I’ve mentioned elsewhere the challenges I face trying to distill many hours of research and reading and often tens of thousands of words of notes into a blog bite that’s not only a tenth of that size but that’s also comprehensible for people who aren’t specialists in the subject matter (including me) and still retains reasonable accuracy. Since my research isn’t formally structured, another challenge arises when I have to reconcile information of which I was previously unaware that doesn’t merely contradict but might undermine much of what preceded it. Such is the case in my reading about humanity’s pre-history in the Balkans. And this history will cover the entire Balkan peninsula and will rarely be specific to Sarajevo.

Upside down you’re turning me.

To this point whenever I’ve written about the path of hominins I’ve followed them out of Africa into Eurasia and eventually to the Americas. Yes, there was that little detour with the so-called Peking Man but the evidence seemed to resolve with African origins.

A pair of 2017 discoveries in the Balkans has raised a new series of questions. The first discovery was this fossilized tooth found in Bulgaria and dated at nearly 7 1/4 million years.

[Photo by Wolfgang Gerber – University Of Tubingen.]

The other, seen below, was a jaw discovered in Greece and dated at 7,175,000 M Y A. The age determinations were made based on analyses of the sediments surrounding the fossils. The conclusion that these fossils belonged to a previously unknown species of pre-humans was based largely on the fusion of the dental roots. This feature is characteristic of humans and their extinct relatives but not characteristic of the other great apes.

Dubbed Graecopithecus freybergi by researchers and nicknamed El Graeco, the two specimens predate the heretofore oldest specimen Sahelanthropus tchadensis – a partial cranium discovered in Northern Chad and dated to between 7 and 6 million years ago. (A femur from the same species discovered later and analyzed in 2020 determined that Sahelanthropus wasn’t bipedal a fact that might have it yield its position as a possible human ancestor.)

[Photo by Wolfgang Gerber – University Of Tubingen.]

Some researchers with an apparent Eurocentric mindset were quick to claim that these fossils and the associated findings provide evidence that the first pre-humans developed in Mediterranean Europe rather than in sub-Saharan Africa. Professor Madeleine Böhme labeled it “North Side Story” in a direct challenge to the “East Side Story” of an African origin according to the thesis of Yves Coppens. (Leonard Bernstein’s West Side Story, still stands alone.)

Others in the field have remained more skeptical. For example, Jean-Jacques Hublin, head of the Human Evolution department at the Leipzig-based Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology (MPI), who is not involved with the study said, “This is not the first time that researchers have suggested the occurrence of human like ancestors in southern Europe’s extensive fossil record.”

And in an opinion piece for The Conversation, Darren Curnoe, an associate professor at the University of New South Wales Sydney wrote, “The new claims about Graecopithecus need to be treated with a good deal of caution.” He stated that while he was open to the idea that early humans lived outside of Africa he added that relying on one feature of a small number of fossils wasn’t enough to prove El Graeco was a pre-Human. “While our place in the tree of life is now well established – chimpanzees being our closest relatives – the beginning of the human line millions of years ago continues to be shrouded in mystery.”

Professor Böhme plans to continue her research and will look for evidence in El Graeco’s diet and by investigating areas in Iran, Iraq and, possibly, Lebanon that could point to human pre-evolution outside Africa that will corroborate her theory. If she can find such evidence, it could stand the world of anthropology on its head. So stay tuned.

A tale of two caves.

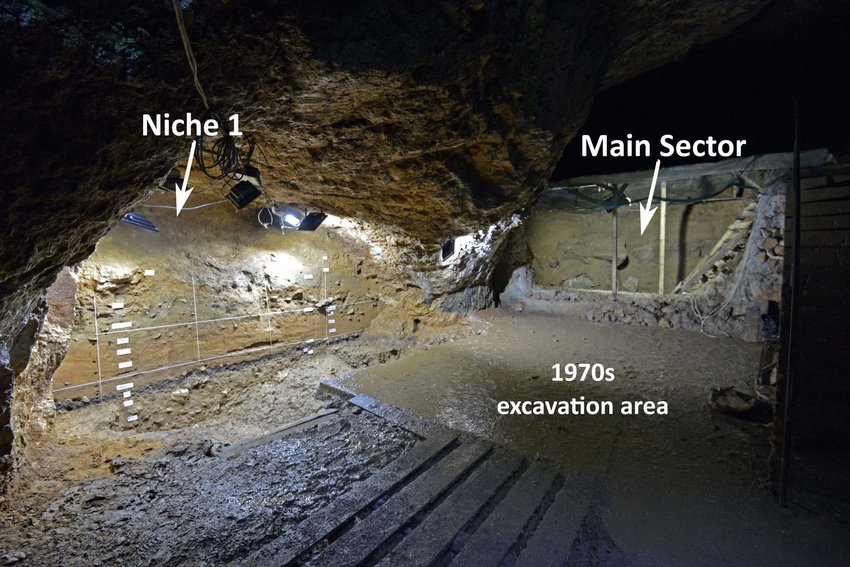

As it has through much of recorded history, the Balkan peninsula likely also plays something of an outsized role in humanity’s prehistory. And to understand it, I’ll take you briefly to two caves. Bacho Kiro cave in Bulgaria which is about 800 kilometers east of Sarajevo and Pešturina cave in Serbia that’s about halfway between the Bulgarian cave and the Bosnian capital.

[Photo of Bacho Kiro cave from Nature Ecology and Evolution.]

[Photo of Pešturina cave from Sapiens.org by Dušan Mihailović.]

Though much remains unknown about the hominin species called Neanderthals, the fossil record of their habitation in Europe is both clear and extensive. It’s also becoming ever clearer that not only did Neanderthals and H sapiens share the land, they interacted and, as we’ve seen from genetic sequencing, interbred. Perhaps they were competitors for resources as the pre-genomic model held. Perhaps they were lovers as the genomic model suggests. Perhaps over time they were both. And these two caves present some intriguing hints.

Bacho Kiro.

The first discoveries at Bacho Kiro were two partial human jaws found sometime in the 1970s but later lost. An MPI team led by Jean-Jacques Hublin returned to the cave in 2015 and began excavations with a team of Bulgarian scientists. They uncovered thousands of bone fragments, stone and bone tools, beads and pendants, and a human molar. Researchers extracted DNA from four fragments and the tooth that all identified as human. They also found that the mitochondrial sequences belonged to H sapiens.

In another lab at MPI, radiocarbon dating specialist Helen Fewlass and her colleagues directly dated collagen from 95 bones dating the human bones and artifacts as being from 43,650 to 45,820 years ago.

[Photo of tools from Researchgate by Tsenka Tsanova.]

Animal bones cut or modified by people suggested they were in the cave “probably beginning from 46,940” years ago, Fewlass says.

At this time, Neanderthals were still the dominant hominin in Europe but the climate had begun warming and H sapiens began migrating from western Asia bringing with them the Initial Upper Paleolithic (IUP) toolkit. Neanderthals had long occupied the region and left stone tools in the same cave more than 50,000 years BP.

Neanderthal technology is characterized as Mousterian and its stone shaping techniques are generally considered more primitive than those used in the IUP and which eventually gave rise to the period and style called Aurignacian. One of the elements that makes the findings in Bacho Kiro particularly intriguing is the discovery throughout Europe of transitional artifacts coupled with the fact that over a period of several thousand years Neanderthals were using some of these more advanced techniques. This has ignited or perhaps reignited debate about how Neanderthals and moderns may have influenced each other. In the photo below, the artifacts on the left are jewelry and bone tools from Bacho Kiro Cave in Bulgaria, created by Homo sapiens (modern humans) about 45,000 years ago. The artifacts on the right are slightly more recent jewelry and bone tools created by Neanderthals and found in Grotte du Renne in France.

[Photo from Discover Magazine Rosen Spasov and Geoff Smith, MPI-EVA Leipzig CC-BY-SA 2.0.]

So, as always, stay tuned.

Pešturina.

Setting out westward from Bacho Kiro we continue our journey toward Sarajevo. Roughly 400 kilometers through what we might call the crossroads of Europe and Asia we reach Pešturina Cave a spot about 20 km from the city of Niš in southeast Serbia. It’s one of several important migration corridors for both animals and people that intersect throughout the Balkan Peninsula. The Danube River, for example, cut paths through mountain ranges that not only provided convenient routes with an ample source of water but also carved many of the same valleys the Neanderthals called home.

Facing the great floodplain of the Nišava River in the side of Jelašnica Gorge, along one of the migratory paths is where we find Pešturina Cave.

[Photo from Wikipedia By Geograf208 Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0.]

Although paleoanthropologists have yet to find modern human and Neanderthal skeletons together at the same site, there’s good evidence that both hominin species occupied this cave albeit likely at different times. A Neanderthal tooth dated to 100,000 years ago was found there in 2015. The cave also has abundant tools manufactured in the Mousterian stone tool tradition.

The presence of stone tools made using IUP techniques indicates that modern humans also inhabited this cave thereby making Pešturina one of the very few sites in Serbia where both groups had clearly lived in the same place. Will further excavations reveal evidence of cohabitation or shed some light on the frequency with which the two hominins mated? Only time will tell. So, as I seem to write frequently, stay tuned.