to the federal government. In 1895, they sold 800,000 acres west of the current reservation. The 1895 Agreement between the United States and the Blackfeet Nation of Montana transferred the title of the eastern portion of the Rocky Mountains to the United States in anticipation of mineral exploitation. The Blackfeet tribe settled for 1.5 million dollars while retaining the right ‘to go upon the land’ and to hunt and fish and to harvest sacred plants and wood. After mining booms went bust these lands would form the eastern half of Glacier National Park in 1910.

The language of the 1895 Agreement specifically provides that

said Indians shall have, and do hereby reserve to themselves, the right to go upon any portion of the lands hereby conveyed so long as the same shall remain public lands of the United States, and to cut and remove therefrom wood and timber for agency and school purposes, and for their personal uses for houses, fences and all other domestic purposes: And provided further, That the said Indians hereby reserve and retain the right to hunt upon said lands and to fish in the streams thereof so long as the same shall remain public lands of the United States under and in accordance with the provisions of the game and fish laws of the State of Montana.

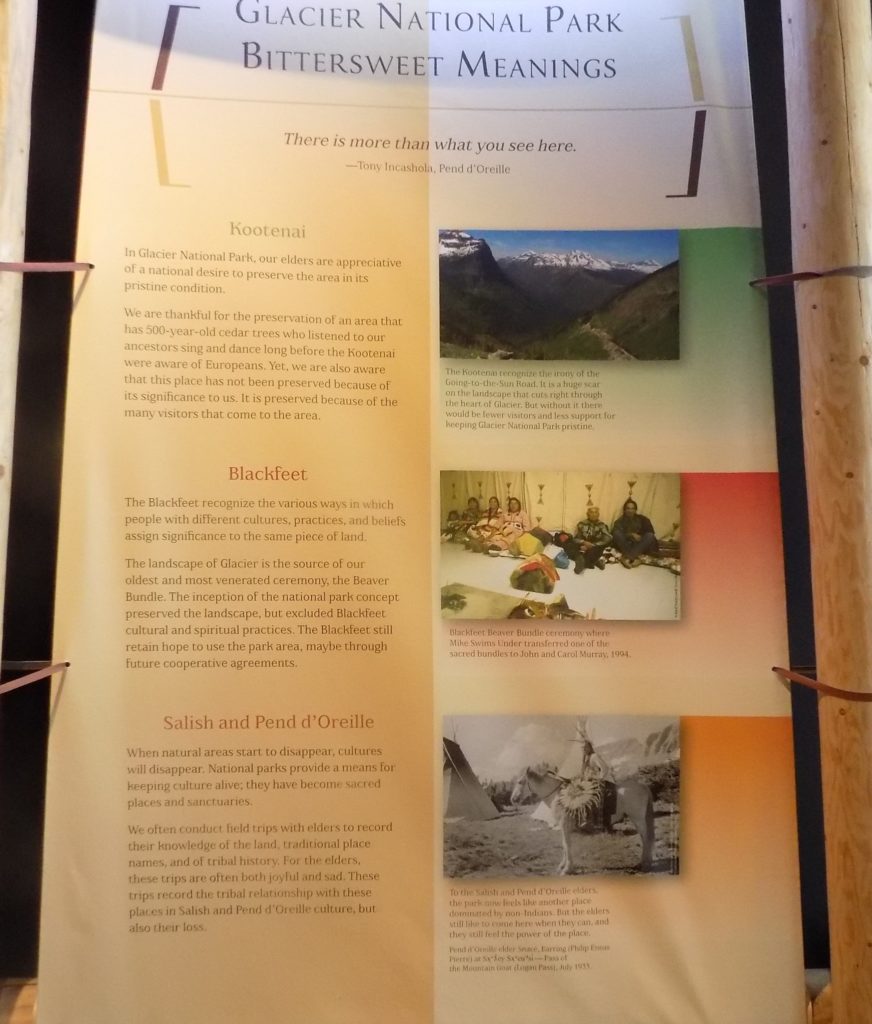

Many in the Blackfeet community believe this language provides them with certain rights to the land and its use as this display in the St. Mary Visitor Center shows.

It certainly seems that such would be the case. However, in a case that came before a US District Court in 1932, the court issued a ruling that the designation of the land as a national park extinguished the rights specified under the 1895 Agreement. The court concluded that the land in question ceased to be “public land” once it became a national park and was no longer “subject to sale or other disposal under general law.” The court also claimed that, “The Blackfeet had failed to establish the extent to which they used the reserved privileges from 1895 to 1910” and had therefore forfeited these rights.

Two subsequent court decisions have left the situation open to dispute and interpretation. In 1973, Judge Donald Kipp upheld the right of Blackfeet tribal members to enter the park for free. In a subsequent suit, he denied three tribal members the right to fire a gun, fish in a closed area, or cut a limb from a tree citing the 1932 decision in his ruling. (Charles used this right of free access to bring the entire bus into the park.)

Halfway to the barely seen sun and mountains

Chasing the legend of Wild Goose Island

Among the first places we stopped on our way to Logan Pass was the viewpoint for Wild Goose Island. According to Wikipedia, although the island rises merely 14 feet above the lake’s surface and “is dwarfed by the lake and surrounding mountains,” it is nevertheless “one of the most frequently photographed locations along the Going to the Sun Road.”

The website Americanfolklore.net provides this legend about its name:

A Montana Legend

retold by S.E. Schlosser

In the middle of St. Mary Lake in Glacier National Park is a small island halfway between two shores. Many moons ago now, there were two tribes living on either side of the lake. While there was no direct warfare between them, the two tribes avoided one another and had no dealings one with the other.

All this changed one day when a handsome warrior on the near shore saw a lovely maiden from the other tribe swimming toward the small island in the middle of the lake. He was instantly smitten by her beauty and leapt into the lake to swim to the island himself. They met on the shore of the little islet, and the maiden was as taken with the warrior as he was with her. They talked for hours, and by the end of their conversation, they were betrothed. After extracting a promise from his beloved that she would faithfully meet him at the island on the morrow, the warrior swam home to his tribe, and she returned to hers.

Oh, what an uproar they met upon their return. Neither tribe was happy at their meeting, and all were determined to break the betrothal instantly. What to do? The man and the maiden had no doubts at all. In the wee hours of the morning, each swam out to the little island to meet one another — from their to flee to a new land where they might marry. As soon as they were discovered missing, warriors from both tribes set out in pursuit, to bring the renegades back by whatever means available.

But the Great Spirit was watching, and took pity on the young lovers. He transformed them into geese, which mate for life, so they could fly away from their pursuers and so that they would always be together. When the warriors arrived on the island, the found not a man and a woman, but two lovely geese walking among the small trees and bracken. At the sight of the warriors, the two geese stroked their necks together lovingly and then flew away, never to return.

From that day to this, the little island at the center of St. Mary Lake has been known as Wild Goose Island.

This is what we saw

and this, one of a handful of photos Charles kindly emailed me, was what we should have seen.

Similarly, there’s our look at the upper portion of St. Mary Lake from Sun Point

And this similar one from the World Wildlife Fund’s Good Nature Travel site

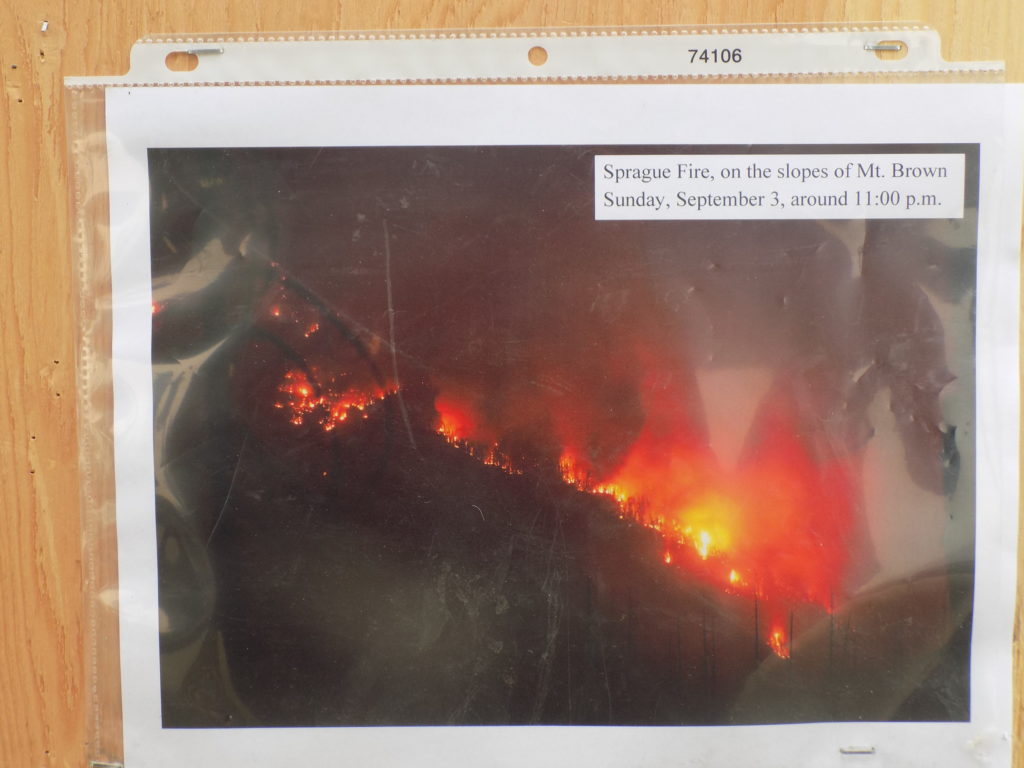

When we arrived at Logan Pass, the permitted limit of our travel, we had the chance to see some photos of what was happening on the park’s west side.

Our stop at Logan Pass did provide the opportunity to see some Glacier NP wildlife.

This is a Columbian ground squirrel and it is only with my tongue loosely in my cheek that I point it out as my Glacier NP wildlife moment. According to the Visitor Center, this little critter spends 70 percent of the year hibernating so there’s only a three-and-a-half-month window to see it. The rest of my photos (for what they’re worth) are here.

And yes, I intended this post’s title to evoke this song.

I’ll wrap up the trip in the next posts which will feature the final appearances of Chris, Wendy, and Stephanie and my decision to throw in the towel.