Looking around Judenplatz (Jewish Square) today it’s hard to fathom the extent of Austria’s long dark history with its Jewish population and the horrors that happened here. Take the short walk from Hoher Markt to Judenplatz, enter the square through the narrow Jordangasse, and the first things you’ll likely notice are the statue of Gotthold Lessing, one of the leading representative writers of the Enlightenment,

(albeit from behind and not this angle) and a little more distant, Vienna’s memorial to the 65,000 Austrians exterminated in the Nazi Holocaust

designed by Rachael Whiteread. Looking like a closed, windowless single story building, upon closer examination it appears to have been made of concrete books but with their spines turned inward. It’s also known as the Nameless Library. Keep looking around the square and at number 8 you’ll find a branch of the Jewish Museum of Vienna; at number 3-4 a plaque indicating that in 1783 Mozart lived in a house that stood in that place.

They were Hussites not Hussies

Now take a look at Number 2 – perhaps the oldest remaining house on the square with much of it dating back to the mid 16th century. Look up to see a relief of Saint George above a scene of Jesus’ baptism. Below that is a plaque inscribed in Latin.

It reads, “As the waters of the River Jordan cleansed the souls of the baptized, so did the flames which rose up in the year 1421 rid the city of all injustice.”

To understand what happened in 1421 that rid Vienna of “all injustice,” we need to look at the seed that was planted on 6 July 1415 when the Catholic Church executed a Czech Christian reformer name Jan Hus by burning him at the stake. (We’ll meet Hus again in when we reach Czechia.) Despite the efforts of King Wenceslaus IV of Bohemia to suppress his followers called Hussites, their movement continued to spread and in 1419 a series of wars between Catholics and Hussites began that embroiled Eastern Europe for 15 years.

The Hussite wars provided a convenient excuse for rampant Catholic antisemitism to flourish in Bohemia and Austria. Catholics accused Jews – in some instances justifiably – of providing money and weapons to the Hussites while Dominican priests denounced the Jews and Hussites from their pulpits. Catholic attacks against Hussites were often preceded by pogroms against the Jews.

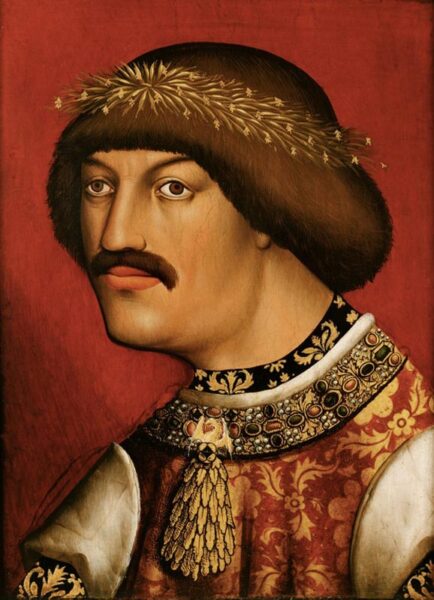

Enter Albrecht and the Wiener Gesera

The first evidence of a Jewish presence in Vienna dates to the 12th century and, by the 15th century, estimates placed the Jewish population at between 1,400 and 1,600. Albert V (Albrecht), the archduke of Austria at the time, was both something of a religious fanatic and someone who enjoyed a rather lavish lifestyle. He was aggressively engaged in the wars with the Hussites and both the wars and his lifestyle needed to be financed. This left Albert deeply in debt to Jewish financiers but without any apparent means to repay them.

(Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain)

At the time of the Easter holiday in 1420, when a rumor began circulating in a town west of Vienna that a wealthy Jew named Israel had bought Communion wafers from the wife of a church official and that they were now being desecrated by members of the Jewish community, it provided the opening Albrecht needed. He ordered the arrest of Jews from all over the country and had them brought to Vienna where the wealthy among them were forced to give up their property often under torture.

Foreshadowing what would happen in Iberia later in the century, Catholics made attempts to forcibly baptize Jewish adults and Jewish children were taken from their parents and sent to Catholic institutions for conversion. The persecutions continued throughout 1420 and into the winter of 1421 by which time only between 500-600 Jews remained in Vienna.

Sometime in March 1421 approximately 300 Jews sought refuge in the Or-Sarua Synagoge at Neuer Platz. (The square was renamed Judenplatz in 1437.) They were literally held under siege for three days before the rabbi set fire to the building resulting in a collective suicide that permitted their escape from compulsory conversion.

On 12 March 1421, Albrecht ordered the few remaining Jews in Vienna – some sources list 92 men and 120 women – taken to the so-called Goose Pasture in the Erdberg section (near St. Marx) where they were burned alive.

The archduke, who would later become Holy Roman Emperor, banished any remaining Jews in Austria and took possession of their property thereby freeing Albrecht not only from his Jewish (meaning his debt) “problem.” The edict ordering the expulsion of the country’s Jews is referred to as the Wiener Gesera (gezera is Hebrew for “decree”). The term is often used to describe the entire year of persecution and is also the name of a contemporary chronicle that serves as a source of information about the events. The ban stood for more than two centuries before Emperor Ferdinand II permitted some Jews to return and settle in Leopoldstadt (now Vienna’s second district).

The first revivification coda

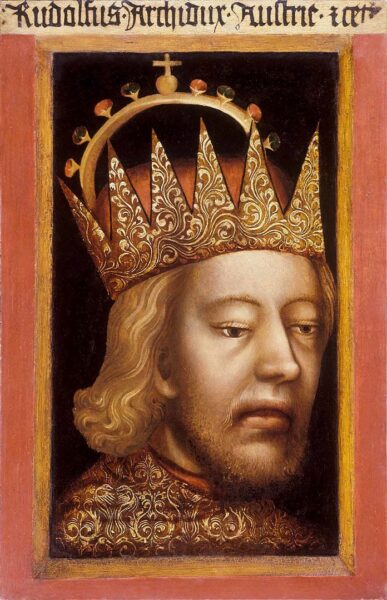

In 1365, Duke Rudolph IV, sometimes called Rudolph the Founder, established the University of Vienna – the oldest university in the German speaking world.

(Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain)

Usable stones that had survived the synagogue fire at the Judenplatz were later transported a kilometer or so west across town where they were used in constructing the University of Vienna. Thus, as a contemporary document in the University’s archives reports, “In a miraculous manner the synagogue of the old laws was transformed into a virtuous place of learning devoted to the new laws.”

The second revivification coda

I mentioned above that upon entering Judenplatz, your attention is almost immediately drawn to the stark Nameless Library that is the Judenplatz Holocaust Memorial. (In German, Mahnmal für die 65,000 ermordeten österreichischen Juden und Jüdinnen der Shoah.) Rachael Whiteread’s design was unanimously selected by an international jury with construction on the memorial to begin in 1995 and be completed by the 58th anniversary of Kristallnacht on 9 November 1996.

This plan hit a snag when excavation for the installation began and made a discovery of potential historical importance. Here’s what happened next as described on the website tracingthetribe.blogspot.com:

Less than three meters below ground level, the experts came across the stump walls and foundations of the medieval synagogue that had been destroyed in 1421. Its ground plan was clear and the archaeologists could discern that it had stood over a period of 200 years, in three distinct phases. Nearby they went down even further and found that the whole area had been used to build wooden barracks in the second century for the Roman soldiers that had occupied the area, then called Vindobona.

To the credit of the city fathers, their experts were allowed to work for three years to make a meticulous record of the three phases of the synagogue and to preserve its remains within an underground annex to what was to become the Jewish Museum of medieval Vienna. What did this medieval synagogue look like? As usual with archaeological digs, a certain amount of imagination is required, but here there were a large number of clues. The whole history of the terrible events of 1420/1 had been recorded in a Hebrew document called the Gezera of Vienna, which aimed to warn other cities of what the future might hold for them.

The earliest synagogue was a rectangular room, dated to 1236 by an Austrian penny found on the floor. The ark wall faced southeast towards Jerusalem, with an entrance to the north and a women’s room on the south with openings into the main room.

The community grew; the synagogue doubled with added columns. A unique feature was a hexagonal bima, hung with oil lamps whose remains were found. In 1350, the hall was again extended, the ark placed further east, side rooms added and the women’s annex enlarged.

Also found were:

“… a fine wooden comb (of the kind still used today to check for lice eggs), a large drinking beaker, the remains of a small toy horse and rider and a metal stylus, as used for writing on wax. The handle was in the shape of a young boy, and possibly these finds indicate the use of the rooms for a Hebrew school for youngsters. Another find was a medieval key, perhaps even the key used by the shamash (beadle) to lock up the synagogue.”

The memorial had to be moved slightly from its originally planned location and uniting the remains of the synagogue – now part of the Jewish Museum annex at Judenplatz 8 – with the Holocaust Memorial above it creates a unique connection between the Wiener Gesera and the Nazi Shoah.

That’s all for today. In tomorrow’s post, the tour turns bloody.