Paleoindian life – a brief summary.

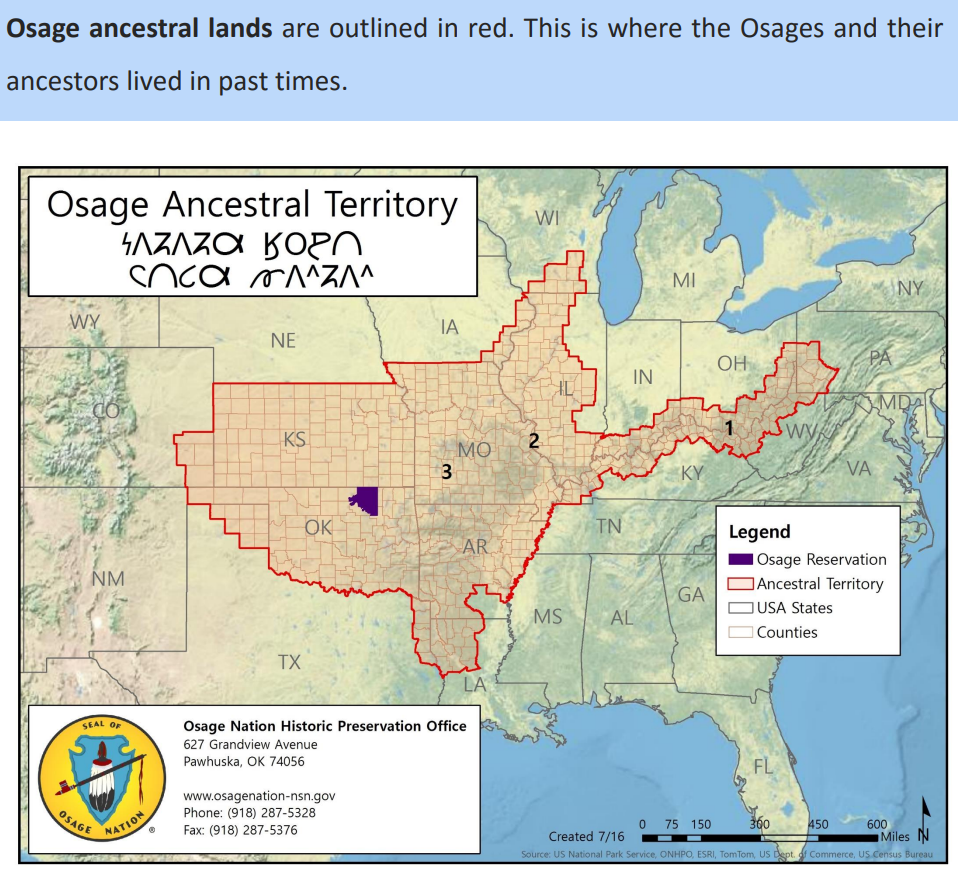

By now, regular readers of this blog should have some idea of the time and manner in which the earliest humans arrived on the American continents from a post such as this one so I won’t reiterate those lessons. Further, most of this post will focus on the tribe we know today as the Osage because the borders of their traditional territory reached to the Missouri River in the north, the Arkansas River to the south, and the Mississippi River to the east.

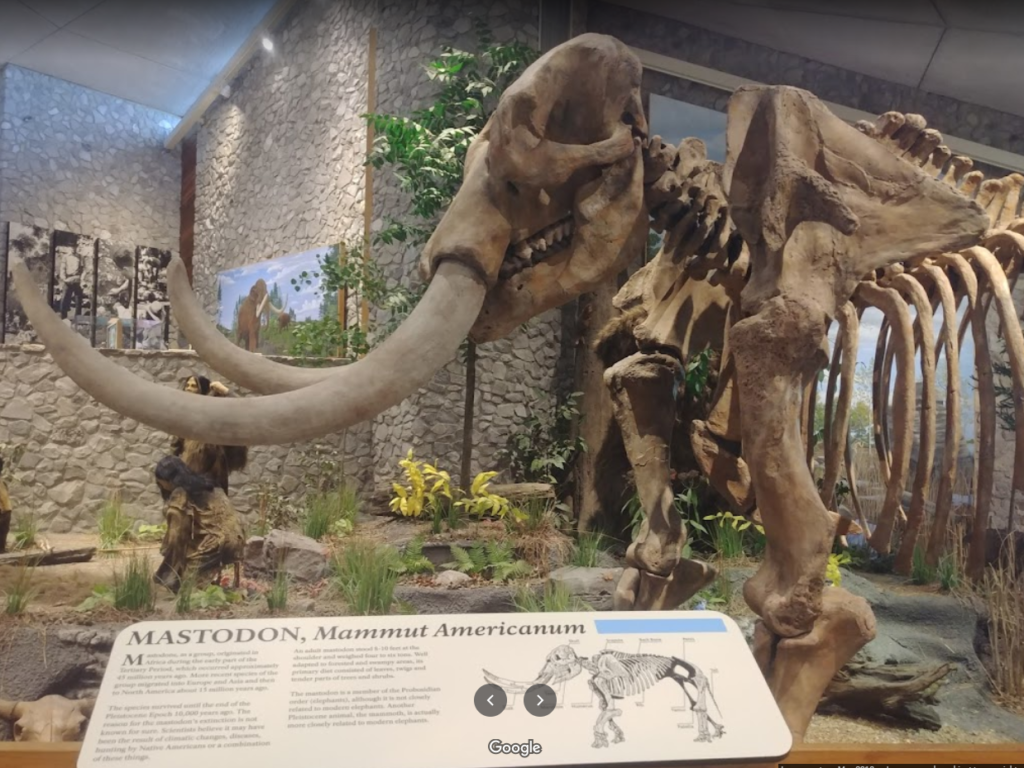

There has been a human presence in and around the area’s major rivers (Missouri and Mississippi) for at least 12,000 years. Strong evidence found at the Mastodon State Historic site just 25 miles south of Saint Louis indicates that these Paleoindians used a fluted point hunting tool similar to the ones discovered in Clovis to hunt great beasts like the one in the photo. Together with most other megafauna (larger than 100 pounds or 45 kg) of the Pleistocene, mastodons

would become extinct within 1,500 years likely due to a combination of hunting pressure and climate changes.

By 7,000 years BP, the climate had turned both warmer and drier allowing the prairies to expand into previously forested areas. With evidence drawn by tracing the changes in the shape and functionality of the tools used by these ancients, scientists have concluded that plants became an important part of the diet and smaller animals such as rabbits, birds, and fish replaced deer as the principal sources of protein.

Over the next several millennia, the climate would change again and forests would reclaim some of the land that had become prairie. This period, spanning from 5,000 years BP to 3,000 years BP is generally classified as the Late Archaic. During this time the first pottery vessels appear and it marks the first documented use of domesticated plants: squash (Cucurbita pepo) and bottle gourd (Lagenaria siceraria).

Socially, this time saw the first large village settlements and burial rituals. Missouri’s oldest documented burial mound (Hatten Mound) is in Monroe County 40 miles west of Hannibal.

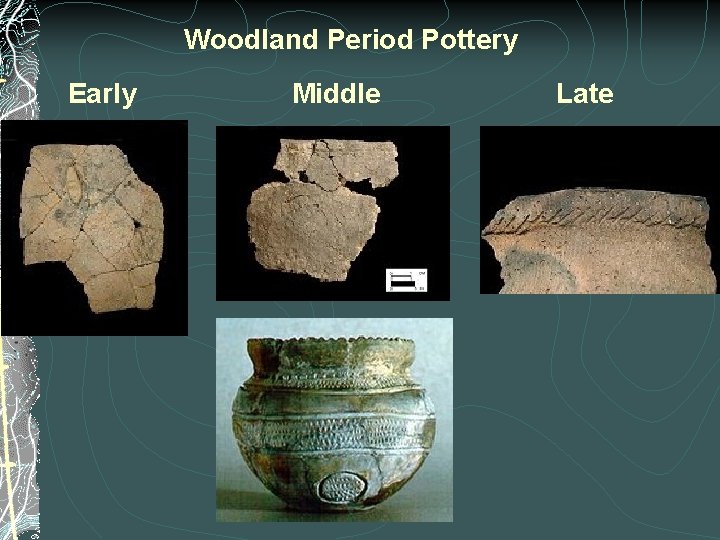

The Woodland Period which spans the time from 1,000 BCE to 900 CE saw widespread technological and social changes spread across the entire Midwest. Some of the pottery produced during this period is decorated with designs created by cord-wrapped impressions, small hollow-reed impressions, or incised lines.

[Image from slidetodoc.]

Small clay figurines representing human and animal forms also appear in the middle of this period.

The period known as the Mississippian began about 900CE and lasted for about eight centuries until the arrival of the first Europeans. Tribes are becoming well established and there’s evidence of the first large permanent villages. Here, populations now rely upon corn cultivation as a major component of their diet. Not only is there evidence of the fortification of these villages but the towns themselves feature temple mounds, plazas, and astronomical observatories.

In the 1300s, we see the rise of the mound builders civilization which spread to both sides of the Mississippi. The largest mound complex is in Cahokia, Illinois a few miles east of Saint Louis. Those of you who followed my journey along the Great River Road might recall the growing fascination I developed with the various mound builder sites I encountered along the way.

What’s in a name?

Sometime in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the Mississippian culture began to decline and disperse and two indigenous groups – each with its own traditions and technologies came to dominate the area. I’ll begin with a brief discussion of the tribe that gave the state and the river its name – the Niutachi. If you think this looks like it sounds nothing like Missouri, you’re right. Missouri is a European corruption of a tribal word, it’s simply not one that belonged to this particular tribe. They lived mainly north and west of the Missouri River which they called Pekitanoui but possibly had settlements as far south and east as the confluence of the Missouri and Mississippi rivers.

[Portrait from Smithsonian NMAA – George Catlin 1832 Háw-che-ke-súg-ga Chief of the Missouri Tribe.]

Here’s the story of Missouri: Led by guides from the Peoria tribe, who likely would have called these local inhabitants Wemihsoori (People of the Wooden Canoes), French explorers of the late seventeenth century noted the tribe’s name as “Ouemessourit” (in French the final ‘t’ is silent). They then drew maps attaching this appellation to the land and the river they lived beside. Eventually, the process of elision reduced the pronunciation to Missouri.

A different pair of processes nearly obliterated the tribe. The first came from the uncounted losses inflicted by the same European diseases – smallpox, measles, influenza, and cholera – that afflicted most Native American tribes after their early encounters with Europeans that literally decimated the Missouri reducing its number from an estimated 10,000 in 1700 to barely 1,000 in less than a century. The second was an ongoing conflict with the Sac and Fox Indians who struck a near fatal blow sometime between 1790 and 1800 in a raid that killed an estimated 600 of the small surviving number. A handful survive today having been absorbed by the Otoe. These few live today in Red Rock, Oklahoma as the Otoe-Missouria.

Osage can you see.

The second indigenous group called themselves Wazhazhe meaning Children of the Middle Waters. Once again, French explorers misheard and mispronounced it so it comes to us today as Osage.

The Osage began life as one of the Dhegiha Siouan tribes in the Ohio River valley. Sometime in the Middle Woodland period (200-400 CE) the Dhegiha began its migration down the Ohio River valley to the confluence of the Mississippi and Ohio rivers. During the Late Woodland period, most of the Dhegiha tribes migrated up the central Mississippi River valley eventually settling in the Saint Louis area. They also traveled westward from the valley following the various river drainages into the interior of what is now Missouri. Between 900 and 1000, large groups of the Dhegiha Siouan tribes focused their settlement strategy on both sides of the Mississippi in the Cahokia/Saint Louis area while the tribes who would later become the Omaha and Ponca continued a westward migration.

[Map from Osage Nation.]

The Osage remained in the Saint Louis area until 1300 at which time they, too, shifted their settlement pattern and moved westward. They settled mainly within the central and western portions of present day Missouri and from the early 14th century large groups of the Osage were located along the Missouri and Osage rivers.

Although continuing to expand their territorial reach the Osage had, by this time, largely abandoned their nomadic ways and were settling into more permanent villages. These villages were divided into two main clan groups: the zi-shu, or Sky People, lived on the north side of the village and the Hunkah, or Earth People, lived on the south. A wide street running east to west to follow the path of the sun separated the two clan groups as did their function within the tribe.

[Image from Missouri Life.]

The Sky People and their chief oversaw civil concerns while the Earth People and their chief acted as the military. Each chief’s lodge sat in the middle of the street and each was an acknowledged tribal leader. The Osage lived within a rigid, tradition-based system of self-government. However, for moral and spiritual governance and for adherence to tribal traditions, the chiefs and the rest of the tribe deferred to the Ne ke a shin ka (the “Little Old Men”), an elite body of elder sages.

In their book The Imperial Osages, Gilbert Din and A P Nasatir wrote,

The territory from the Great Bend of the Missouri south to the waters of the Arkansas and east toward the Mississippi was the country of the Osages for several centuries before the advent of the Europeans. Here was their hunting ground. Over the high plateaux of the Ozarks and in the deep valleys cut through the plateaux by water they reigned as masters.

And so they would reign for centuries. Then, in 1673, the first Europeans, Father Jacques Marquette and Louis Joliet, during their voyage down the Mississippi River reached the land that would later become Missouri. On 15 February 1764 Pierre Laclede and Rene August Chouteau established a fur trading post on high ground about 15 miles south of the confluence of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers. That trading post became the city of Saint Louis.

Between 1808 and 1839, the Osage signed seven treaties with the United States. The first treaty signed at Fort Clark in 1808 forced the Osage Nation to cede 52,500,000 acres of land in Arkansas and Missouri. For this, the Osage received $1,200 in cash and $1,500 in merchandise. Ten years later a second treaty ceded another 1,800,000 acres in Arkansas and Oklahoma. For this, the Osage received no compensation. A third treaty, signed in 1825, wrested all remaining tribal land and moved the Osage to the small reservation along the Kansas border seen above. In total, the American government acquired 96,800,000 acres in the three treaties at a cost of $166,000.