This would normally be the post titled “Humans arrive in…” but tracing the earliest human presence in this region is exceptionally difficult for two reasons. First, the area is little studied. Second, and perhaps the reason there has been so little study, the tropical climate isn’t suited for the preservation of ancient artifacts. An article on a subject close enough to early humans found its way into one of my internet searches, drew my attention, and sparked the thought process that led to the remainder of this post.

But first I have Tupi.

The earliest indigenous people to populate Brazil moved inland from the west coast of South America into the Amazon Rainforest before continuing their migration to the coastal area but this happened a relatively recent 2,900 years BP. Though disjointed tribally, most of these indigenes speak a common language called Tupi which is the name applied to the entire group.

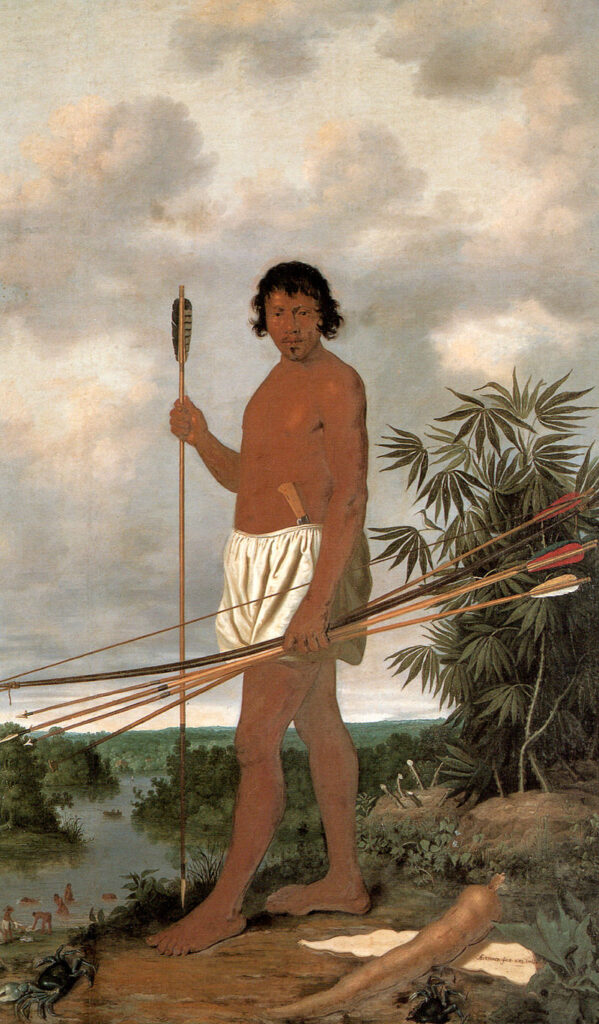

While some of the indigenous tribes were semi-nomadic subsisting on hunting, fishing, gathering, and migrant agriculture, when the Portuguese arrived in 1500, the Tupi

[Wikimedia Commons painting by Albert Eckhout – Public Domain.]

were adept agriculturalists who grew cassava, corn, sweet potatoes, beans, peanuts, tobacco, and squash.

According to the best estimates available, the Tupi population along the east coast of Brazil was at least 1,000,000 and perhaps three times that number distributed among some 200 tribes. Like so many other indigenous people in the Americas, the Tupi were decimated by the rapid spread of European diseases – mainly smallpox.

A startling discovery or was it?

This “Guanabara Bay Evidence: Did the Romans Reach the New World Before Columbus?” was the headline for the story that turned this post in a direction different from the others that have occupied this space in this series. The site is called Ancient Origins and it’s designed well enough to provide an authoritative looking experience. (It’s also an excellent site for finding unusual images.)

As I noted above, Europeans first arrived in 1500 and Portuguese navigator Pedro Alvares Cabral is generally cited as the first to guide a ship into Guanabara Bay. If the evidence presented in the Ancient Origins story proved true, it would certainly invert some of our historical notions.

In 1976 a group of lobster divers reported seeing ancient jars covered in barnacles at the bottom of the bay and it wasn’t long before one diver, Jose Roberto Teixeira, brought two of them to the surface. The ceramic jars had all the earmarks of being amphorae.

Ancient Greeks, Phoenicians, and Romans used amphorae to carry essential commodities such as water, grain, wine, or oil during sea voyages.

When more of the jars began to surface, photos began to circulate and a professor of classics from the University of Massachusetts estimated they dated to about the 3rd century CE. However, he based his analysis solely on stylistic features without having the material or any contents tested in any way. (This is a good example of how pseudoscience gets started and undermines the efforts of more serious work.) Still, this guess was enough for the Brazilian government to call in a “world renowned underwater archaeologist to determine the jars’ origin.”

Enter Robert F Marx.

Robert F Marx is a complicated character. Born in Pittsburgh, PA in 1936, Marx joined the Marine Corps at age 17 and fought in Korea. One of the pioneers of scuba diving, Marx became the Director of the USMC Diving School in Vieques, Puerto Rico. On some of his final assignments in the Corps, he embarked on a pair of cruises in the Mediterranean where he salvaged Roman, Greek, and Phoenician ships.

A self-educated marine archaeologist, Marx made over 5,000 dives, uncovered substantial volumes of ships and sunken treasure, wrote hundreds of reports and articles, and he authored 59 books on history, archaeology, shipwrecks, and exploration. He also claimed to have produced 55 television documentaries and to have appeared in more than 100.

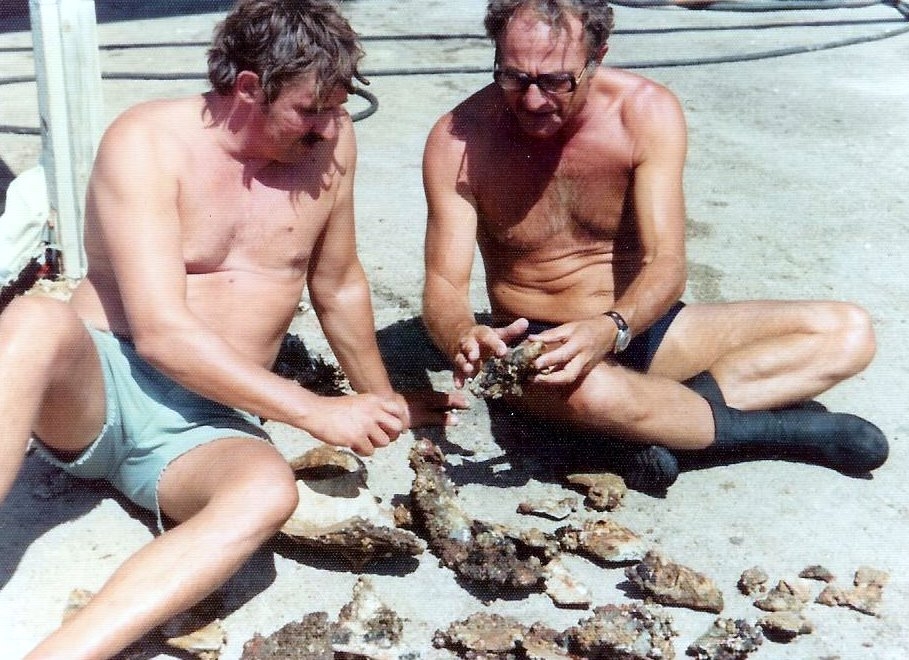

In addition to his underwater work Marx, seen here with Israeli marine archaeologist Elisha Linder,

[Photo from Wikimedia Commons BY Omri Linder and Family album – Omri Linder, CC BY-SA 3.0].

worked on the sea surface as well. In 1962, he sailed from the Canary Islands to the Bahamas in a near exact replica of La Niña thus replicating the voyage of Christopher Columbus. Later in the sixties, he captained two voyages in replicas of Viking ships to demonstrate the possibility that Nordic sailors had reached the Americas before Columbus. In one obituary, Christophe Frazier wrote, “Marx’s CV reads like an Indiana Jones movie script.”

But there was another side to Marx. He had a tendency to make overblown and often unsubstantiated claims. For example, in the early seventies, Marx so convincingly claimed he’d found the USS Monitor that Life magazine published an article about it. A few years later Gordon Watts, an underwater archaeologist for NC State University, investigated the original claim and demonstrated that the ship Marx had found was in fact the USS Oriental. Watts found the Monitor in 1977.

In 1972, Marx located the second-richest Spanish galleon lost in the Americas the Nuestra Señora de las Maravillas off the coast of the Bahamas. This eventually turned into an international incident in which the Bahamian government accused Marx of illegally plundering treasure and Marx, who once wrote, “For me adventure is a way of life,” making a countercharge of criminal activity against the Bahamian prime minister.

Still his treasure hunting success accompanied by relentless self-promotion – a man Jonathan Kirsch of the L A Times described as “a born showman” – was enough for the Brazilian government to invite him to try to settle the matter of the amphorae.

[Photo by Ad Meskins CC BY-SA 3.0.]

Somewhat unsurprisingly, it didn’t end well. While Marx’s work in Guanabara Bay failed to unearth any evidence of a Roman shipwreck, he managed to uncover some other artifacts and the Brazilians eventually barred him from their territorial waters. Marx claimed that the Brazilians banned him because they were trying to preserve the narrative that Pedro Alvares Cabral was the first European to sail those waters. The Brazilians, on the other hand, pointed to Brazilian artifacts (like gold coins) turning up at auctions for private buyers and being sold for profit. When these charges emerged, the usually loquacious Marx, who had once claimed that the Brazilians had dumped silt in the Bay to hide his discovery, turned uncharacteristically taciturn.

But what about those amphorae?

The answer is rather prosaic. In late 1959 or early 1960 Americo Santarelli, a wealthy Brazilian entrepreneur and himself an accomplished diver, traveled to Sicily. While there he visited a museum that had some ancient amphorae on display. He was so enamored by them that he commissioned a potter in Portugal to produce 16 exact replicas. But while their size and shape perfectly matched their Sicilian models, they lacked their weathered appearance.

In a final report on the Guanabara Bay discovery, Santarelli revealed that he had submerged the 16 amphorae into the bay in 1961 so that they would achieve an authentic, barnacled look. By the time of their first discovery in 1976, he had only retrieved one pair.

As for Ancient Origins, visit it if you’re entertained or amused by outlandish tales of ancient aliens and improbable pseudoscientific stories of early human history and pre-history. But I’d urge you to also treat its content as the fiction it almost certainly is.

And with this, the tour has ended. I hope you’ve found the ride not only pleasant but amusing and educational. If you have, please consider tipping your guide with a comment below.